A decade ago, Regina Marcenkiene was a broke university graduate scrounging up work where she could get it, so when a friend introduced her to a woman named Anastassia who needed a logo and branding materials for a new company, she jumped at the opportunity.

Anastassia briefed her in a short email on March 6, 2010: “Named Beta Consulting, the company provides consulting services on taxation, as well as on savings and investment. Target audience - businessmen, wealthy individuals. Mostly Russian speakers from different countries.”

Nothing seemed amiss with the request, and Regina delivered in a week, even adding her own name to the invoice templates to make the design look more realistic — a small decision that would come back to haunt her. Anastassia was satisfied with the work and paid her the agreed fee, 64 euros.

Regina thought that was the end of the assignment — until her 64-euro commission earned her a place in one of the world’s biggest-ever money laundering cases.

What she didn’t know, until police got in touch with her last autumn, was that Anastassia was the wife of Juri Kidjajev, head of a unit at Danske Bank Estonia that catered to foreign customers, and that Beta wasn’t just an Estonian tax consultant.

In fact, there is no indication that the firm ever did tax consulting. Instead, it was registered in the Marshall Islands and served as one of the main shell companies used by the bankers of Kidjajev’s unit to help their clients launder money.

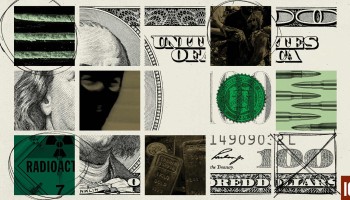

Danske Bank was hit by one of the world's largest ever money laundering scandals in 2017, when a team led by Danish newspaper Berlingske and OCCRP first uncovered how billions of dollars of dirty money were funneled through the institution’s Estonian branch.

A report ordered by the bank found that it had handled $234 billion in offshore transactions, many of them suspicious. Much of this was enabled by the division in Estonia that dealt with foreign clients from countries like Russia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine.

After being approached by reporters for comment in 2017, the bank publicly apologized for allowing the illicit payments, describing the affair as “unfortunately yet another example showing that we failed to prevent our being exploited for money laundering.”

About This Investigation:

The FinCEN Files is a 16-month-long investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, BuzzFeed News and more than 400 international journalists in 88 countries, including those from OCCRP and its network of member centers.

But now, a leak of criminal investigation documents, obtained by Italian news magazine L’Espresso and shared with ICIJ and OCCRP, shows the bank was far more than merely negligent. A team of 11 bankers at Danske’s Estonian branch were actively helping their elite clients skirt anti-money laundering regulations by running offshore companies for them.

In turn, the bankers — or “relationship managers,” as they were known within the unit — were leading lavish lifestyles: driving sports cars paid for in cash, collecting luxury jewelry, and receiving large personal loans from clients that never came due.

Taken as a whole, the new leak of emails shows how the corruption of a small team was enough to turn a large Western bank into a laundromat that cleaned dirty money from Eastern European countries.

Danske Bank declined to reply to specific questions on this story, but sent a general statement admitting that it was clear that the bank should have never had its portfolio of non-resident customers.

“It is also clear that we were too slow in realising the extent of the issues and to close it down,” the statement said.

‘Collusion to launder money’

Beta Consult Corp, run by the bankers on the team using private email addresses and sometimes working through family members, was central to the effort. It was registered in the Marshall Islands but held an account at Danske Bank Estonia, with many different shell companies paying in.

The company was nominally owned by a Ukrainian man, but he told OCCRP that he had never heard of it. Instead, the leaked emails show, it was Juri Kidjajev who received monthly reports on Beta Consult’s revenue, including which companies paid it and which of his team members had facilitated the transactions.

Although OCCRP only managed to obtain fragmentary information on how much money passed through the company’s accounts, one report sent to Kidjajev’s personal email address indicates that Beta took in over $150,000 in a single month, September 2012, from customers including AvroMed Company LLP, a British company that was a major recipient of Azerbaijani Laundromat funds.

ICIJ and OCCRP found additional evidence of Beta Consult having received $128,635 in payments, most of it from three companies at the heart of the Azerbaijani Laundromat: Inmaxo Capital Corp, LCM Alliance LLP, and Metastar Invest LLP.

