One of the most unusual industries Faroz has come to dominate involves the export of asafetida, the gum resin of the ferula plant.

Asafetida — infamous for its strong, repugnant smell and bitter taste — is often called the “devil’s dung” or “stinking gum.” In India and Pakistan, it’s highly regarded as a condiment, more widely known as hing, that is used in lentil and eggplant dishes. In traditional medicine, it’s a remedy for constipation, flatulence, and bloating.

To produce asafetida, the massive taproots of the ferula plant are scored to release a milky resinous juice that dries slowly on the root. This is scraped off and collected.

One kilogram of the raw resin, which a skillful collector can obtain from one or two plants, can fetch prices of up to US$ 100 abroad — three times the average monthly pension in Tajikistan. For a time, harvesting and selling asafetida was a way for many poor Tajiks to earn a living.

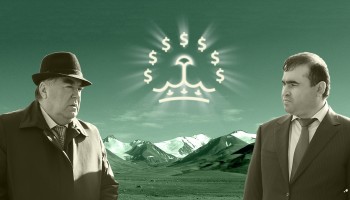

But it didn’t take long before even this natural resource drew the attention of President Emomali Rahmon.

In September 2008, Rahmon issued a decree “categorically prohibiting” the collection and export of ferula gum resin. Less than three months later, Tajikistan would criminalize the harvesting of ferula to nearly the same extent as the production, storage, or sale of small quantities of heroin.

At the same time, the president ordered the government to look into the possibility of processing the resin domestically.

But in August 2009, Rahmon reversed his decision, introducing a system of quotas for the harvesting of raw asafetida (though its export was still forbidden).

Notably, the quotas were to be issued only to companies with their own processing and production facilities in Tajikistan. And one company — Faroz — happened to be opening such a facility in the Khatlon province, 110 kilometers south of Dushanbe. The facility was announced just after Rahmon’s second decree, and Faroz got the only license.

The company’s press release noted that, while the facility could currently produce and export two ferula-derived products, its capacity would continue to expand. “Laboratory work is already underway to produce several more types of medicinal products and biologically active additives from this unique plant with its medicinal properties,” it read.

Faroz was just getting started.

In 2015, the government announced the approval of a second ferula harvesting license for a company called Minu Farm. According to officials, it would have the right to process 100 tons of ferula resin, 40 tons more than Faroz’s quota.

According to the Tajik business registry, Minu Pharm was established in March 2012 and is owned by a man named Faizullo Shirinov. It appears Shirinov was doing double duty: About year later, a story by Radio Free Europe’s Tajik service quoted him as a department head in charge of Faroz’s ferula business. And in March 2015, Faroz’s corporate Facebook page posted a video about Minu Pharm, presenting it as part of its pharmaceutical business.

As with most of Faroz’s other enterprises, President Rahmon found time in his busy schedule to inspect Minu Pharm’s operations. After his 2013 visit, his office issued a press statement praising the company’s exports and noting its production of medicine from the venom of poisonous snakes.

The original reasoning for President Rahmon’s ban of the export of raw asafetida was to encourage its domestic processing. Having thus cleared the market for Faroz, it emerges that, nevertheless, the export of raw asafetida continues. According to export data, Tajikistan exported 6.6 tons of the resin to India in 2015-2016. Since Faroz and Minu Farm are the only companies licensed to harvest it, this raises the question of whether these companies are enjoying an exception from the law that has banned this business for everyone else.

Meanwhile, Faroz seems to be expanding its pharmaceutical business. In July 2017, the company launched a network of 600 medical labs in Tajikistan’s health clinics. With this many locations, the company is poised to become a dominant player on the market.