Andras Horvath’s living room is overstuffed with randomly piled papers and other clutter. But anyone who knows his story will key in immediately to just one item: the green folder next to the sofa.

Could that be the one? The famous green folder he waved during anti-corruption protests four years ago, when tens of thousands Hungarians roared their anger at the government?

Turns out that’s not it. But Horvath will forever be remembered by his folder, which contained evidence of massive tax fraud perpetrated by some of the country’s biggest companies -- and of the government’s complicity.

That folder almost ruined his life.

Andras Horvath had been working as a tax inspector for 11 years when, in 2011, he realized that something wasn’t right.

Some big companies in Hungary were stealing millions from the tax authorities through a complex scheme known as the carousel fraud that cost the budget $4.5 billion per year.

The scheme involves misusing an EU regulation which allows a company to import goods from another member country without paying VAT. By reselling the goods domestically multiple times and claiming VAT refunds from the government, the scheme’s operators can defraud tax authorities to the tune of millions.

And it’s not just Hungary. The scheme is Europe-wide and, according to the BBC, costs European taxpayers almost US$ 229 billion, or twice the EU’s annual budget, per year.

It sounds confusing, but uncovering such schemes was Horvath’s specialty. He notified his supervisors, but though they seemed supportive, they did nothing.

In October 2011, Horvath shared his findings with the management of the country’s tax authority, the National Tax and Customs Administration. When he finished his presentation, the silence in the room was deafening.

“It felt like everything froze around me,” Horvath remembers. “I should have seen what was coming, but I didn’t.”

What followed made Horvath realize that everything he had always believed was false. Catching criminals red-handed wasn’t enough. Hungary wasn’t the country he thought it was. And his employer, the tax authority, was systematically letting big companies get away with it.

“They were untouchable,” he says. “And I wasn’t the only one who realized this. Everyone who worked in my field at [the tax authority] knew this,” Horvath says. But he was the one who said it.

Changing tactics

For the next two years, Horvath kept his mouth shut and his profile low, doing his job and pretending everything was business as usual.

But after work, he would sit in front of his computer in the living room of his suburban home near Budapest and collect evidence against those who were stealing from the nation’s wallet and those who were helping them.

Sometimes he sat there day and night, putting the jigsaw puzzle together while neglecting his clueless family and putting a strain on his marriage.

Horvath was still hoping that once he had the whole picture, someone in Hungary’s ruling circles would listen and perhaps do the right thing.

Throughout 2012 and 2013, he repeatedly sent letters to high officials through the mail and through intermediaries. He even wrote to Janos Lazar and Antal Rogan, two ministers close to Prime Minister Viktor Orban, describing in detail what he found.

Then he wanted. Still nothing.

By the end of 2013, he felt that he had done everything he could -- except for one thing.

He would address the victims -- the Hungarian people -- directly, telling them who was stealing from them and how much. Then he would let them do what he couldn’t.

That November he submitted a report to Hungary’s Chief Prosecutor, backing his statements with documentary proof. According to Horváth’s estimates, the sum of the illegally evaded and reimbursed VAT equaled 5 to 6 percent of the country’s GDP.

Then Horvath put some of the evidence into a green folder and laid out his claims to the public at a press conference. The sums he named were shocking. The tax agency had deliberately let big companies steal $4.5 billion annually.

Hungarians fumed. Soon they took their anger to the streets for days of demonstration, demanding an end to the plunder and jail for the thieves. Horvath addressed the crowd from a stage, waving his green folder.

It looked like it might work.

“Naively, I thought that if I have factual proof of a case that concerns such an incredible amount of public money, if I am brave enough to go public with a story, then no government can look the other way,” he says.

Such a huge scandal, which exposed systematic corruption, would have had serious political consequences in a healthy democracy, he thought. Leaders would have to resign.

“Obviously, this did not happen,” says Horvath with a big sigh.

Instead, at 7:30 in the morning a few days before Christmas, four detectives appeared at his front door. They searched the house and confiscated the green folder, Horvath’s hard drive, and a notebook where he kept the names and phone numbers of journalists, politicians, and lawyers he was in touch with.

Authorities accused him of mishandling personal data and launched an investigation against him instead of the people he had exposed. Police took his fingerprints and threatened him with jail. It took almost four years for authorities to drop the charges as unfounded.

For Horvath, the worst part of the ordeal was what it did to his family. Until the day he went public, nobody at home knew what he was cooking up. His wife was furious. Not only had he exposed his family to the pressure of the scandal, but he left them partially without income.

“I know that it’s impossible to completely forgive this,” he says. “But nobody in my family turned away from me.”

The moment Horvath stood in front of cameras with his green folder, his career at the tax authority was over. For the next three years, he was unable to get a job. Apparently, he is still blacklisted at the public sector. Even the municipalities led by opposition politicians refused to hire him.

In the second half of 2016, he was finally hired by an opposition party as an analyst. He serves there as a watchdog, looking out for more tax avoiders. “I can continue my work that focuses on cleaning up that sector,” he says with a smile.

Despite everything, Horvath has no regrets. Although the carousel is still spinning, the most corrupt managers at the tax authority were fired or sidelined. Ernst & Young confirmed the fraud in a study and the government lowered the VAT for some food products to lower incentives for big companies to ride the carousel.

The street protests eventually fizzled out, but the ruling party’s popularity plunged and stayed down for months.

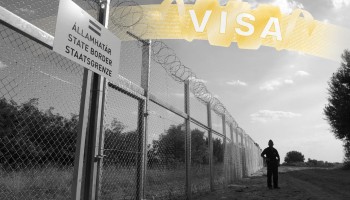

Even the US government took notice of the scandal, introducing a visa ban against six Hungarians, including the then-chief of the tax authority. The US embassy in Budapest cited Horvath’s green folder as one piece of evidence.

Horvath says that, when he decided to stand up, he was so outraged that he didn’t really think about the consequences.

“If someone is born with a sense of justice,” he says, ”one day the levee breaks.

This project is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a collaborative effort between OCCRP and Transparency International to fight corruption by combining investigative journalism and grassroots activism.