This July, the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, a partner of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), published a video recorded by an officer in a prison colony near Yaroslavl in central Russia. It showed an inmate being tortured.

The man is tied up, spread-eagle, on a table. One by one, people wearing camouflage uniforms beat him on the legs and heels with rubber truncheons. The man howls and begs for mercy. From time to time, the men pour water on his head from a bucket.

That’s how officers in a Russian prison conducted what one of them described as “educational work” with a convict. After the video was published and viewed by several million people, 12 employees of the Federal Prison Service (abbreviated FSIN in Russian) were arrested on charges of abuse of authority with the use of violence.

Based on judgments last year by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), Russia was implicated in over half of cases involving torture, inhuman treatment or ineffective investigation of such crimes.

Now, Novaya Gazeta has analyzed data from two of the largest Russian databases of cases like these. Though not every judicial decision is publicly available, the data detail almost 4,500 sentences handed to officials. Many abusers receive suspended sentences and are able to return to their duties in just a few years. And the compensation victims receive is often dozens of times less than requested.

One group that is not complained about much are the various branches of Russian intelligence. The data show no sentences handed out to FSB officers at all.

A screenshot from a video taken in a Yaroslavl Prison Colony, showing an inmate being tortured.

A screenshot from a video taken in a Yaroslavl Prison Colony, showing an inmate being tortured.

Russia told the UN Committee Against Torture that the case in Yaroslavl was an exception. The convict had intentionally provoked the guards, senior FSIN officials said.

But a month later, Novaya Gazeta published a video that showed another beating in the same prison. This time, FSIN employees forced inmates to run along a corridor as they beat them with their bare hands and truncheons. Then the prisoners were taken to a separate room, without a camera, followed by a crowd of jailers. One holds a bedsheet. In the previous video, a sheet was used to muffle the victim’s screams.

Evidence shows the use of violence by Russian officials isn’t confined to just a few “provocateurs,” and it’s certainly not limited to one prison. In the last six months, Russian media outlets and human rights organizations reported over fifty torture cases. But these reports rarely lead to trials. Moreover, since the Russian penal code contains no specific article banning torture by officials, those cases that are brought to court are usually classified under part three of Article 286: “Improper exercise of authority with the use of violence or weapons or with infliction of injury.”

The Dataset

There are a few caveats: Any individual case can include from one to several people, so the number of cases doesn’t equal the number of convicted officials. Not just violence, but also other crimes ( such as causing a major accident, lengthy stoppage of transport or of a production process, or causing significant material damage) are also included. These cases were excluded from the analysis.

Finally, the vast majority of judicial verdicts in Russia are guilty — over 99 percent in 2017.

To gather a fuller picture of who is tried for this crime in Russia and how, reporters analyzed all the available sentences handed down on this charge from 2011 to 2017.

The analysis enabled reporters to reach some conclusions about the extent of violent official abuses of power in Russia, actions which, according to the UN, should be classified as torture.

The problem isn’t limited to the army, prisons, or police stations; it also occurs in other state institutions.

