Konstantin Ernst once dreamed of making movies. As the Soviet Union entered its final years, the son of a well-known cattle breeding specialist left his own scientific career behind to spend time with filmmakers and shoot music videos.

He later excelled in television more than in cinema, quickly becoming a groundbreaking producer. In the late 1980s, the show Viewpoint, where he started his career, was a staple for Soviet citizens who had grown tired of stale government programming. His arts-and-culture, Matador, was "unlike anything previously seen on Russian television," the New Yorker wrote in a recent profile.

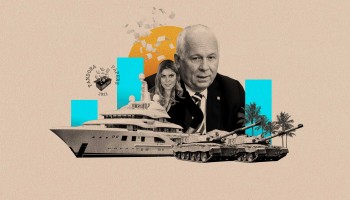

But in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Ernst has put his skills to much different use, becoming an influential purveyor of state propaganda as head of Channel One, one of the country’s main pro-government outlets.

In 2004, when hundreds of children were killed during a botched operation by Russian forces to rescue them from Chechen terrorists, the channel reportedly downplayed the number of hostages involved, and even aired a Brazilian telenovela. It has also broadcast anti-Ukrainian storylines, including reports implying that it was actually a Ukrainian fighter jet — not pro-Russian separatists — that shot down a Malaysian airliner in 2014.

Such questionable content is financed in part by Russian taxpayers. Over the past five years, Channel One has been allocated state subsidies totaling more than 10 billion rubles ($138 million), while the channel's losses over the same period amounted to more than nine billion rubles ($124 million).

Despite these lamentable financials, Ernst has been lauded for his work as the channel’s director, a position he has held for two decades. Earlier this year, Putin awarded him the Order of Merit for the Fatherland.

But the Channel One boss may have been rewarded in another, less public way.

Reporters from IStories, OCCRP’s Russian partner, have learned that Ernst’s offshore company received a loan from a state-connected bank that enabled him to acquire a considerable stake in a $1 billion project to reconstruct dozens of Moscow movie theaters, including several classic examples of Soviet modernist architecture.

Another company partially owned by Ernst received at least 25.6 billion rubles ($353 million) from a state bank to invest in the project.

Ernst’s involvement in the scheme has been carefully concealed by his lawyers and partners — perhaps because this “reconstruction” ended not with the restoration but the demolition of the theaters, including the historical landmarks.

Offshores and Cinemas

On February 7, 2014, the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics took place at the Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi. The ceremony organizers, led by Konstantin Ernst, meticulously planned the occasion to showcase Russia's place in world culture and history.

That very day, in the distant British Virgin Islands, a local corporate services agency registered a company called Moscow Dvorik Ltd. Eight months later, Ernst became the sole shareholder of another BVI company, Haldis Corporation, which soon acquired a stake in Moscow Dvorik.

Though the BVI has a population of just over 30,000, about one million offshore firms are registered there. The reasons include tax advantages, British corporate law, and secrecy: the local corporate registry does not disclose data on company owners.

But Ernst’s involvement with such offshore companies, and their relation to the Moscow movie theater project, has now been uncovered in the Pandora Papers, a set of millions of corporate documents leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with partners around the world, including OCCRP and IStories.

In November 2014, a month after Ernst took possession of his offshore company, Haldis Corporation, Moscow City Hall held a huge state auction at which city authorities offered 39 local movie theaters for sale. These included the Sofia, the Baku and the Vityaz — iconic Soviet-era facilities.

Though some of the theaters had fallen into disrepair and held little architectural value, many were held dear by Muscovites not only for their sought-after film screenings, but also for their aesthetics.

“In my opinion, one of the most unique constructions of the 1970s was an idiosyncratic, non-typical work — the ‘Baku’ theater,” says Denis Romodin, an architectural historian and senior research associate of the Moscow Museum. “It was finished with Azerbaijani sandstone, you can see all the elements of eastern architecture. All these cinemas had their own vivid, expressive look.”

In the end, all 39 were snapped up — for the minimum price allowed under the terms of the auction — by a company called Edisonenergo, part of ADG Group, which was founded by brothers Mikhail and Grigory Pechersky in 2004.

At the time, residents who feared the theaters would be knocked down and turned into shopping malls were outraged. Dmitry Baranovsky, a municipal lawmaker in Moscow, tried in vain to save the Soviet modernist Sofia theater in his neighborhood of North Izmailovo.

“The ‘Sofia’ was a symbol of Northern Izmailovo,” Baranovsky told reporters earlier this year. “This is kind of a historical and cultural heritage of the district. They demolished the cinema, and the district lost this face.”

At auction, the Sofia was valued at 930 million rubles ($16.4 million), although a year earlier, when authorities had unsuccessfully tried to sell five of the 39 cinemas, it had been valued at 1.5 billion rubles ($45.8 million).

After the sale, Baranovsky made a complaint to the Federal Antimonopoly Service, saying the cinemas had been sold for below their true value and that the law prohibits the privatization of active cultural facilities.

In total, the cadastral value of all 39 theaters was about 23 billion rubles ($406 million), a sum which itself understated their true market value. But the mayor's office set an initial firesale price of just 9.6 billion rubles ($169 million) — and all 39 were handed over to Edisonenergo for this sum, without any competitive bidding.