Although OCCRP has written extensively about how these companies operated, the newly leaked material reveals that Metastar Invest was, in fact, sold by the bankers of Kidjajev’s unit to their clients.

Metastar seems to have been established through Swiss Registry Consulting, a formation agent operating in several European countries that specialized in creating and selling offshore companies to clients around the world. Emails between Swiss Registry Consulting and the Danske Bank staff — all using private addresses — show how they sold around a dozen offshore companies in a three-month period in 2009.

In one email, Kidjajev referred to his bankers as a team that worked together to sell companies off the “shelf,” as he put it.

“Aleks, hi!” he wrote in Russian to the formation agent. “As far as I understand, we (our shelf) sold 13 companies over the last three months. Or is that not so?”

Graham Barrow, an expert in anti-money laundering issues who has worked for banks such as HSBC and Deutsche Bank, told OCCRP that bankers selling their clients offshore companies is a major red flag.

“That is effectively collusion to launder money,” he said.

“In order for a bank to conduct effective and robust due diligence, it needs to maintain independence from its customers. Enabling them to create complex and secretive ownership structures runs counter to that requirement and could prejudice any future suspicions as the bank itself would, by extension, be implicated.”

In another email, sent in January 2010, a Swiss Registry representative sent Kidjajev a new price list for company formation services. Most options were for companies in offshore jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Belize, and Marshall Islands. But the most expensive item on the list, at 4,750 euros, was closer to home: the formation of a Danish limited partnership, known as a “K/S.”

“A comfortable jurisdiction to open a bank account at Danske Bank,” read a comment next to the offering.

A leaked email sent by another banker now under criminal investigation, Jelena Makarova, provides a glimpse into how the team operated.

Makarova explained that each relationship manager would be assigned a personal code number that they could add to the invoice numbers submitted by Beta Consult to Azeri Laundromat companies and other “customers.”

They included Goldcraft Universal, a firm that investigators believe was used to launder embezzled money from Georgia.

The Goldcraft Saga

In 2008, the man who headed Danske Estonia’s non-resident unit at the time, Erik Lidmets, personally approved the documents to open an account for a company called Goldcraft Universal LLP, supposedly based in Odessa, Ukraine. An elderly Serbian man, Zivojin Nikolic, was marked in the bank’s database as the beneficial owner.

This system of assigning personal code numbers to use on invoices would allow the unit to easily keep track of which banker sold which services to whom.

Mihhail Murnikov, one of the bankers in the unit, is now under investigation in both Estonia and Latvia, where officials have seized more than $2 million euros from a bank account he opened.

He told Estonian investigators that Juri Kidjajev and another colleague, Anna Kurilenko, were considered Danske Bank Estonia’s “gateway” for nonresident clients. Kurilenko had Beta Consult Corp — the Marshall Islands-registered firm at the center of the money laundering scheme — in her own portfolio, though she told investigators she didn’t remember how it became her client.

Danske agents would scout for new clients in Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Kazakhstan, then send the information to Kidjajev and Kurilenko.

“Anna and Juri forwarded the info to us [relationship managers], [asking] who wanted the client. If anyone wanted them, then relationship managers contacted the new client and took things over,” Murnikov said, according to a transcript of his interview with Estonian investigators.

Then, the banker would help the client prepare documents needed to pass the bank’s anti-money laundering checks. The final go-ahead to accept a new foreign client was given by a committee whose members included Danske Estonia’s CEO, the bank’s head of compliance — and Juri Kidjajev himself.

In an email sent on March 19, 2010, right after Marcenkiene had finished her graphic design work, Kidjajev sent the bankers the fruits of her labor: new Beta Consult business cards, templates for PowerPoint presentations, and an updated invoice template that featured Beta’s new logo.

“I ask you to use the new forms with Beta insignia when invoicing,” Kidjajev advised the recipients.

In early January 2014, a woman named Anna wrote from a general Beta Consult email address to the Danske bankers’ private email addresses saying that “starting from January 8 all offshore related matters will be curated by Olga.”