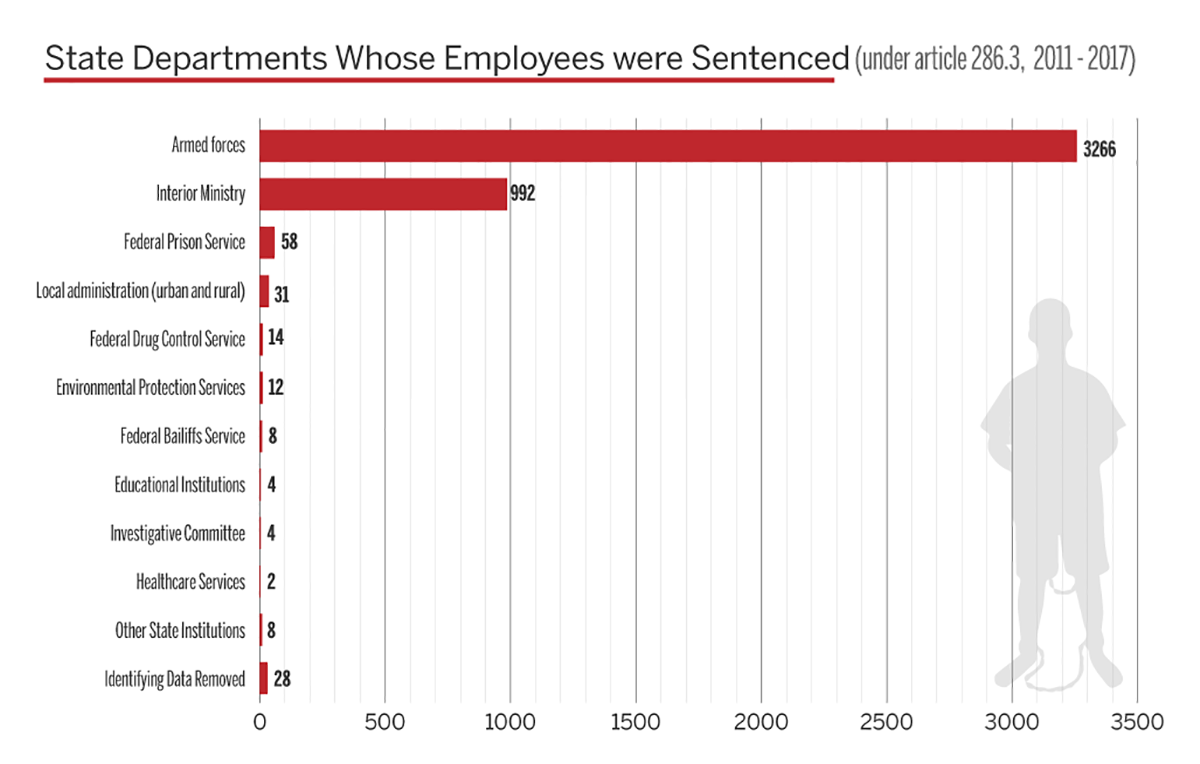

The Full Count

Most of the sentences for acting as an official abuser of power with violence (over 3,200) were handed down to military personnel. The majority stem from hazing, an issue widely covered by domestic media.

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

In Vladikavkaz in 2012 for example, the court found conscript Sergei Shestakov guilty of violence against another soldier who refused an order to clean up a tent. According to the court, Shestakov struck the victim on the back of the head with his palm, causing “closed craniocerebral trauma with a brain contusion in the left hemisphere [and] hemorrhages under the hard and soft medulla.” The soldier died in the military hospital of the Vladikavkaz garrison. The court sentenced Shestakov to one year in prison and deprived him of the right to hold any official position for two years.

Such cases have also led to psychological damage among soldiers and, in some instances, suicide.

The Mother’s Right Foundation, a non-government human rights organization, provided legal aid to 2,209 families of soldiers who died in the army. According to the families receiving the assistance, more than one third of these cases involved soldiers who committed suicide in 2017.

Interior Ministry officials have been responsible for the second-greatest number of cases in the data analysed: over 900 in seven years.

Sergey Babinets, a lawyer of the Russian Committee Against Torture, a non-profit watchdog, said it’s hard to draw conclusions about torture from official statistics. “It’s easier to complain about a policeman than a prison warden. It’s also easier to bring a case against a police officer to trial,” he said.

According to the data, officers of the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) are responsible for the third-largest number of sentences for torture, despite the fact that torture in prisons is frequently reported in the media. Reporters found 65 cases where FSIN officials were convicted and 58 cases where they were sentenced.

However, these numbers may prove the data isn’t complete. The Russian Committee Against Torture received 2.5 times more complaints about torture — 169 — in prisons over the same time period. A much larger number are likely never reported.

A man walks through a corridor at the Kresy-2 Detention Center outside St. Petersburg, one of the largest prisons in Europe. Credit: Alexander Demianchuk / Reuters

A man walks through a corridor at the Kresy-2 Detention Center outside St. Petersburg, one of the largest prisons in Europe. Credit: Alexander Demianchuk / Reuters

The fact is that authorities are less willing to investigate complaints against prison officials, Babinets said.

There’s another reason these numbers don’t capture the full extent of torture in Russian correctional facilities. It’s been reported that FSIN officials sometimes involve other prisoners in committing torture. In one case, it was reported that the acting deputy head of the Ulyanovsk Prison Colony #8, Dmitry Kazakov, allowed his subordinates to let three prisoners into the exercise yard of the punishment isolation unit. They beat up another prisoner who later died from his injuries. The court did not determine that Kazakov had done this with the intent of having the beating take place, but still found him guilty of abuse of authority.

With respect to the absence of cases involving Russian intelligence branches, Babinets said that his organization receives complaints about the FSB only rarely, just 18 times between 2011 and 2017. It has been impossible to bring any of them to justice or even to hold any effective investigations, he said.