Moscow’s anti-monopoly authority, which considered the case Baranovsky raised, agreed that when it came to the decided price of the theaters, and their privatization, laws may have been broken. However, a commission decided there had not been “a violation of the anti-monopoly legislation,” and the complaint was rejected.

"It was clear that this lot was organized for a specific large buyer. This buyer turned out to be ADG Group," Baranovsky told reporters. And behind ADG, reporting shows, was Channel One’s Ernst, whose offshore firm let him act as a secret partner in the deal.

‘A Beautiful Story’

Grigory Pechersky of ADG Group estimated in an interview with business daily Vedomosti that the total investment made by ADG’s Edisonenergo into the reconstruction of the cinemas was about 60 billion rubles ($831 million). VTB, a Russian state bank, provided a credit line of 46 billion rubles ($637 million), of which at least 25.6 billion rubles ($353 million) were actually loaned.

Given the large amount of financing involved and the circumstances of the sale, many suspected someone influential was behind the project. In 2017, journalists from Kommersant put the question to Pechersky directly. Rumours were swirling that Ernst was involved, they said. Was that true?

“That would be a very beautiful story,” Pechersky replied. “But, alas, it's not the case.”

Documents from the Pandora Papers show otherwise.

As it turns out, through another company called Dvorik Cyprus, Edisonenergo is partially owned by the same Moscow Dvorik that was registered on the opening day of the Sochi Olympics.

And in December 2014, Ernst’s BVI company, Haldis Corporation, became the largest shareholder of Moscow Dvorik, purchasing almost half of its shares. This gave Ernst a 23 percent stake in the nearly $1 billion movie theater restoration project.

The money for this acquisition — an $16.2 million loan — came from RCB Bank, a Cyprus-based lender partially owned by the Russian state bank VTB. Ernst used his own shares in Haldis as collateral for the loan.

In effect, putting in none of his own money, he had acquired a substantial portion of a highly publicized project supposedly funded entirely by ADG Group’s wealthy owner.

Ernst's involvement was carefully concealed, and not only by ADG Group head Pechersky. After Haldis was granted the loan, the service provider that registered it was supposed to inform the BVI’s commercial register. But the lawyers who serviced Ernst's firm apparently feared that this information could become publicly available.

“Please do not arrange for the annotated share register [shareholder information] to be filed at the Registry of Corporate Affairs,” one of them wrote to his colleagues in early 2015. “The non-filing of the share register … and the original share register to be maintained at the Company’s registered office in the British Virgin Islands, are conditions of the financing provided by RCB Bank.”

In a response to reporters’ inquiries, RCB’s head of corporate affairs, Maratheftis Michalis, wrote in an email: “We want to categorically state that we meticulously follow all the regulations and requirements of each [lending] case.”

“That is, we file whenever that is required and do not do so when and if that is not required.”

Everything Was Demolished

In the end, it seems, Konstantin Ernst realized his childhood dream of getting into cinema, although he will leave a legacy that includes cinematic destruction.

Initially, the owners of ADG Group said that the theaters they had bought were going to be reconstructed. “The mission of the project is to restore the historical function of the Soviet movie theaters as centers of life in Moscow's bedroom communities," Grigory Pechersky said.

He was echoed by the mayor's office, which said that the sale and redevelopment of the cinemas would herald “a fundamentally new concept for Moscow of district ‘attraction centers.’”

But in the end, the vast majority of the 39 cinemas were demolished to make way for new buildings that look very much like typical shopping centers.

"Well, obviously it’s a shopping center,” said Dmitry Baranovsky, when asked about the building built on the site of the old Sofia theater, which is not yet open to the public.

“It was clear from the beginning that it would be a shopping center, because the documents defined the percentage of space that could be allocated for a cultural institution and for shopping. Most of the cinemas had varying proportions. Some, like the Sofia, have up to 100 percent retail space. Other cinemas have 30 percent [reserved for] cultural space.”

The new building “has completely destroyed this wonderful, unique modernist ensemble which we had here in Northern Izmailovo,” lamented Moscow historian Anastasia Solovyova.

Romodin, the architectural historian, said that most of the buildings once had "a bright, individual facade," but the shopping malls inserted in their place were standardized projects with little variation.

Representatives of ADG Group declined to speak with IStories.

In his response to inquiries from ICIJ, Konstantin Ernst said that he hadn’t “committed any illegal actions. Nor am I committing any now, or about to. This is how my parents raised me.”

Ernst admitted his involvement in the Moskovsky Dvorik project. “I’ve never made a secret of that,” he said, despite his partner Pechersky’s denials and the elaborate offshore structures that concealed his role.

“But that is not the compensation for the Olympics 2014. The compensation for my involvement in the Olympic Opening Ceremony was 1 ruble.”

“In all seriousness, I’m not going to answer your questions,” he continued. “Not because I’m afraid of anything, only because I’m more than sure you are not an independent investigation company but an organisation commissioned by the US secret services. And that has nothing to do with independent journalism.”

.jpg/daf5f209c20846c8dcd2295cae2a00ae/kenyan-aladdin-sep24-(1).jpg)