The question of who controls a sovereign wealth fund with over $68 billion in assets should be straightforward. In Libya, it has been anything but.

Under former dictator Muammar Gaddafi, state institutions were used as conduits for graft, embezzlement, and money laundering on a monumental scale. Billions of dollars in oil wealth flowed into doomed investments, vanity projects, and the pockets of well-connected elites.

The 2011 uprising that toppled Gaddafi raised hopes that reform was finally at hand. Instead, the country was plunged into a complex civil war that pitted rival ideological, tribal, and regional factions against one another. The conflict set off a vicious battle for control over Libya’s wealth, waged not just with assault rifles and rocket launchers on the ground, but with high-end lawyers in courts as far away as London.

Over time, the country’s political divisions were mirrored in its key institutions, with competing versions of the central bank, national oil company, and parliament established at different times, backed by different political leaders, operating from different parts of the country. A maddeningly complex situation arose whereby rival leaders initiated separate legal actions, appointed officials, and cut deals, sometimes in direct contradiction with one another.

This threw a spanner into efforts to reclaim billions of dollars of assets frozen around the world and redress Gaddafi-era wrongdoing, as different factions argued that they were the rightful representatives of Libyan state institutions.

The factional complexity also created new opportunities for individuals to pursue personal agendas while claiming to work on behalf of official institutions, and helped people accused of looting government funds under Gaddafi avoid justice.

One of the main disputes centered around the country’s sovereign wealth fund, the Libyan Investment Authority, known as the LIA. Set up in 2006, the fund eventually developed a portfolio valued at over $68 billion. It also came to encompass some 550 subsidiaries — with deliberately opaque structures that a U.N. Panel of Experts later said were designed “to facilitate the laundering of funds embezzled from the State to personal assets abroad.”

After Gaddafi was toppled and killed, Libya’s new leadership appointed Mohsen Derregia, a former accounting and finance lecturer at the University of Nottingham, as the head of the LIA. But he lasted just under a year before he was replaced by a former banker, Abdulmagid Breish.

Breish was then pushed out about a year later under Libya’s controversial “political isolation law,” which banned Gaddafi-era officials from holding senior positions, a decision that would lay the groundwork for future quarrels over the fund’s control.

At the time, the episode was a sideshow to a broader drama playing out as Libya spiraled back into civil war. In June 2014, the same month Breish left his job, parliamentary elections were held to replace the transitional government. Islamist candidates fared poorly, and two months later, Islamist militias stormed Tripoli, forcing the newly elected lawmakers to flee the capital.

Parliament re-established itself in the city of Tobruk, over 600 miles to the east. A rival government was then set up in Tripoli.

The de facto division of the country threw Libya’s state institutions into “administrative chaos,” Chatham House researcher Tim Eaton wrote in a detailed 2021 report on the subject.

“The absence of both a unified and universally recognised executive and legislative [branch] led to the emergence of parallel leaderships of state institutions and undermined any checks and balances that did exist in Libya’s governance,” he wrote. “The LIA was no exception.”

Divisions Come to the LIA

In October 2014, the Tobruk-based authorities appointed a new LIA head, Hassan Bouhadi, a business executive who had worked for multinational giants such as Bechtel and BASF. Due to the ongoing fighting, Bouhadi decided to move the LIA’s headquarters from Tripoli to Malta.

But the disunity affecting Libya as a whole would not spare the fund.

In April 2015, a court in Tripoli overturned the ruling that had forced Breish to relinquish his position, leading him to claim that he had been rightfully reinstated. He set up shop in Tripoli, meaning there were now two rival LIA offices: one in Tripoli under Breish and another in Malta under Bouhadi.

The split had immediate ramifications for Libya’s efforts to redress Gaddafi-era grievances.

Before Breish was removed, the LIA had filed lawsuits against Goldman Sachs and Société Général in the U.K., seeking to reclaim over $3 billion invested in controversial Gaddafi-era deals. The split led to a legal tangle over who had the right to represent the fund and continue the suits.

The LIA eventually lost the Goldman Sachs suit and settled with Société Général. But the leadership dispute was still far from resolved. As Libya’s civil war dragged on, different factions aligned, realigned, and traded control on the ground, with reverberations in legal claims to assets across the world.