Deaths, Suicides and Prison Violence

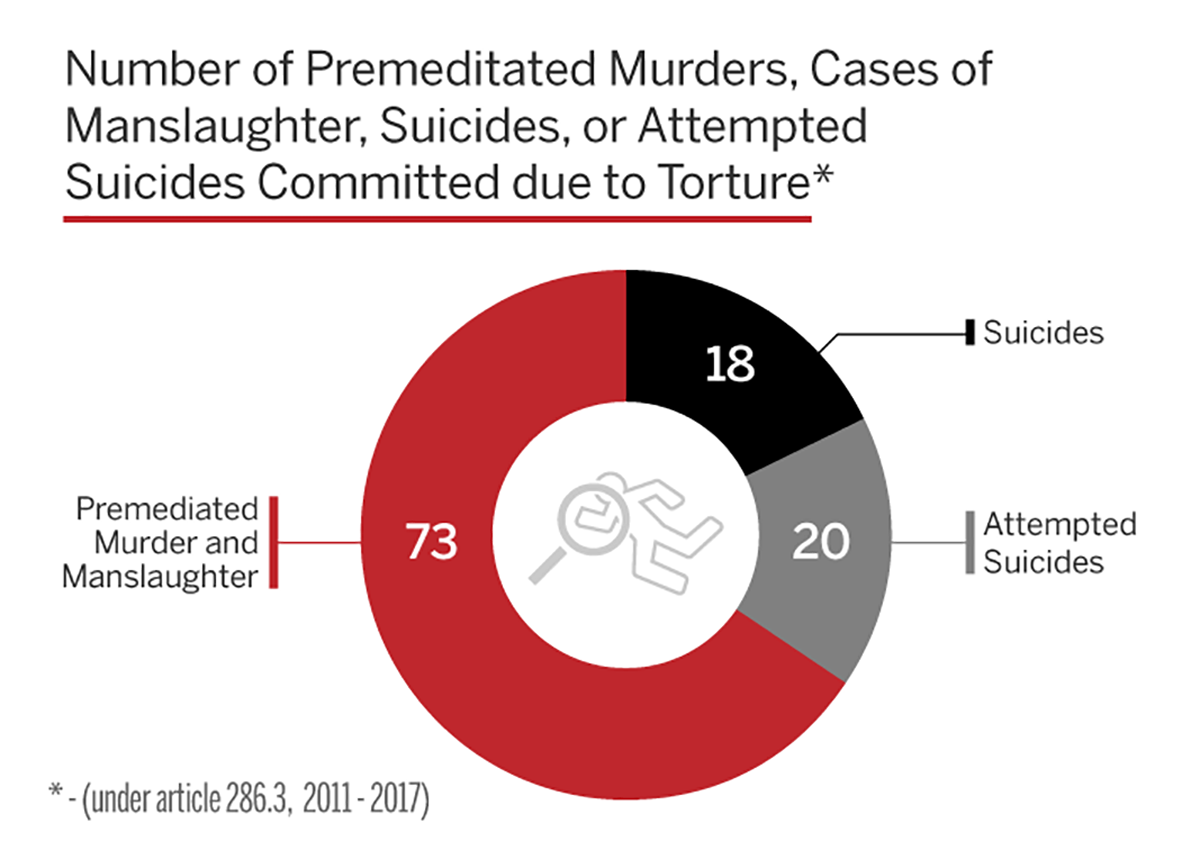

In addition to causing physical and moral harm, there were 111 cases in which the abuse led to intentional or unintentional killings (73 cases), suicides (18 cases), or suicide attempts (20 cases).

Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

A majority of the killings — 44 cases — were committed by interior ministry officials, followed by military personnel with 17, and FSIN officials with 8.

The suicides were most often a result of actions by military personnel and interior ministry officials. They are also responsible for the majority of suicide attempts: 13 cases happened under the watch of the interior ministry and six under the military.

Because violence in correctional facilities has been so widely covered in Russia this year, reporters conducted further analysis in this sector to discover the extent to which perpetrators faced justice.

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

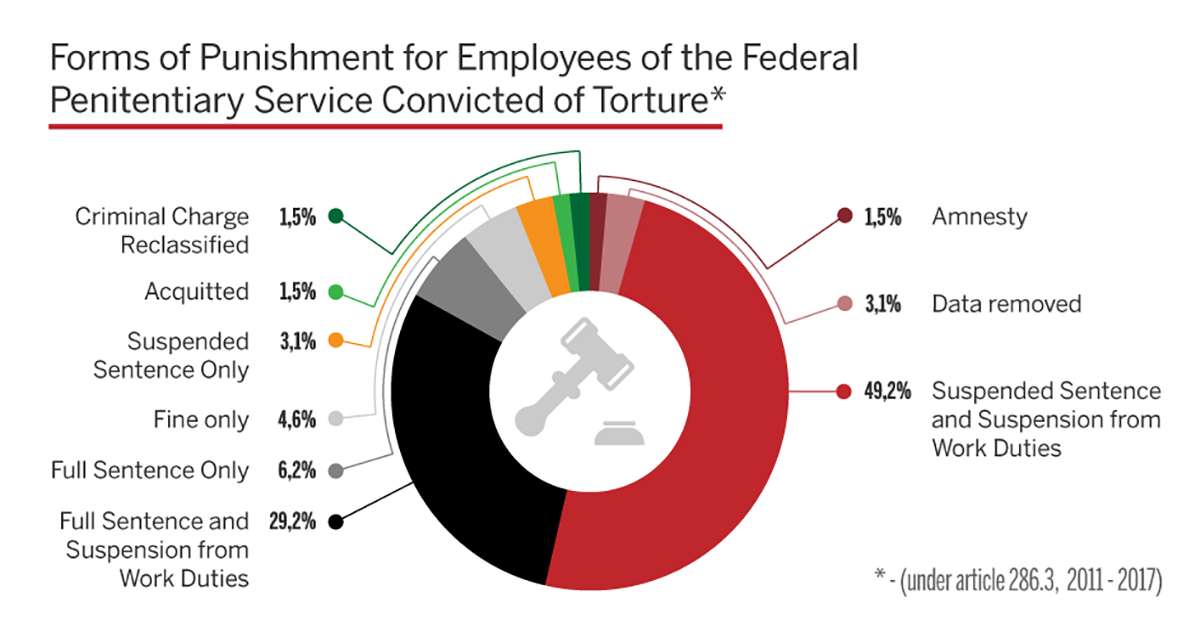

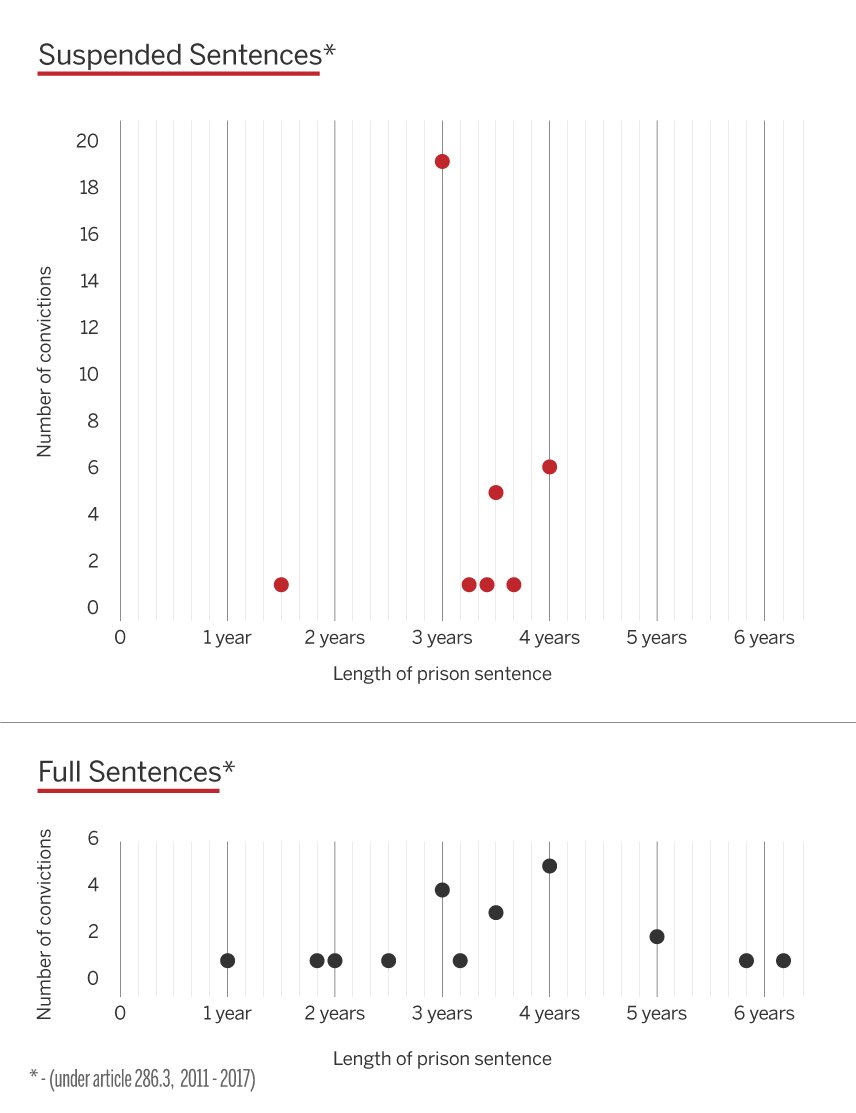

Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP In half the cases involving FSIN officials, those sentenced for torture avoided real punishment. Instead, the courts tended to impose suspended sentences of up to four years and banned officials from holding certain positions for one to three years. FSIN officials were ordered to serve real prison time in only about one third of the cases.

Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP In half the cases involving FSIN officials, those sentenced for torture avoided real punishment. Instead, the courts tended to impose suspended