Reported by

A cyberattack on several Brazilian ministries in July was carried out by a new gang known as Fog, named after the ransomware it uses, according to the group’s darknet page and law enforcement documents obtained by OCCRP.

Like other ransomware groups, Fog operates in the so-called “darknet,” an online space where criminals deal in drugs, weapons and other illicit items and services.

Fog’s darknet page is not accessible through a simple search. However, its URL address was included in a report by the Federal Police of Brazil, which reporters obtained.

The darknet page included a link to a secure chat that reporters accessed using a password found in the police report. The archived chat revealed information about Fog’s July 23 hack of nine Brazilian ministries, the nation’s mint, and its anti-money laundering agency.

A ransom note left for Brazilian officials in a “ReadMe” file stated: "If you are reading this, then you have been the victim of a cyberattack. We call ourselves Fog and take full responsibility for this incident."

The cyber-gang demanded $1.2 million to decrypt the files.

A Brazilian government team found that at least 28 gigabytes of data were sent by the attackers to two external servers in the U.S. This triggered legal cooperation between U.S. and Brazilian authorities investigating the hack.

OCCRP obtained emails exchanged between Brazil's Ministry of Justice and the U.S. Department of Justice, which shed light on the ongoing joint investigation into the “hacker group FOG.”

Brazil formally requested U.S. assistance to access data stored on four virtual machines linked to the origin of the attack, which could help uncover the identities of those responsible for hacking the government’s system.

The Federal Police of Brazil declined to comment because the investigation is ongoing, while the justice ministry did not reply to questions.

It is unclear if Brazilian authorities paid a ransom to retrieve the files stolen by Fog. The communications reporters reviewed between authorities and the ransomware group do not suggest any payment was made.

Lost in the Fog

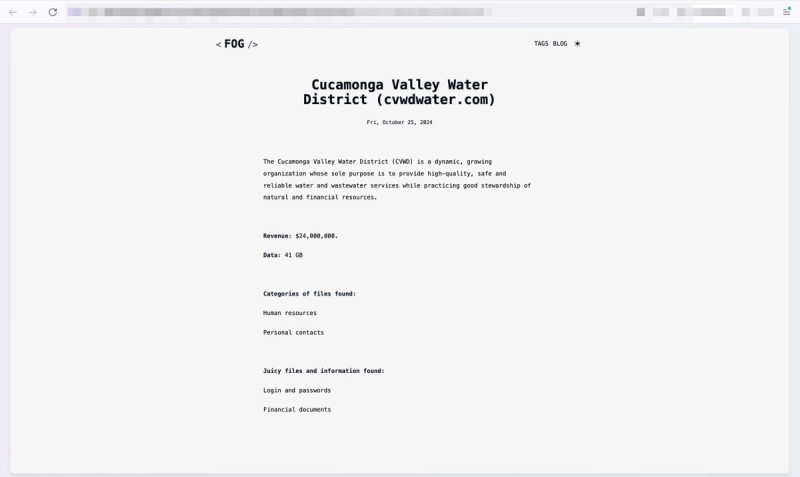

Fog’s page on the darknet includes blog posts that note the day they were published, as well as names and summaries of hacking victims, and the ransom demanded for the stolen data.

Posts also cite the size of the files in the group’s possession, categories of documents obtained, and details on sensitive or relevant information.

Screenshot of the Fog group’s page with the ransom demand for the stolen data.

According to its page, the Fog group hacked 58 entities, in addition to the Brazilian targets, between June 19 and November 27. Over 70 percent of those attacks targeted U.S.-based institutions, but Fog has also hit entities in a dozen other countries, including Australia, Germany, and Canada.

The group did not blog about the Brazilian attack. However, the ransom note that Fog left for Brazilian negotiators on its darknet page included a second link and a login password for a private chat, which reporters were able to see.

On July 27, four days after the systems of nine ministries and two agencies were breached, a message was sent in this private chat. A person who apparently worked with one of the Brazilian government bodies responded by saying "hi" in English.

Someone replied about 40 minutes later, saying: "You will receive the details soon."

Five hours after that, Fog shared a file named "economia listing.txt" and added: "That’s what’s been taken.”

On July 29th, Fog wrote: “We can decrypt your systems in a couple of hours for only $1,200,000."

Fog listed 1,087 files it had hacked, amounting to approximately 29 gigabytes of data. Among the file types were formats such as “.qvd” and “.csv,” which are commonly used for statistical and financial analyses.

While reporters could see the file names, they were unable to access the contents.

However, the names of some files — such as "beneficiarios_especiais.qvd" (special_beneficiaries.qvd), "dados_bancarios_cultura_LPG.qvd" (bank_data_culture_LPG.qvd), and "usuarios_conc_siconv.qvd" (users_conc_siconv.qvd) — suggest that they include confidential information, such as bank data, names, and other personal identifiers.

