In August 2020, Paul Rusesabagina, a Rwandan dissident and the inspiration for the award-winning movie Hotel Rwanda, left his home in Texas to fly to Burundi for a speaking tour. When he landed in Dubai to change planes, he sent a WhatsApp message to his family to say happy birthday to his grandson.

Then he disappeared.

Four days later, Rusesabagina emerged on television in Rwanda, handcuffed and escorted by officers. In a bold and complex operation, Rwandan authorities had tricked Rusesabagina onto a private plane in Dubai. It flew him not to Burundi, as he believed, but to Rwanda, where he faced charges of financing terrorist activities.

His adopted daughter, Carine Kanimba, a U.S. and Belgian citizen, soon launched a campaign to free her father. She never set foot in Rwanda — but it is likely the government in Kigali had her under close watch, thanks to cutting-edge and highly invasive Israeli spyware that was placed on her phone.

For almost six months, until as recently as July 3, Kanimba’s cell phone was bombarded with Pegasus, malicious software manufactured by Israeli tech firm NSO Group, according to research by OCCRP and The Pegasus Project, a global consortium of journalists coordinated by Forbidden Stories. Forensic analysis by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, which lent technical assistance to the project, found that Kanimba’s phone was successfully infected with Pegasus multiple times.

When Pegasus is implanted on a device, it effectively gives an attacker complete access to the target’s phone. It can read messages and passwords, access social media, use GPS to locate the target, listen to the target’s conversations, and even record them. End-to-end encryption, available through popular apps like Signal, does not protect against Pegasus once the phone is compromised.

In a series of responses, NSO Group said Pegasus is sold only to governments to go after criminals and terrorists, and has saved many lives. It denied that its spyware was systematically misused and challenged the validity of data obtained by reporters.

As part of the investigation, reporters obtained a list of over 50,000 numbers throughout the world believed to have been selected by NSO Group clients for targeting with Pegasus. Reporters were able to identify dozens of numbers belonging to Rwandans or other people of likely interest to Rwanda’s government from neighboring countries. They included activists, journalists, dissidents, and government officials.

Reporters were unable to conduct forensic analyses to verify infection on these phones, but the extent and nature of the Rwandan numbers in the data strongly suggests that the Rwandan government was a client of NSO Group. There’s also a history of Pegasus being used against Rwandan dissidents. In 2019, a number of Rwandans were among 1,400 victims of Pegasus attack using a vulnerability in the messaging application WhatsApp that became the basis of a lawsuit by Facebook against NSO Group.

Three Western government officials told OCCRP, on the basis of anonymity, that they were aware that Rwanda had access to advanced Israeli spyware technology, and that there was concern at how it was being deployed.

Dr. Vincent Biruta, Rwanda’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, said Rwanda does not use or have access to Pegasus. He dismissed the hacking of Kanimba’s phone and the potential targeting of activists, journalists, lawyers, politicians, and others as “false accusations.”

Kanimba’s number was not on the list of potential targets, but The Pegasus Project decided to approach her separately as a likely victim. A subsequent forensic analysis verified that her phone was infected. Many others on the list were not approached to conduct forensics before publication out of concern that a leak could undermine the security of the journalistic collaboration, or put targets in danger.

Rusesabagina has been a high-profile critic of Rwanda’s government for many years. He was the manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali during the genocide and helped shelter and save nearly 1,300 people, acts that inspired the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda. Rusesabagina fled Rwanda in 1996, ending up in the U.S. where he was eventually granted the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush.

In exile, Rusesabagina helped set up a coalition of opposition groups. Rwanda has accused him of a raft of terrorism-related offenses. His daughter, Kanimba, told Pegasus Project reporters that the charges are groundless and that Kagame is jealous of Rusesabagina.

“A running joke in our family is that Kagame thinks about us every night before going to bed,” she said during an interview with Pegasus Project member Knack, a Belgian magazine.

“I wasn’t shocked [about being targeted]. … Because we are dealing with a dictatorship,” she said. “They are distracting me by making me think about this.”

“It’s also an intimidation tool.”

Listening In

By January 2021, while her phone was being targeted, Kanimba was in Belgium, where Rusesabagina holds citizenship, trying to organize support among European officials for her campaign. Kanimba said she was speaking to officials from several other major diplomatic powers as well.

“All of January and until February 11, I was contacting every single MEP across Europe, also the members of the EU delegation in Rwanda,” she said. She was also using her cell phone in communications with British members of parliament, as well as British and U.S. diplomats and officials. With Pegasus on Kanimba’s phone, it’s feasible that Rwandan agents could have observed and recorded all of these interactions.

