In most countries, international customs terminals are run by the state. But in Tajikistan, a private company with special connections boasts a network of 10 so-called international terminals — which house all the state agencies needed to perform clearance procedures for incoming vehicles — on the Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Afghan, and Chinese borders. The country has four other terminals run by other operators.

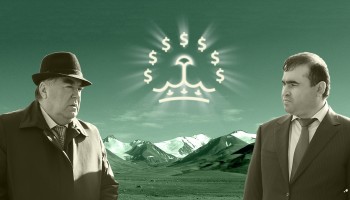

Faroz came to own its largest terminal through a special law that was promoted by the president himself.

In April 2011, President Rahmon appeared in parliament with a strong complaint. He lamented Tajikistan’s dependence on imports and called for a boost in the domestic production of consumer goods. To solve the problem, in part by attracting foreign investment, Rahmon ordered the government to draft a law on public-private partnerships.

A year and a half later, he signed the new law into effect.

It provides for several ways for public-private partnerships to come into being — whether initiated by the government or by the prospective private partner themselves. As part of the deal, the state is to “provide its private partner with a plot of land” — and there is no mention of any payment. If needed, the state can also help the private partner obtain land plots held by third parties.

When Rahmon praised the law and its results two and a half years later, he did so at the opening of a logistics and customs terminal near Dushanbe that was built by Faroz, his son-in-law’s company, making it a strange example of a public-private partnership within one family.

Out of six such projects then active in Tajikistan, this was the only one in which the private partner was Tajik.

Built for over US$ 20 million, the new complex, build in an old truck depot, consists of a customs terminal, a driving school, a hotel, a road police unit, and a number of inspection agencies.

During the unveiling ceremony, Rahmon ordered Faroz’s “patriotic businessmen” to build more “world class” terminals like the one he had just opened.