In December 2021, a welcome delivery arrived in Moscow just in time for the holidays: A refrigerated train full of fresh grapes, persimmons, lemons, and tomatoes straight from the sunnier Uzbek capital of Tashkent.

It was the pilot run of the new “Agroexpress,” a railroad delivery service conceived as part of a new trade agreement between Uzbekistan and Russia.

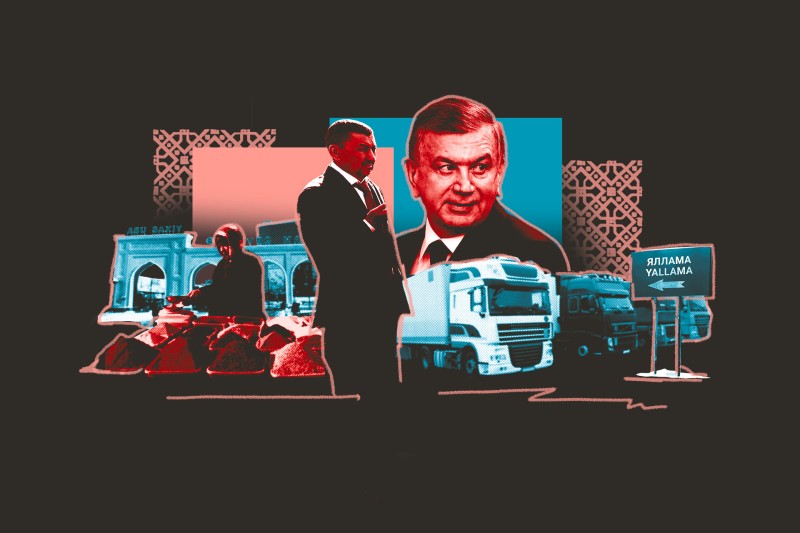

Though Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and subsequent Western sanctions, were still months away, Russian President Vladimir Putin was already on the hunt for closer trading ties with his nearer neighbors — and Uzbekistan’s president Shavkat Mirziyoyev seemed happy to oblige.

But, as one of the logos on the side of the train revealed, the Agroexpress project had an obscure private partner: a company that had just been founded the previous year.

This firm, called UTI Transit, was not just a newcomer. It is owned by the Abdukadyrs, a notorious family of Chinese-born Uighurs that had allegedly built a vast underground smuggling empire through bribery and corruption.

In a series of investigations, OCCRP, RFE/RL and Kloop had revealed that, led by Khabibula Abdukadyr, the eldest of four brothers, the family systematically consolidated control over key trade routes in neighboring Kyrgyzstan by paying off a top official and securing privileged treatment at customs facilities.

These findings were widely covered in the region. But after over a year of investigating the Abdukadyrs’ latest business dealings, reporters have found that the family has followed a similar playbook in Uzbekistan: gaining control over a major bazaar, dominating trade routes, and partnering with the customs service. This time, however, they secured their position not through under-the-table deals, but with government support.

First, the Uzbek authorities launched an anti-corruption campaign against the owner of the most important market in Tashkent, subjecting it to so many inspections that he finally sold it to the Abdukadyrs. According to multiple sources, the Abdukadyr family is backed in this business by President Mirziyoyev’s son-in-law, Оtabek Umarov.

The family has also partnered with the government directly, establishing a joint trucking venture with a state firm that helped implement a highly-touted new trade route from China.

In another case, even before the Uzbek government publicly announced its plans to build several new customs terminals on the country’s borders, documents show the Abdukadyrs were already working with officials to get the project going. The family has invested in two of the terminals and now operates them; more are planned.

Even their company’s partnership in the Agroexpress train project was reportedly secured through the recommendation of a state firm.

Kristian Lasslett, a professor of criminology at Ulster University who has studied the Abdukadyr family, says that the country presents a ripe target.

“The benefit is that you go into Uzbekistan, where the economy is growing, and there are opportunities to make profitable, large-scale investments without any [government] checks. … It’s real fertile territory. They were obviously reintegrating themselves into the new power center.”

Bruce Pannier, a journalist affiliated with RFE/RL and long-time Central Asia specialist, agrees that the Abdukadyr family’s success is a testament to their power and influence.