Her phone continued to be attacked by Pegasus spyware throughout the first half of this year. It’s not clear why repeated attacks were needed, but researchers believe the software is not persistent and disappears or deletes itself during certain phone operations, such as rebooting.

Amnesty International’s analysis found an attack on June 14, the day Kanimba met with Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sophie Wilmès. “I had the phone in the room too,” Kanimba told reporters.

Kanimba said Rwandan officials began to act in ways that suggested they were aware of her movements, schedule, and even private conversations. Some Belgian members of parliament who had only expressed support to her privately were subsequently contacted by Rwandan officials, she said.

Kanimba told reporters of a conversation between her family and their lawyers about getting Rusesabagina to sign an affidavit describing how he was tortured while held captive.

“We hadn’t shared [this idea] with the Rwandan lawyers, but the next time our Rwandan lawyer went to see my father in prison he was searched, he was asked for a form that my father was supposed to sign,” Kanimba said. “[The Rwandan lawyer] didn’t know anything about it. We hadn’t even sent it to him. But somehow they knew to look for it.”

“Genocide Ideology”

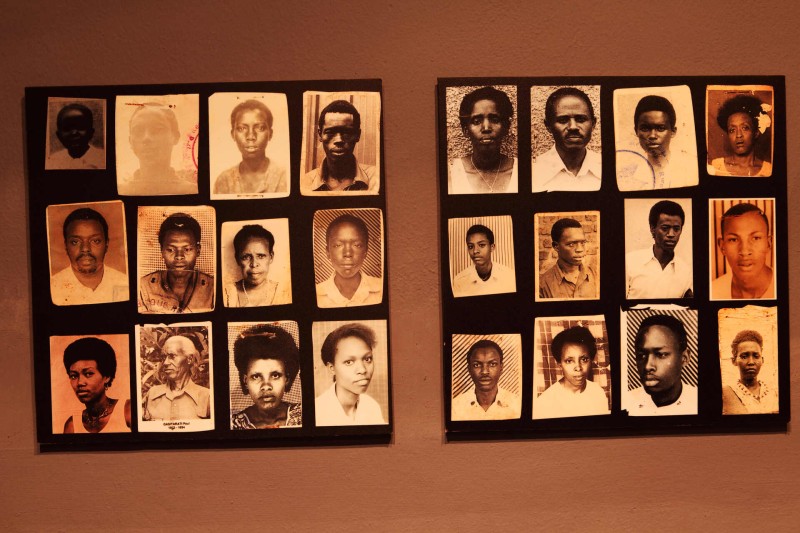

Rwanda was once the poster child for the success of Western development aid. Emerging from the ravages of the 1994 genocide, in which roughly 800,000 were killed, Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took power and brought a fragile peace and order to the tiny East African nation.

Rwanda’s Genocide

Kagame, an RPF military leader who rose in the ranks to become president in 2000, has ruled Rwanda ruthlessly but effectively. Rwandans enjoy paved roads, fewer blackouts, and a relatively thriving economy compared to other countries in the region. Tony Blair and Bill Clinton led a long procession of world leaders eager to celebrate Kagame’s “visionary leadership” in the 2000s. But criticism of his methods is growing.

Kagame raises the specter of the genocide to justify chasing and crushing his opponents at home and abroad. The RPF dismisses critics as ethnic extremists, while laws against “genocide ideology” and “sectarianism” are loosely defined, allowing the government to criminalize particularly irksome opponents.

In 2014 the government arrested the popular singer Kizito Mihigo after he released a song remembering Hutu as well as Tutsi victims of the 1994 genocide. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison for conspiring against the government. Though freed in 2018, he was captured and rearrested at the Burundian border in February 2020, and found dead in his cell days later. Rwanda claims Mihigo killed himself, but Human Rights Watch and other groups have called for an independent inquiry into his death, which they describe as suspicious.

Journalist and author Michela Wrong, the author of a recent book on Rwanda’s treatment of dissidents, described Rwanda as “a state run along intelligence lines.” Kagame was trained in military intelligence and has carried that through into his presidency, and it’s likely he is personally involved in all major decisions on espionage, she said.

“There’s no sign of any real power base outside Kagame,” Wrong told OCCRP. “When you have a top-down system of that kind, with such strong executive control, you can take it as read that all of these key decisions – taking out opponents, harassing and intimidating members of the opposition, surveillance, and monitoring – all that goes straight to Kagame.”

