Tajikistan, Central Asia’s poorest country, recently got some very modern equipment. In 2017, over 600 high-tech diagnostic laboratories — capable of performing DNA tests, genetic analyses, and other procedures — were installed at medical centers across the country. The labs were introduced as part of a partnership between the government and a private company called Faroz — and this was neither the first nor the last time the firm has enjoyed such a privileged deal.

In fact, Tajiks come across this name frequently in their daily lives. Faroz is engaged in a wide range of fields, including oil and gas, mining, customs terminals, driving schools, spas, a winter sports complex, a bank, and other private businesses.

A slick promotional video associates the company’s success with that of Tajikistan: “Faroz. A national company for the good of the nation.” And this success is often publicly applauded by President Emomali Rahmon, who has ruled the country for nearly 30 years. Whenever Faroz unveils a new project, Rahmon can be counted on to cut a ribbon, offer some kind words, or strike a photogenic pose.

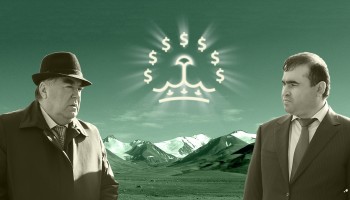

But why would Tajikistan’s unchallenged ruler show such high-level interest in the activities of a private company? As it turns out, there’s a good reason: It’s all in the family.

The key figure is Shamsullo Sakhibov, who is married to one of the president’s daughters. As Rahmon’s son-in-law, the 36-year-old Sakhibov occupies a powerful position in a country ruled by a small, insular elite.

Edward Lemon, a Tajikistan expert at the Harriman Institute at Columbia University, explains that the country’s economy is dominated by businessmen linked to the presidential family who use their control over government agencies to “skew the market in their favor.”

“This corruption ... pervades every level of the society and the economy,” Lemon says.

Sakhibov — the owner of Faroz — is no exception.

“If Sakhibov wasn’t part of the system by being married into the [Rahmon] family, Faroz … would probably be targeted itself,” Lemon explains.

But he is part of the system. And this has allowed Sakhibov to lead Faroz to ever-greater heights. An investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) reveals that its growth was made possible, in large part, because the government created opportunities for it to flourish and ensured that none of its competitors would pose much of a threat. The state has been used for the good of the company, not the other way around.

Reporters reached out to Faroz, Sakhibov, and the presidential administration with requests for comment, but received no responses.

Building an Empire

On paper, Sakhibov has been Faroz’s sole owner as of this January. That’s when he returned from the United Kingdom, where he worked for years as Tajikistan’s trade representative.

Prior to that, records show the company as being registered to his father Makhmadullo and his brother Zainullo. But reporters have found that, in fact, the company has been under his control ever since he wrested it away from his partner in 2012. (See: A Murder in Istanbul)

When Faroz was first established in 2002, its predominant business activity was the import of liquified gas. That, as well as the oil trade — it has a pipeline to Afghanistan — still forms an important part of its business. It operates a network of 50 stations that sell gas and petroleum products on the retail market.

But Faroz is not just another player in the market — it’s become a dominant force. In 2013, the company established its own “Association of Oil and Liquefied Gas Importers,” which, according to the business registry, aimed at lobbying the “interests of oil importers.” While the association doesn’t even have its own website, its influence on the market is not to be underestimated. Two industry insiders who spoke on condition of anonymity told reporters that would-be importers need to be in its good graces to obtain an import license or get permission to install their own fuel tanks.

But these days, Faroz has far broader ambitions. In fact, it has grown so big that it’s difficult to name an industry where it’s not present.

Comprising more than 40 companies, it does business in trucking, pharmaceuticals, information technology, mining, banking, steel, and the leisure and tourism industry.

And it can attribute much of its success to outside help. A look into its recent business history reveals that the government has assisted the company by passing favorable laws, putting pressure on competitors, and selling it public assets at bargain prices. Sometimes, the state would go so far as to leave Faroz as the only player in the field.

OCCRP has investigated the major industries in which Faroz has gained an upper hand — and the government machinations that lay behind them. Click below to read about: