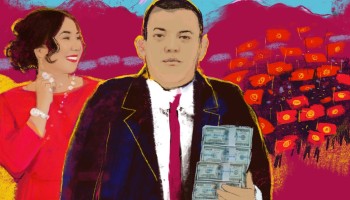

At long last, Raimbek Matraimov was going to be giving instead of taking.

The former Kyrgyz customs official, nicknamed Raim-Million for his immense wealth, agreed in October to repay 2 billion soms (US$24 million) to compensate his government for years of corruption.

His admission of guilt and repayment of a substantial sum was seen by some as a step forward in a country where corruption had long run rampant.

However, his much-publicized compensation was not what it seemed, OCCRP and Kloop have discovered. Nearly a third of it was made in the form of 10 properties he handed over to the state. He had acquired them just days before offering them as repayment, for reasons that remain unclear.

The most valuable, an unused shopping mall in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, was a gift from his brother.

The remaining properties, consisting mostly of run-down apartments, are a mystery: He bought them all just days before handing them over, raising the question of why he could not have paid the state directly. An even bigger question is how Matraimov could have made the purchases in the first place, since his bank accounts were frozen by the court.

Matraimov and his family don’t appear to have relinquished any of the luxury properties they acquired over the years. The amount he amassed during his time in the customs service is unknown, but is widely assumed to be vast: Previous investigations revealed that he enabled and profited from customs fraud that saw over $700 million spirited out of Kyrgyzstan.

Matraimov’s compensation arrangement, reached with prosecutors behind closed doors, sets a dangerous precedent, according to Adylbek Sharshenbaev, a board member of the Kyrgyz chapter of Transparency International.

“If a corrupt person can assume that he can avoid punishment by paying a fine or through material liability [e.g. handing over property], then he can continue his activities,” Sharshenbaev said. “So in my opinion it’s categorically wrong to allow such things, that you can reach an agreement in a corruption case … Such a crime cannot be left unpunished.”

It’s unclear what will happen to Matraimov next. On February 18, he was unexpectedly detained again on suspicion of money laundering, and jailed for two months. But in Kyrgyzstan there is little faith that he will face real accountability, with one legislator even joking that his jail cell would probably be upgraded to “a cool hotel.”

Matraimov’s lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.

A Political Decision

Kyrgyzstan’s recent turmoil began in early October 2020, when citizens poured into the streets to protest a parliamentary election marred by vote-buying and other abuses. Much of the public anger was aimed at Mekenim Kyrgyzstan, a political party backed by the Matraimov family, which had won a close second place.

In the confusing days that followed, a nationalist politician named Sadyr Japarov was sprung out of prison by a mob of supporters and declared acting prime minister. Amid an uprising fueled by fury at Matraimov, he made a bold pledge to go after the famously corrupt ex-official.

“Raim-Million will go to prison,” he told a group of cheering supporters.

On October 16, as he became acting president, Japarov again repeated his promise to go after Matraimov, but this time he made no mention of prison. “Matraimov and other corruptioneers will be punished before our country with all the strictness of the law,” he said.

Four days later, Matraimov was indeed in handcuffs — only to be released that very same evening after striking a deal with investigators.

Japarov explained that a “political” decision had been reached that would allow Matraimov to avoid jail. In exchange, he agreed to admit his guilt and compensate the government for his corruption. Kyrgyzstan’s security service, the GKNB, announced that he would pay back 2 billion soms ($24 million).

Azim Azimov, a Kyrgyz political commentator, said he had mixed feelings about the arrangement.

“I’m very impressed that Matraimov paid 2 billion soms,” he said. “For the first time, he was held accountable,” Azimov said.

On the other hand, the deal felt to him like a pre-arranged sham. “Raimbek Matraimov and his organization have penetrated all the structures of power, and any punitive measures against him are quite problematic and painful [for them],” he said. “So, in coordination with each other, they made a decision that could come as close as possible to what the public expected.”

Although his fall from grace has been the subject of extensive public debate in Kyrgyzstan, what hasn’t been widely reported is that Matraimov didn’t simply pay the full sum into the treasury.

Instead, he transferred 1.4 billion soms ($17 million) in cash and paid the remaining 600 million soms ($7 million) by giving nine apartments and a shopping center to the government, GKNB head Kamchybek Tashiev announced at a December 24 press conference.

A Trial Yields More Questions

While the GKNB provided no further information, some additional details, including the addresses of the properties Matraimov gave up, were revealed during his fast-tracked trial earlier this month.

They revealed a number of irregularities.

In the first place, it’s unclear how 2 billion soms was determined to be the appropriate compensation for years of corruption. The prosecutor’s explanation involved multiplying the 16,761 trucks that had passed through a certain checkpoint during Matraimov’s time in the customs service by the amount of money he supposedly earned from each truck in bribes: $860. But this calculation yields a sum of just 1.2 billion soms ($14 million) at current exchange rates. It is unclear why other checkpoints were not mentioned and whether the amount of $860 was decided simply on Matraimov’s say-so.