The list also revealed files that could contain sensitive data, such as user information and access records to government systems. There are references to platforms like Siconv, which manage systems for agreements and federal transfers. Also referenced was Dataprev, the entity that processes social security data for the government.

Files referencing Siconv and Dataprev — including "usuarios_conc_siconv.qvd," "novo-usuarios-painel-siconv.xlsx," and "usuarios_dataprev.qvd" — raise concerns about the potential exposure of credentials or public employee information.

‘Forming a Ransomware Gang’

Last June, Arctic Wolf, a global provider of cybersecurity solutions, published a blog post reporting the discovery of “a new ransomware variant referred to as Fog.”

In a response to questions from reporters, Arctic Wolf said a criminal group appears to have taken on the name of the ransomware.

“This indicates the evolution of threat actors, moving from launching a variant to forming a ransomware gang,” Arctic Wolf said in an email.

At the time of its blog post, Arctic Wolf said all victims of the Fog ransomware were in the U.S., with 80 percent of them in the education sector.

But OCCRP’s findings show that Fog ransomware has since been used in a broader range of attacks. Three out of every 10 attacks were aimed at an institution outside the U.S., while only 22 percent were linked to the education sector.

In the case of the July attack, Brazil's cybersecurity team identified familiar signs of the Fog group’s prior activities, according to correspondence authorities investigating the incident.

These included the compromise of credentials for Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), which allow users to hide their locations and more securely browse the internet.

The Fog group used VPNs provided by four U.S.-based companies to breach the Brazilian government systems. Cybercriminals often use VPNs and cloud servers to mask their location, making it difficult to trace them.

Brazilian investigators requested data preservation from the four U.S. companies hosting the remote access systems used in the July 23 attacks. The Federal Police report obtained by OCCRP shows that three VPN providers are processing the requests from law enforcement, while another has yet to be contacted.

This request “is critical in cyber investigations, as it allows authorities to obtain essential evidence to identify and hold the perpetrators accountable,” according to Solano de Camargo, president of the Privacy, Data Protection and Artificial Intelligence Commission at the São Paulo Bar Association.

“Internet and hosting service providers have limited liability and are not held responsible for content generated by third parties, provided they do not directly engage in illegal activities and comply with legal and judicial orders,” he added.

The data preservation request was made via the 24/7 Network of the Organization of American States, which facilitates cooperation among countries in cases of cybercrime, correspondence between Brazilian and U.S. authorities shows.

However, De Camargo said that data preservation by foreign companies “poses significant challenges, such as legal differences between jurisdictions, sovereignty issues, and the need for international legal cooperation agreements.”

Brazil considers the case "sensitive, a priority, and urgent," according to one of an email obtained by reporters.

The email communications between Brazilian and U.S. authorities show that cybercriminals breached Brazilian government systems, and encrypted the data they targeted. The attackers also paralyzed a key platform used by federal government employees to exchange internal documents.

After gaining access to the government environment using valid VPN credentials, the attackers began a process known as "credential dumping" to collect more login details, allowing them to move between servers disguised as legitimate users.

The hackers also targeted a backup server that stored administrative-level credentials, enabling them to control and encrypt virtual machines hosting public services, according to correspondence between Brazilian and U.S. authorities.

Encryption is a technique that scrambles a victim’s data, rendering it inaccessible without a decryption key, which is usually demanded in exchange for a ransom, explained Lucas Lago, of the Aaron Swartz Institute, a Brazilian non-profit that advocates for digital rights.

Outdated Legislation

If Brazilian investigators manage to identify the ransomware attackers, the culprits will be tried in Brazilian courts under extortion laws passed in 1940. Two Brazilian Congressional commissions are reviewing two separate proposals to update legislation to make it more effective against cybercrime.

Senator Carlos Viana, a rapporteur of one of the two legislative proposals to address this gap, told OCCRP: “The main goal of the project is to update and adapt the law to our current reality, where interactions are often exclusively digital.”

Viana emphasized that “protecting public information, especially those involving people's data and available resources, is fundamental within our project, and current legislation does not properly address this.”

In the other legislative proposal, Senator Angelo Coronel advocates creating a specific legal category for digital extortion or data ransom crimes. Coronel argues in his proposal that digital extortion has distinct characteristics from traditional situations, and requires specific provisions in the criminal code.

Viana agreed that the current legislation is outdated.

“It treats extortion crimes with the same parameters of the 20th century,” he said.

Kevin Hall (OCCRP), and Felipe Payão (TecMundo) contributed reporting.