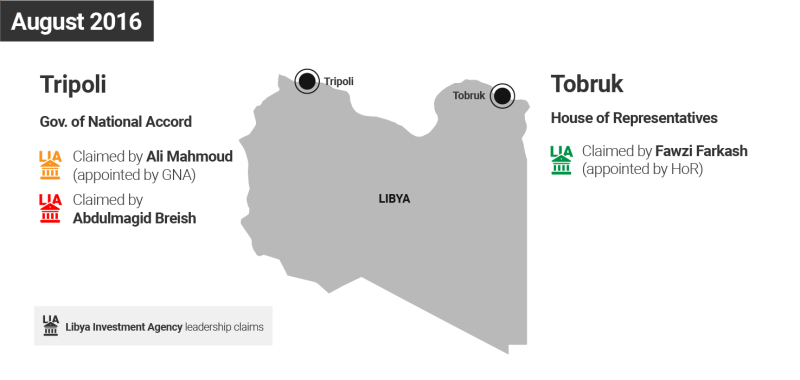

In December 2015, a United Nations-brokered power-sharing agreement produced a “Government of National Accord,” widely known as the GNA. The deal was meant to unite east and west, but the Tobruk-based parliament soon rejected the new government and continued to operate independently.

Under pressure from the ongoing conflict, Bouhadi stepped down as head of the LIA in August 2016. The GNA, now based in Tripoli, moved to appoint a replacement named Ali Mahmoud. The eastern authorities, meanwhile, appointed a completely different replacement of their own.

In some ways this signaled the end of the Malta-Tripoli division. But rather than simplify matters, it gave way to an even more bewildering situation. Three people were now claiming to head the LIA: Breish and Mahmoud in Tripoli, and another rival in the east.

Matters on the ground were no clearer. As fighting continued, Breish and Mahmoud actually physically exchanged places occupying the LIA’s headquarters in Tripoli for a period in 2016 and 2017.

By May 2020, four different people were claiming to head the LIA.

A court decision that month in the U.K. was the closest thing to a resolution of the dispute. The case, initiated by Bouhadi before his resignation, had been underway for about five years before the court finally ruled in favor of Mahmoud and the GNA, explicitly rejecting Breish and the eastern-backed claimant.

Subsidiary Chaos

These disputes got particularly complicated at the level of LIA’s many subsidiaries. The subsidiaries often aligned with different factions, were subject to their own leadership disputes, and operated more or less independently. Even more confusingly, the divisions among the subsidiaries did not always map cleanly onto the already convoluted LIA dispute.

One example, illuminated by OCCRP’s reporting, shows how messy things could get in practice.

In late 2014, an LIA subsidiary known as the Libya Africa Investment Portfolio, or LAIP, had its offices in Tripoli overrun by a militia from Misrata. Its managing director, Ahmed Kashadah, moved the LAIP offices to Malta, where he worked within the LIA structure controlled by Bouhadi.

Kashadah then had to contend with a challenge, waged in Maltese courts, by Derregia, the LIA’s overall first post-Gaddafi head, who was now also claiming to run the LAIP — whose assets included gas stations, phone operators, and real estate across Africa — from Tripoli.

Meanwhile, a related leadership dispute played out yet another rung down the ownership ladder. LAIP owned a company called the Libyan African Investment Company, or LAICO, which owned luxury hotels and other property across Africa, and thus continued to generate revenue.

A man named Ibrahim El-Danfour had been appointed LAICO’s general manager in 2014, at a time when the LIA was still relatively united. But in November 2015, the version of LAICO affiliated with Kashadah’s LAIP, now in Malta, tried to remove Danfour from his position and appoint a new general manager.

Danfour refused to vacate his post, dismissed the order as illegitimate, and continued to present himself as LAICO’s general manager. (Speaking to OCCRP, Danfour acknowledged that his standing as general manager had been “challenged in the wake of the political and administrative divisions that took place in Libya, which impacted many of Libya’s sovereign wealth fund’s vehicles,” but said he had remained the company’s legitimate head throughout.)

“The absence of both a unified and universally recognised executive and legislative [branch] led to the emergence of parallel leaderships of state institutions and undermined any checks and balances that did exist in Libya’s governance. The LIA was no exception.”

Tim Eaton, Researcher, Chatham House

The two sides then waged a protracted legal battle, in Libyan courts and abroad, arguing against each other’s legitimacy as they sought to secure control over various assets in countries including Tunisia, Zambia, and Belgium.

Kashadah died in November 2017. Soon after, Danfour expressed recognition for the new LIA leadership under Ali Mahmoud and the GNA. By that point, the United Nations had recognized the GNA as Libya’s government, and a few years later the U.K. court judged the LIA operating under the GNA to be the rightful LIA. (Danfour also told OCCRP the dispute had been resolved in late 2017.)

But despite this apparent recognition of the “real” LIA, matters have remained complicated.

Political leaders in eastern Libya who rejected the GNA had since allied with a renegade general, Khalifa Heftar, who mounted a military challenge against the internationally recognized government, culminating with a failed attempt to seize Tripoli launched in April 2019.

Authorities in the east also put forward their own head of LAICO, Mohamed Kahloul.

Starting late that year, Kahloul began claiming to head the company, and once again contesting claims to LAICO’s assets abroad.

In a letter related to an unresolved legal dispute over LAICO assets in Belgium, he demanded that they be “kept safe from being looted by any unauthorized representatives” of LAICO or LAIP.