Assassinations Abroad

Targeting Opponents

In May this year, Cassien Ntamuhanga, a Rwandan asylum seeker and critic of Kagame’s government who had been tried alongside the singer Mihigo in 2015, was arrested by Mozambican authorities. Mozambique police denied knowledge of his detention. Human Rights Watch said that he “risks being handed over to Rwanda.”

Now, reporting by The Pegasus Project has found that Ntamuhanga’s Dutch phone number was on the list of numbers selected by NSO Group clients for targeting with Pegasus.

It’s not known if any of the Rwandans whose numbers appear on the list were successfully hacked. However, forensic checks of phones around the world from the list showed that, of those that could be tested, 84 percent showed signs of successful or attempted infection.

Another Kagame critic on the list is David Himbara, who lives in Canada and runs a prominent blog. His number was selected for targeting in early 2019, though forensic analysis of his cell phone did not find traces of an attack. Himbara told the Guardian, a participant in The Pegasus Project, that he believes Kagame poses a threat to his life.

As well as critics, the Kagame government may have targeted lawyers working against its interests. A South African phone number for lawyer and RNC spokesman Frank Ntwali was added to the list between 2017 and 2019. Ntwali was the target of a failed assassination attempt in 2012, and was one of the Rwandans allegedly hacked by Pegasus via WhatsApp in 2019.

Both Karegeya’s former lawyer and Rusesabagina’s Rwandan lawyer were selected as targets between 2017 and 2018. Several journalists in Rwanda, Uganda, and DRC were also on the list.

Other than in the case of David Himbara, reporters were unable to carry out forensic analyses on their phones due to security concerns.

Diplomatic Espionage

The list of selected numbers also shows the Kagame government may have used Pegasus to target high-ranking political and military figures in neighboring countries.

Several numbers for high-profile figures in Uganda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) feature in the data. Rwanda has had frosty relations with these neighbors over the years. It has sponsored armed groups in the east of DRC, criticized Uganda for harboring anti-RPF militias, and been accused by Burundi of plotting to overthrow its president.

Telephone numbers for Ruhakana Rugunda, the prime minister of Uganda until last month, and Alain-Guillaume Bunyoni, the prime minister of Burundi, appear on the list. Bunyoni was added before he was appointed prime minister, when he was Burundi’s interior minister.

Among the Ugandans on the list, OCCRP has identified numbers belonging to longtime senior cabinet member Sam Kutesa, former Defense Forces Chief General David Muhoozi, senior intelligence officer Joseph Ocwet, and leading opposition figure Fred Nyanzi Ssentamu. The selections coincided with a visit by Kagame to Uganda.

In DRC, OCCRP identified numbers in the data for Lambert Mende and Albert Yuma, both powerful allies of longtime former President Joseph Kabila, who stepped down in January 2019. Reporters also found a number belonging to Jean Bamanisa Saïdi, a prominent provincial governor in DRC’s gold-rich east. These numbers were selected around the time of a political crisis in DRC over whether Kabila would respect constitutional term limits.

“There is already enormous, well-founded suspicion between the governments in the Great Lakes region and Rwanda,” said journalist Michela Wrong. “[Evidence of spying] will certainly encourage the view that Rwanda is not a partner playing by the rules.”

Spokespeople for the DRC and Burundi declined to comment. A Ugandan government spokesperson, Ofwono Opondo, said that it is “up to Uganda to strengthen its cyber security protocols, otherwise the world is full of spying and espionage even among allies.”

“In the Claws of the Monster”

Back in Brussels, Kanimba says she has purchased a new phone and continued her campaign to free her father. The campaign has enjoyed some recent successes. On June 23, members of the U.S. Congress from both parties sent a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressing concern over the detention of Rusesabagina. The next day, the Belgian parliament called for Rusesabagina to be freed and allowed to return to Belgium.

Earlier, in February, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning the “enforced disappearance, illegal rendition and incommunicado detention” of Rusesabagina.

Meanwhile Rusesabagina’s trial in Kigali has resumed after a hiatus. In March, he refused to participate any further in the trial, writing in a letter to the court that he did not expect justice to be served.

“We know that emotionally he is a very strong man,” said Kanimba. But she and her family are anxious about the 67-year-old’s health. “He has hypertension. He has a heart condition. He is a cancer survivor … This is what scares us the most.”

“My father is in the claws of the monster. So we have to get him out.”