Chadwick Johnson was excited, at first, to hear that big money from Russia was on its way to save his job in South Carolina.

Months earlier, the seasoned live entertainment manager had upended his life, moving from Florida to work at the new Hard Rock Park in Myrtle Beach.

The April 2008 grand opening of the US$400 million rock-themed amusement park featured rock ‘n’ roll legends the Eagles and the Moody Blues. Thousands of guests lined up to ride the Led Zeppelin-inspired roller coaster. But after just one summer season, in the midst of that year’s economic crisis, the amusement park filed for bankruptcy and shut down.

It was a lifeline, then, when foreign investors bought the park in February 2009.

“We heard there was a Russian billionaire that bought it for $25 million, and we were going to have our jobs again,” Johnson told OCCRP. “I had a chance to hopefully keep my house and keep a job and career I’d worked so hard at.”

Instead, the purchase kicked off a scheme of fraudulent loans and shady financial transfers that put the resurrected park — now branded as the Freestyle Music Park — out of business as well, leaving dozens of American contractors and workers in the lurch after just one summer of operation. Meanwhile, the wealthy Russian investors vanished amidst a flurry of lawsuits before moving on to new projects unscathed.

Johnson was one of 17 employees who unsuccessfully sued to recover a total of over $230,000 in unpaid wages and bonuses.

“I lost everything,” said Johnson. “I got really sick, lost all my property and ended up moving back to Florida.”

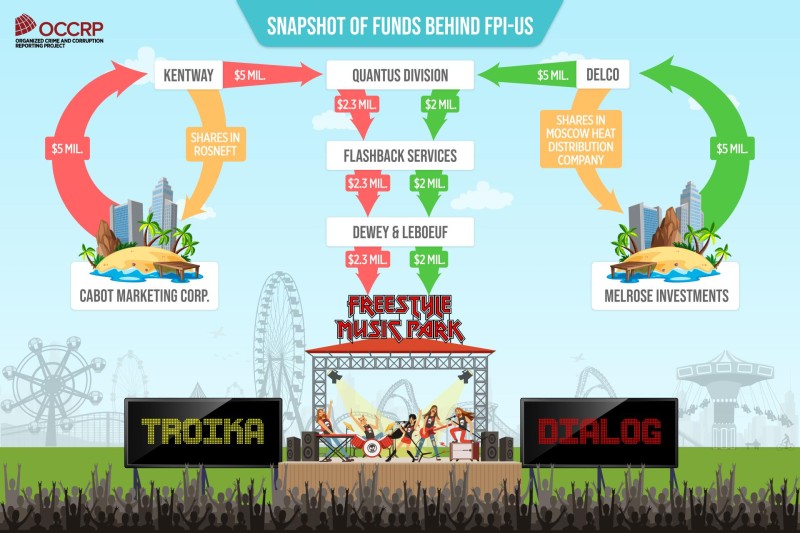

Evidence obtained by OCCRP reveals that the scheme relied on the Troika Laundromat, a system of offshore shell companies built by the Russian investment bank Troika Dialog. The network moved billions of dollars around the world, mostly out of Russia, between 2006 and 2013. Documents show that the parts of the network that were involved in the amusement park continued to transfer millions, long after its owner told U.S. courts it couldn’t afford to pay its debts.

The Delaware Fraud

Themed-attractions consultant Steven Baker was among several U.S. businessmen who sought to take over the bankrupt Hard Rock Park in 2008, but the group needed a financier. Baker turned to MT Development, a Moscow real estate firm he was already partnering with on a separate project in Russia.

He said the Moscow firm’s executives — Alexei Sidnev and Aleksandrs Timofejevs — pitched the idea to Andrey Rappoport, a billionaire who oversaw Russia’s sprawling state energy firms in the 2000s. Rappoport agreed to provide the capital.

To purchase the park, the Russian and American businessmen formed a company called FPI MB Entertainment LLC (FPI-MBE) in Delaware. Though described at the time as a joint venture between U.S. investors and a stateside “affiliate” of the Moscow firm, it was almost entirely controlled by the Russians who brokered the deal and set up its ownership structure, Baker told OCCRP.

(However, Sidnev told OCCRP that the corporate structure was drafted by the U.S. law firm Dewey & Leboeuf before it was amended by Troika Dialog and approved by Rappoport.)

After a generic makeover to strip the Hard Rock branding, Freestyle Music Park opened in May 2009. Within months it was in a legal and financial quagmire, hit by dozens of lawsuits over copyright infringement and missed payments.

“[Rappoport] provided some operating capital after we bought it, but certainly not enough,” said Baker, who had become the park’s president. “Before the Fourth of July, he told me to close it. I talked him into letting us try to run it and break even. We’d run out of cash flow. We had no more money from them.”

Rappoport communicated with Baker through “his guys,” Sidnev and Timofejevs. The billionaire attempted to disguise his involvement.

August 2009 court filings by a former FPI-MBE partner said the venture’s principal financial benefactor “insisted on remaining anonymously known as Mr. X.”