sentences of up to four years and banned officials from holding certain positions for one to three years. FSIN officials were ordered to serve real prison time in only about one third of the cases.

According to the Committee Against Torture, most complaints about torture accuse officials with the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In Russia, this includes police officers as well as detectives, criminal investigators, other law enforcement officials.

Compensation Is Often Slashed

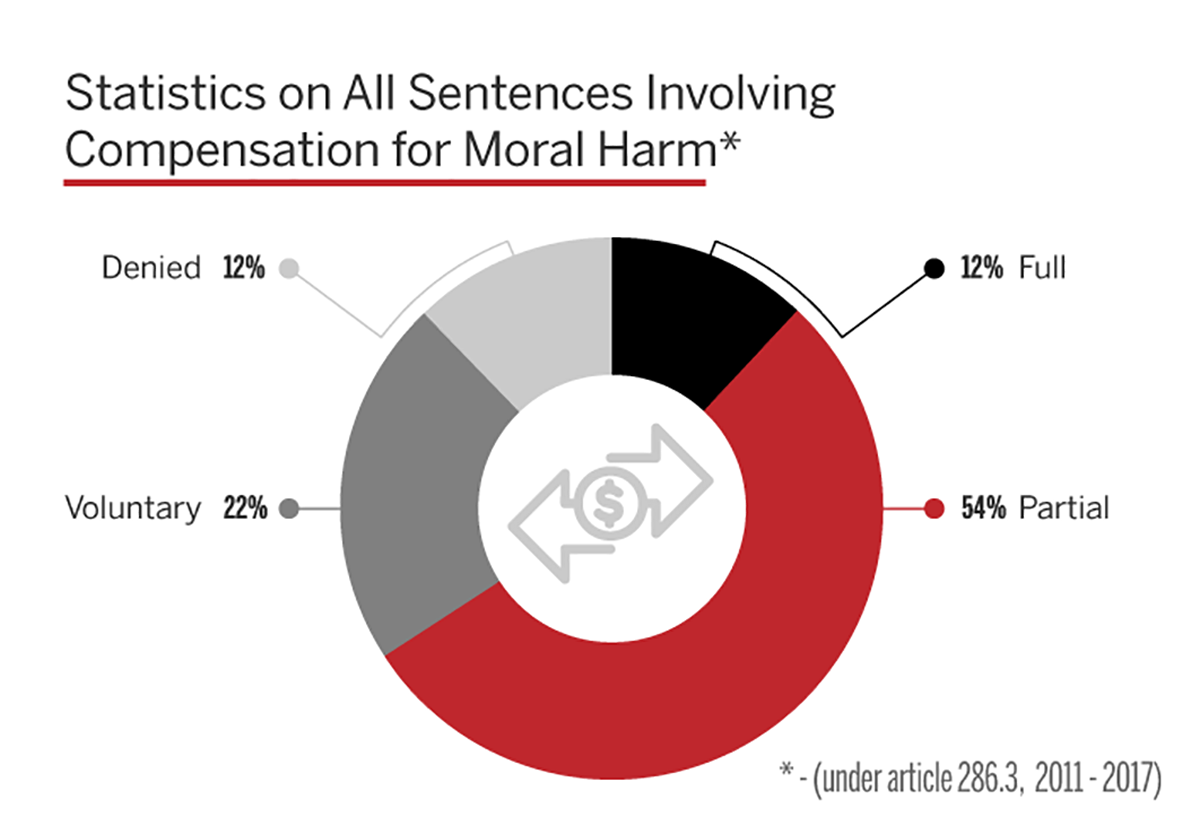

Victims of violent abuse at the hands of officials have the right to file civil claims, and may be compensated for pain and suffering. The amount awarded — or not — depends entirely on the judge.