“The fact that [Khabibula Abdukadyr] was able to get this prize market … shows the kind of clout that he carried in Uzbekistan. He’s either so well connected or so invaluable to somebody, that this was a deal that was acceptable to powerful people.”

In particular, Pannier described the family’s access to customs terminals as “disturbing.”

“The fact that these people are present in Uzbekistan at customs posts, you have to wonder — who’s actually in charge here? Is it the customs service? Or is [Khabibula Abdukadyr] basically running the show, and the customs service are just kind of his employees at this point?”

“It does show a degree of connection that you hate to see any controversial figure have with any government.”

Reporters sent over 50 requests for comment to the people, organizations, and government institutions named in this investigative series. Most did not respond, including President Mirziyoyev’s administration, the Uzbek customs service, the Uzbek and Russian state railways, and Otabek Umarov. The Abdukadyr family acknowledged receiving questions from an email address known to be used by Khabibula Abdukadyr, but said they could provide information only at a later date.

The Epicenter of Uzbek Trade

In Uzbekistan’s trading sector, there is no bigger prize than the Abu Sahiy market. Its endless traders’ rows{:target=_blank"} sprawl along the capital’s ring road, selling every imaginable good, from clothes to home electronics. The market is so full of Chinese imports that local comedians call it the “capital of China.” For the convenience of its shoppers, it has food stalls, multi-story parking garages, and even its own mosque.

The origins of Abu Sahiy are murky, but for years, it was owned by Timur Tillayev, the jet-setting son-in-law of Uzbekistan’s long-time president, Islam Karimov.

Tillayev allegedly extracted millions from import flows to the market, his profits reportedly fuelled by unofficial tax and customs preferences that enabled him to undersell the competition.

He has always denied these allegations, and his lawyer continues to deny them today. But, as revealed in a series of investigations published by OCCRP and partners several years ago, one of the market’s main suppliers during those years was Khabibula Abdukadyr.

With the help of corrupt customs officials in neighboring Kyrgyzstan, Abdukadyr and his brothers made a fortune allegedly selling falsely labeled and under-declared Chinese goods at Abu Sahiy. The family employed a self-confessed money launderer — later shot dead in Istanbul — who said he used a variety of illicit schemes to send their profits to bank accounts across the world.

The arrangement persisted for years. Both Tillayev and Abdukadyr got rich, and Abu Sahiy kept growing. But in a country like Uzbekistan, where so much depends on the graces of those at the top, things can change quickly. And for a savvy man like Abdukadyr, change can represent an even greater opportunity.

In 2016, President Karimov died and his prime minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, took power. Uzbekistan’s new leader portrayed himself as a reformer who would open the country to the world, end human rights abuses, and clean up corruption. It was little surprise that Tillayev, a prominent member of the former ruling family, appeared in his crosshairs.

Prosecutors and tax and customs officials launched a series of inspections against the previously untouchable Abu Sahiy market. Business took a hit, with cargo operations halting for weeks. Finally, at the end of 2017, Tillyaev was out, selling his stake in the market to new owners. He is not known to have set foot in the country since then.

The government portrayed Abu Sahiy’s change of ownership as a major shakeup. Within a few weeks, the office of Mirziyoyev himself was already promoting the market’s newfound respectability, praising its skyrocketing tax payments.

Several months later, a glowing report on state television extolled the unnamed “foreign investors with international experience” who now owned Abu Sahiy. The program aired interviews with happy shoppers who said prices had decreased and traders who praised lower rent payments.

As it turns out, the “foreign investors” who took over Abu Sahiy are the Abdukadyrs. Tillayev’s lawyer confirmed in an email to reporters that his client sold the market to Khabibula Abdukadyr in December 2017. Corporate documents show that, after Tillayev’s departure, Abu Sahiy was first held by the Abdukadyr family’s German companies and then transferred to an apparent proxy: A Turkish company owned by a woman in her mid-20s who has no other known businesses.

Splitting the Spoils

In multiple interviews, sources close to the Abu Sahiy market — including traders, a corporate lawyer, a former senior police official, and cargo company owners — pointed to a powerful player they said was backing Abdukadyr from the shadows: Otabek Umarov, President Mirziyoyev’s son-in-law and the deputy head of the presidential security service.