When OCCRP called the phone number given in the email, the call was answered by Olga Tšetverikova, another Danske banker from the same division who is now under suspicion in the criminal case. She claimed she didn’t know anything about Beta Consult and found an excuse to end the call.

“Let’s take a look out of the window to see what’s the weather today. It is beautiful, everything is okay. Excuse me, I need to go,” she said.

Beta Consult was also used by the Danske bankers as a conduit for selling offshore companies to clients.

One of these new offshores, Solidstar Worldwide LLP, transferred a total of around $23 million into the Azerbaijani Laundromat after being sold by the bankers. It was registered in the UK as a partnership of two companies from Belize, making it almost impossible to determine who was behind it.

Internal documents name the salesperson as Marcenkiene, the student who was paid 64 euros to create Beta’s branding materials.

“No, no, no,” Marcenkiene answered when asked by OCCRP if she had actually been involved in selling offshores through Beta. She said she had never heard of Solidstar Worldwide and never worked for Beta Consult.

There were other invoices bearing her name, too, making it look like she had sold multiple companies to offshore clients.

“Why would they use my name without even asking me about it?”

Cars, Watches, and Gold

The banker who actually did sell Solidstar Worldwide was Jevgeni Agnevštšikov, one of the most successful “relationship managers” making cash flow into Beta Consult’s accounts, an analysis of the invoice codes reveals.

When Estonian investigators questioned Agnevštšikov in January 2019 about his involvement in alleged money laundering, he blamed Danske Bank for overloading the relationship managers with work and having poor technical systems, making it hard for him to keep track of everything.

“At times my client portfolio might have even had 350-400 clients when normally bank employees with such functions have roughly 100 clients,” he said.

But the leaked Estonian police files suggest he was not just a passive victim of overwork.

In 2015, shortly after leaving Danske Bank, he made two large cash deposits into his accounts. The first one was 23,850 euros, followed by 120,000 euros seven months later. Agnevštšikov claimed the funds were a loan from a Ukrainian man named Igor Kolosnitsyn, which he used to buy an apartment in Tallinn and to start a new company.

A man named Igor Kolosnitsyn was also the beneficial owner of three companies in Agnevštšikov’s portfolio of accounts.

Who Is Igor Kolosnitsyn?

Kolosnitsyn’s father, Aleksandr, was once the CEO of St. Petersburg’s major seaport, Petrolesport. The younger Kolosnitsyn is the owner of Bank Portal, one of Ukraine’s newest banks, founded in 2013. In March 2020, Ukraine’s Supreme Court upheld a 2017 decision to fine Bank Portal for “high-risk behavior regarding financial monitoring.”

“That is a massive conflict of interest. You can't have a financial relationship with a customer,” said Barrow, the anti-money laundering expert. “Your first responsibility should be to the bank and its legal requirements.”

Even accepting a loan from a client after leaving a bank usually constitutes a breach of ethics, Barrow said.

“When a relationship manager leaves a bank, there are often ‘handcuff’ clauses that prevent them from approaching or doing business with former clients,” he said. “Whilst we simply don’t know if this is the case here, it looks bad when you see a former employee receiving a loan from an individual who used to be a client.”

A transcript of a police interview with Agnevštšikov, obtained by l’Espresso, reveals that the banker led a lavish lifestyle that did not seem commensurate with his income.

At the time, take-home pay for a relationship manager at a bank like Danske would have averaged around 2,000 euros per month, the former CEO of a Scandinavian bank’s Estonian branch told OCCRP.

But Agnevštšikov drove a 50,000-euro Range Rover Sport that he paid for in cash. He said he had received this money from Russia, but declined to reveal who sent it. His wife also bought a BMW x5 in cash, a purchase Agnevštšikov struggled to explain to investigators. He claimed that another car registered in his name, a Mercedes Benz GL 320 worth around 20,000 euros, had been collateral for a 500-euro loan to a friend.

Police also found a trove of jewellery and watches at his home from luxury brands including Tag Heuer, Longines, Tissot, and Tiffany’s, as well as Swiss gold plates. He also could not explain where he had obtained the money to buy these.