Similarly, Rappoport’s financing methods appear to have been designed to be untraceable.

To fund park operations, FPI-MBE borrowed millions of dollars from MT Development’s U.S. “affiliate,” FPI US LLC (FPI-US), using the park as collateral. Though borrower and lender claimed to be distinct entities, both were incorporated in Delaware on the same day by the same agency — and both shared the same address and phone number.

Freestyle Music Park closed for good after one summer season. FPI-US, the lender, filed a foreclosure motion in 2010 against FPI-MBE, seeking to seize the park over $24 million of unpaid debts. FPI-MBE also owed more than a dozen contractors for their labor, and the foreclosure would see those debts written off.

Several plaintiffs cried fraud, accusing FPI-US of being an alter-ego of FPI-MBE, created specifically to shield the three Russian businessmen’s money, wipe out the park’s debts, and allow them to retain ownership. During the court case, the lawyers of the FPI companies even switched sides. (FPI-US's lawyers denied that Rappoport, Sidnev and Timofejevs were its owners.)

Leaked documents and data confirm that the two Delaware companies were indeed acting in unison. For example, their tax notices were filed together, and law firm Nexsen Pruet billed both companies in the same invoice. The companies received funds at the same time from the same financial pipelines and offshore entities that comprised the Troika Laundromat.

In effect, by seeking to “seize” the park from themselves, the Russian investors managed to retain possession of the property despite having run it into the ground and failed to make payments to contractors.

By August 2010, FPI-MBE had stopped responding to court summons and its directors had resigned, save for a single member, appointed by the park’s Russian investors, Baker said.

Sidnev and Timofejevs — the Russian investors Baker described as Rappoport’s ”guys” — said they weren’t in a position to comment on what unfolded. Rappoport didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A Repeat Ride

The South Carolina park was not Rappoport’s first ride.

From Rosneft to Roller Coasters

The leaked data obtained by OCCRP sheds light on the source of some of the money Rappoport invested. The Troika Laundromat’s byzantine network of offshore companies funnelled over $60 million through companies and accounts associated with the park, and to the law firms representing them.

This includes the $25 million that FPI-MBE used to buy the venue. At least $11 million of that money came from the sale of shares in Rosneft, Russia’s state-owned oil and gas company, by a secretive offshore entity that was part of the Troika Laundromat.

According to court documents, the bankrupt Hard Rock Park’s trustees, including Deutsche Bank, were initially suspicious about the new investors’ clandestine partner from Russia and demanded more disclosure, which “proved somewhat delicate” because of the financier’s insistence on anonymity.

But the matter was resolved. “Quickly, though, a combination of wiring a $2.3 million deposit to Deutsche Bank and Deutsche Bank’s own internal checks within its Russian facilities sufficiently satisfied concerns over funding,” the document states. The money came from Flashback Services, a Laundromat company registered in the British Virgin Islands.

In fact, it was Flashback — not FPI-US — that gave FPI-MBE money to operate the park, depositing funds mainly into an escrow account managed by the U.S. law firm Dewey & Leboeuf.

Sidnev said that the offshore entities that funded the park were provided by Troika Dialog. “We knew the money was coming from the investor,” he told OCCRP.

Once again, the funds can be traced to sales of Rosneft shares, as well as another state energy business, Moscow Heat Distribution Company, which supplies heating and hot water to the Russian capital and surrounding region.

“Somebody made money”

In 2011, FPI-US won its foreclosure motion against FPI-MBE’s defaulted mortgage loan, and then bought the park for $7 million in a public auction ordered by the court. Shortly after, using the park as collateral, FPI-US borrowed $20 million from another mysterious company registered in the British Virgin Islands, Ysanne Trading Ltd.

Ysanne Trading had just been incorporated by Troika Dialog as part of the Laundromat. Leaked bank data shows that it, too, was associated with the two Delaware firms, even paying their corporate taxes.

The arrangement appears to repeat the scheme used earlier by the two Delaware companies whereby debts that used the park as collateral could be claimed at any time to prevent it from being seized by anyone else.

Though the money kept flowing through these companies, Freestyle Music Park never reopened. In January 2019, former Myrtle Beach Mayor John Rhodes purchased the land, telling a local newspaper that the Russian sellers had repaid their $20 million mortgage, and had made significantly more money by selling the park’s rides.

“Somebody made money, but I didn't,” said Vincent Lehotsky, a former attendant at Freestyle Music Park, who told OCCRP that he never received his final paycheck.

“The only ones that are going to make money are those who scammed us. Those who didn't pay us, and the lawyers,’’ he said. “These Freestyle Park owners, if they're in Russia, are not going to be brought to court.”

Where are they now?

Freestyle Music Park wasn’t Sidnev and Timofejev’s only financial scandal that began in 2009.

Additional reporting by Katarina Sabados

Correction, July 31, 2019: The story has been updated to remove an erroneous reference to Andrey Rappoport's relationship with the Moscow Heat Distribution Company. OCCRP regrets the error.