The arrangement they describe is typical of many former Soviet countries: A member of the ruling political elite, in this case Umarov, steps in as the krysha, or “roof,” of a lucrative business. Often, in exchange for a cut of the profits, a krysha offers political protection, insider access, and shortcuts around regulations.

One source on the inside — a man who works for an Abdukadyr company — was able to offer the most detail, though it could not be independently corroborated.

“The shares of Abu Sahiy belong to Hoji aka [a respectful term for Abdukadyr], but he is in partnership with O[tabek] U[marov],” he said.

The worker described seeing a cash counting machine and piles of U.S. banknotes in the office of Abu Sahiy’s director, which he alleged were later delivered to Umarov as his share of the profits.

As a key link between Abdukadyr and Umarov, he pointed to another member of the presidential family: Mirziyoyev’s sister’s son-in-law, Najim Abdujabarrov. “He is a representative of the family,” the worker said, explaining that Abdujabarrov spends most of the week in the offices of Baraka Holding, one of the Abdukadyrs’ key trading companies. “He is in-between Hoji [Abdukadyr] and the sons-in-law.”

In another case, the Abdukadyr family partnered with a member of the presidential family directly. A logistics center they co-owned with a son of President Mirziyoyev’s cousin was instructed by the customs service to process all international courier shipments, driving massive business to the facility (see box for details).

CPT Pochta

How a modern new logistics center by Tashkent’s International Airport, co-owned for several years by the Abdukadyr family and Abror Mirziyayev, took over international courier shipments.

‘Instructions from the Government’

The Uzbek government has also included the Abdukadyr family in a new plan to develop a more efficient trade route between Uzbekistan and China.

In 2017, Uzbekistan’s President Mirziyoyev signed agreements with both China and Kyrgyzstan to develop a modern new trade route that would benefit all three countries.

When the Kyrgyz president traveled to Tashkent on an official visit that December, Khabibula Abdukadyr came as a member of the Kyrgyz delegation. The very next month, the family entered into official partnership with the Uzbek government: One of their Chinese companies joined a majority state-owned firm, O’rta Osiyo Trans, to establish a joint venture with the goal of “carrying out instructions from the government” — a reference to developing the new trade route.

The state was apparently determined to have the Abdukadyrs as partners, outvoting a Turkish minority shareholder of O’rta Osiyo Trans who opposed the arrangement.

The new joint venture, Silk Road International, received an infusion of cash from the Abdukadyr side and a fleet of truck trailers from the state side. In September 2018, the Uzbek trade ministry proudly announced that the company had successfully established the new route, its trucks plying the roads between China and Uzbekistan carrying food, crops, construction materials, and consumer goods.

In 2020, Khabibula Abdukadyr acquired the Turkish shareholder’s minority stake in O’rta Osiyo Trans, becoming a direct partner of the Uzbek state.

Between this acquisition, the Abdukadyrs’ stake in Silk Road International, and their ownership of a leading Kyrgyz trucking company called Tarim Trans, the Abdukadyrs appear to have established a dominant position supplying Chinese goods to Uzbekistan.

When reporters called representatives of over two dozen competing transportation companies, a majority said they could not deliver cargo from China to Uzbekistan by road. Those that have attempted to do so complained of excessive wait times and uncertainty as to whether the cargo would arrive at all. “We are afraid to use this route,” one said, suggesting that his company was asked to pay a bribe to get its cargo through. Most of the Abdukadyrs’ competitors were using an alternative route not dominated by the family: sending the goods by rail through neighboring Kazakhstan.

In addition to physically carrying goods, the Abdukadyrs’ Uzbek trading company, Baraka Holding, is used by traders around the country as an intermediary when ordering and importing goods from abroad.

The company handles all the import procedures and customs paperwork itself, enabling its customers to purchase their imported goods from a “domestic” supplier.

This is an arrangement that Baraka’s competitors apparently can’t match. RFE/RL’s Uzbek service has received a number of anonymous messages from traders and cargo company owners complaining that using Baraka Holding was essentially their only option.