Secondly, it’s unclear how the properties he gave to the government were valued at $7 million, and authorities provided no explanation. According to a representative of the State Property Management Fund who spoke in an unofficial capacity, the valuation was done by private firms and verified by authorities.

But reporters’ calculations of the properties’ total value yielded a different result. Using previous sales prices when they were known, and a range of estimates from independent realtors when they were not, the 10 properties could be worth between $5.6 and $6.7 million in total.

Finally, during the trial, the prosecutor noted that Matraimov had used his illicit profits to buy real estate — including a luxury penthouse apartment in Bishkek and a lakeside cottage. But these properties were not among those he ceded to the government.

Instead, he gave up nine apartments, some in decrepit Soviet-era buildings, and a shuttered Bishkek shopping mall. What’s more, the apartments had never before appeared among his or his family’s known holdings, and for good reason — he had acquired them in late January, just a week before handing them to the state.

When the GKNB was telling the public in December that Matraimov had already compensated Kyrgyzstan’s taxpayers by handing over the properties, he didn’t even own them.

Reporters sent the GKNB a detailed set of questions about these apparent irregularities, and received only a referral back to the court that handled Matraimov’s case. The agency did not respond to further questions.

Bishkek Apartment-Shopping

To learn more, reporters fanned out across Bishkek to investigate the apartments and their former owners.

None showed signs of occupancy. Neighbors who could be reached all said no one had lived in the properties for several months. In some cases, reporters found utility bills on the apartment doors. In fact, as they visited one apartment in western Bishkek, reporters encountered the head of the neighborhood association angrily knocking on the door. “I want to know [who lives here] too,” she said. “He doesn’t pay his bills.”

The state of the interior of the apartments could not be determined; it is not known how much money the state would have to spend to sell them or put them to another use. The State Property Management Fund did not respond to requests for comment about its plans for the properties.

Reporters were able to reach only one of the properties’ previous owners, a man named Bayastan Kelishbekov. He had sold two apartments to Matraimov on January 25.

Kelishbekov said he had dealt with an intermediary and only later discovered that the real buyer had been Matraimov after being summoned to a meeting with the GKNB. He said he had been asked not to reveal the specifics of their conversation.

Kelishbekov described the sale as fully legitimate. “We’re satisfied,” he said. “We received the sum, the initial payment, and the rest of the installments according to the contract.” He did not disclose the amount Matraimov had paid, citing confidentiality.

In only one case did an apartment’s previous owner have any visible connection to Matraimov: The name listed in one of the property records is that of his nephew, Nurseit Sydykov.

Scroll through the gallery below to see what reporters found in each of Matraimov's apartments:

The largest property Matraimov handed over to the government, the Eldorado shopping center, had previously been reported to belong to his family — an apparent windfall from the very same corrupt scheme he had just pleaded guilty to operating. He received the shuttered mall from his brother just days before giving it up.

The Saga of Eldorado

Raimbek’s sister-in-law, Minavar Zhumaeva, had acquired her 50 percent stake in Eldorado from the Abdukadyr family — Raimbek Matraimov’s partners in the underground smuggling empire that ran with his patronage during his time in the customs service.

The government’s decision to accept property from Matraimov instead of cash is troubling for its lack of transparency, said Sharshenbaev, the TI board member. “The general practice is that, if there are funds, then these judicial fees should be paid in money. And only in the case that it’s impossible to collect money does the government collect in the form of real estate or other property.”

“If you’re using real estate, the citizens can lose trust [in the process] in terms of who’s evaluating this property,” he added. “This also leads to a loss of trust in the authorities, if there’s a suspicion that the property has been overvalued.”

Arrested Again

In exchange for agreeing to cooperate with the investigation, admitting his guilt, and paying the 2 billion som compensation, Matraimov was released and the freezing orders on his and his wife’s properties and bank accounts were lifted. He was sentenced to pay a fine of just 260,000 soms ($3,080).

But his release stoked growing public outrage and even a small protest in Bishkek. Afterwards, the GKNB announced that it was still investigating his foreign properties. Three days later, on February 18, Matraimov was arrested again on suspicion of money laundering and ordered to be kept behind bars for two months as the investigation continues.

His supporters, who recently held a march to call for his release, are now portraying Matraimov as a victim who has paid his dues to the state.

Elnura Alkanova, a former journalist and Matraimov supporter, said that he had struggled to come up with the money to pay the government his 2-billion-som reimbursement. “Part is his family’s money, part is money from his relatives, his supporters, people with whom he has a good relationship,” she said. “He sold all his property that he had, he sold his cattle, he gave all of this up.”

However, land records obtained by reporters show that none of the many Kyrgyz properties held by Matraimov, his family members, or his close associates had changed hands in recent months. It is unknown whether his wife still retains the family’s luxurious Dubai penthouse.

This is precisely why transparency is important, advocates say.

“This should all happen in the open,” said Sharshenbaev, the Transparency International board member. “The public should know what steps are being taken. Everything should be covered in the media.”

"[Otherwise] it’s a signal to the corruptioneers — ‘Go ahead and steal, share a bit, and then you can go free.’"

President Japarov’s administration did not respond to requests for comment.