When the Estonian Financial Supervisory Authority forced Danske Bank to close its non-resident unit in 2015, Agnevštšikov set up a private investment consultancy firm together with two other ex-Danske bankers from the unit. All are now being investigated for money laundering.

Fast Cars and Big Loans

Agnevštšikov was not the only banker at Danske’s Estonia branch to have been inappropriately entwined with his customers — or to have prospered from his association with the bank.

Kidjajev’s predecessor as head of the international and private banking unit was Erik Lidmets, a round-faced man nearing 50 with a passion for vintage cars. His collection has included a 1953 Jaguar and a Porsche 911 built in 1972. In 2013, an Estonian business daily estimated that his net worth was 9.6 million euros.

He was also the lucky shareholder of an Estonian firm, Eridan, which received huge loans from his own Danske Bank clients over the years — including one company, Goldcraft, that was receiving millions of dollars in embezzled funds from Georgia during the same period.

Estonian police suspect these payments were made to reward Lidmets for opening a bank account for Goldcraft and covering up its true beneficiary.

Passing Around Eridan

Although the ownership of OÜ Eridan DVL was buried under layers of offshore secrecy, those who ultimately benefited from it were all connected to the Danske Bank offshore team.

Eridan received a total of $500,000 from Goldcraft in four installments. The transaction descriptions claim the money was being paid out for a credit agreement, but OCCRP could find no evidence in Eridan’s financial statements that it ever repaid the loan.

By 2009, Eridan had also received over 1.7 million euros in loans from Korberg LP, another company that banked with Danske and supposedly belonged to Zivojin Nikolic, the same elderly Serb who was nominally the beneficiary of Goldcraft.

According to an OCCRP analysis of Eridan’s accounts, these loans were used to buy and renovate two houses in Tallinn. One of them, in a hip district of the Estonian capital, was rented out the following month at a bargain-basement price to a gym and wellness center belonging to the wife of Lidmets, the man who had headed Danske’s international and private banking unit before being fired.

Eridan received just over 10,000 euros a year in rental fees from both buildings, meaning the gym would have been paying rent far below the normal market rate.

“There are so many red flags here that should make every seasoned financial crime investigator really attentive,” said Norman Aas, an Estonian lawyer who served as the country’s prosecutor general from 2005 to 2014, after OCCRP asked him to review the documents.

Extending loans and never asking for repayment “is not a usual practice,” Aas said.

Even more unusually, in 2010 Korberg LP cancelled nearly 350,000 euros’ worth of its loan to Eridan. Although records show that Korberg was dissolved in 2010, Eridan reported that the company had cancelled another 1 million euros of loans in 2011 and 2012.

Lidmets hung up on an OCCRP reporter and did not answer subsequent calls and an email with specific questions. “Thank you for your letter. Unfortunately, due to an ongoing criminal investigation, I can’t give any comments,” he replied to a text message.

His successor, Juri Kidjajev, was also living well — even after he was detained for questioning in 2018 over the Danske Bank scandal.

He had taken up a similar post at another bank, Citadele, a successor to Latvia’s Parex Banka, after Danske was forced to shut down. When news broke out that he had been detained for questioning in the Danske criminal investigation, Citadele fired him.

Still, he and his wife live in a home that is expensive by Tallinn standards, with 300 square meters of floor space, a wine cellar, a sauna, and a private cinema in the basement, worth around 480,000 euros. Estonian investigators are looking into whether the house was purchased using the proceeds of a bribe he received during his time at Citadele.

Kidjajev didn’t reply to phone calls and emails from OCCRP journalists seeking comment.

Kurilenko, the banker on Kidjajev’s team who allegedly served as a “gateway” for nonresident clients, was also questioned by Estonian investigators over the large amount of wealth she had accumulated during her time at the bank, including 338,686 euros in cash she deposited into a bank account between 2011 and 2018, a BMW 525D XDRIVE, and a large amount of jewelry.

When Estonian investigators asked Kurilenko where the cash had come from, she said she could not remember, as it had been such a long time since she received it.

“But definitely the money is not from crimes,” she said.