“Any merchant who imports anything from abroad must ship goods only via Abu Sahiy/Baraka logistics,” one trader wrote. “Otherwise they will not be able to have them cleared at the customs office.”

According to Uzbek government data, in 2022 Baraka Holding was the country’s third-largest trading company by turnover, with income of over $200 million. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

‘I Don’t Think There Were Any Competitors’

Although they were once accused of bribing a senior customs official in neighboring Kyrgyzstan, the Abdukadyr family is now in a formal partnership with Uzbekistan’s customs agency.

In January 2019, Mirziyoyev’s government invited private companies to submit bids to build four new customs terminals on the country’s borders.

The announcement, which gave a deadline of only 10 days, noted that the government’s potential partners needed to fulfill a number of conditions even to pass the pre-qualification phase.

Among these was having experience building at least two terminals, including abroad; five years’ experience in managing such terminals; a positive international image; and share capital of at least $9.5 million.

The winner of the tender was never announced. But land ownership data and a government list of foreign direct investment in Uzbekistan reveal who is implementing the project: a company that fulfilled none of these conditions. It does not even have a web site, and in fact had been incorporated just three months before the tender was announced.

“I think it was decided on some upper or higher level,” a source who worked on the project said. “I don’t think there was any competition.”

This firm, the Euroasia Transportation and Logistics Company (ETLC), is held by the German-incorporated Hyper Partners. This company is owned by a 23-year-old with the last name “Palvan” — which is also used by Khabibula Abdukadyr and his brothers — and whose address in corporate filings is the family’s London mansion. This suggests he is a member of the family.

The four terminals are in various stages of completion; at the time of publication two were already operational.

The construction of another five terminals, representing the second phase of the project, was put out to tender in early 2020. Though no winner has been announced, ETLC owns a plot of land near at least one of them.

As a matter of fact, it appears that no other company ever had a chance. A set of internal documents from Hyper Finance Group, a company that appears to manage some of the family’s major real estate projects, was obtained by reporters. They show that, by the time the president’s plans to build the terminals became public, Abdukadyr companies had already completed extensive design work in collaboration with government officials.

One PowerPoint presentation sets out plans for the construction of five terminals and logistics centers to be “initiated” jointly by an Abdukadyr company called AKA Group, the customs service, and the state railway company. The metadata shows that the file was last modified in August 2018, months before the customs terminals project was announced.

By the time President Mirziyoyev released a decree ordering the “improvement of customs administration” in Uzbekistan, Hyper Finance was already well on the way to completing the work. A folder obtained by reporters and dated November 16, 2018, contains designs for the same nine new terminals the president would announce eight days later.

Hyper Finance even seemed to know in advance which terminals to prioritize. A document dated December 10, 2018 contains a list of nine terminals and highlights four of them as the top priority. The government’s formal tender announcement, listing the same four terminals as the first phase of the project, did not come until the following month.

According to the documents, a man named Bekhzod Achilov was a key contact for Hyper Finance Group’s designers, responsible for a planned visit to an already-existing Tashkent terminal to better understand customs procedures. Just months earlier, Achilov was serving on the board of a state agency that issues certifications for imported goods and other products. He also worked at the foreign trade ministry.

Later, Uzbek corporate records revealed a more direct link between Achilov and the Abdukadyrs’ customs terminals business: He was the listed director of ETLC, the firm behind them. Achilov’s personal e-mail was a listed contact for the firm.

With control over multiple customs terminals and the vast Abu Sahiy market, a family that made its fortune in alleged smuggling had — with the collaboration of government agencies — secured a grip over much of the land-based trade flowing in and out of Uzbekistan.

Russia is Next

Now, their plans are stretching even wider.

As Russian trade reorients from the West toward Central Asia and China, Uzbekistan has the potential to become a crucial intermediary — and the family is poised to try to take advantage.

According to the country’s minister of transport, the government plans to expand Agroexpress, the train project in which Abdukadyrs are a key player, to carry goods to and from other Russian destinations in the Urals and the Far East.

Meanwhile, a new joint venture between the Abdukadyrs’ UTI Transit and the Russian Railways is seeking to attract customers on new routes between Moscow and China, as well as China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.