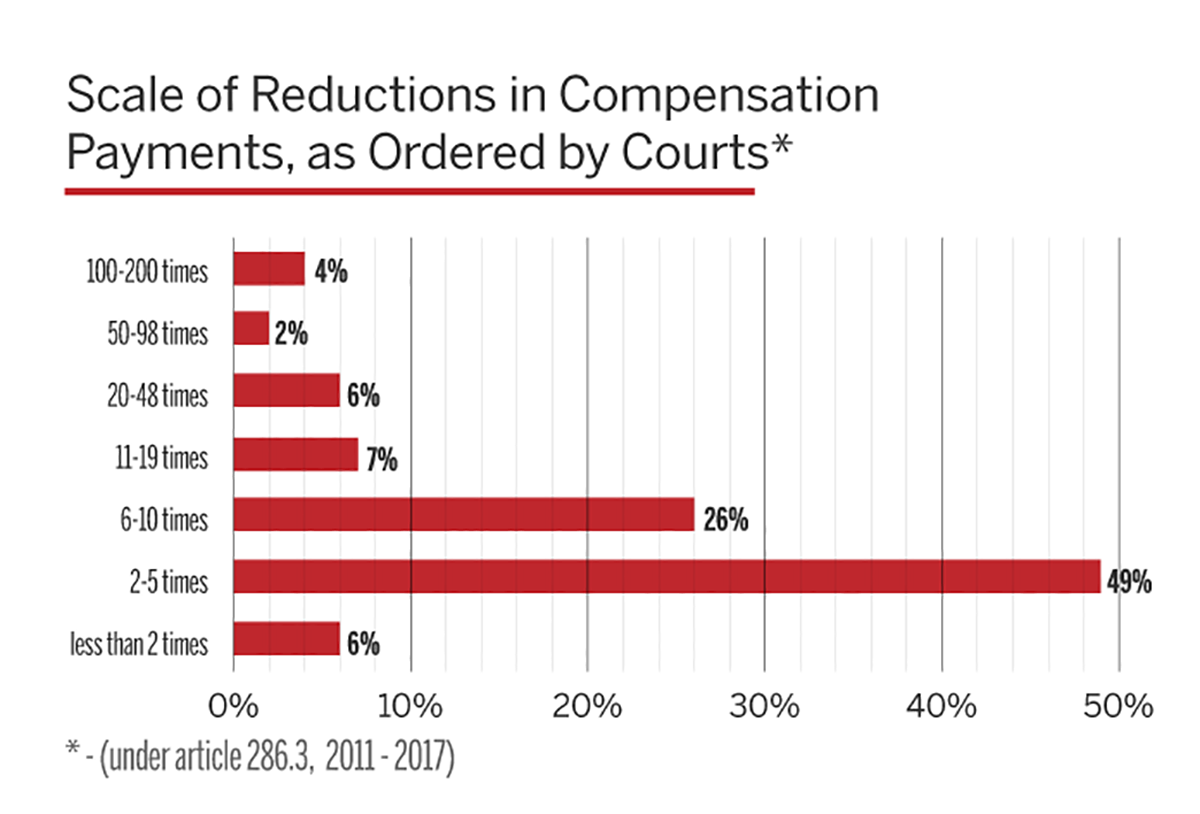

According to this analysis, the amount of money plaintiffs requested was reduced in 82 percent of cases. Half the time, the amount was cut to between 20 percent and 50 percent of what was sought.

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

When the judge decides to reduce the amount of compensation, he or she can either decline to explain his action (“the amount was clearly too high”) or can use general formulations such as “the principles of reasonableness, justice, and proportionality.”

Cases found included such phrasing as: “Considering the degree of physical and moral suffering experienced by the victim, the court considers the claim overstated; it is possible to satisfy them in part” and “the compensation is disproportionate to the [crime].”

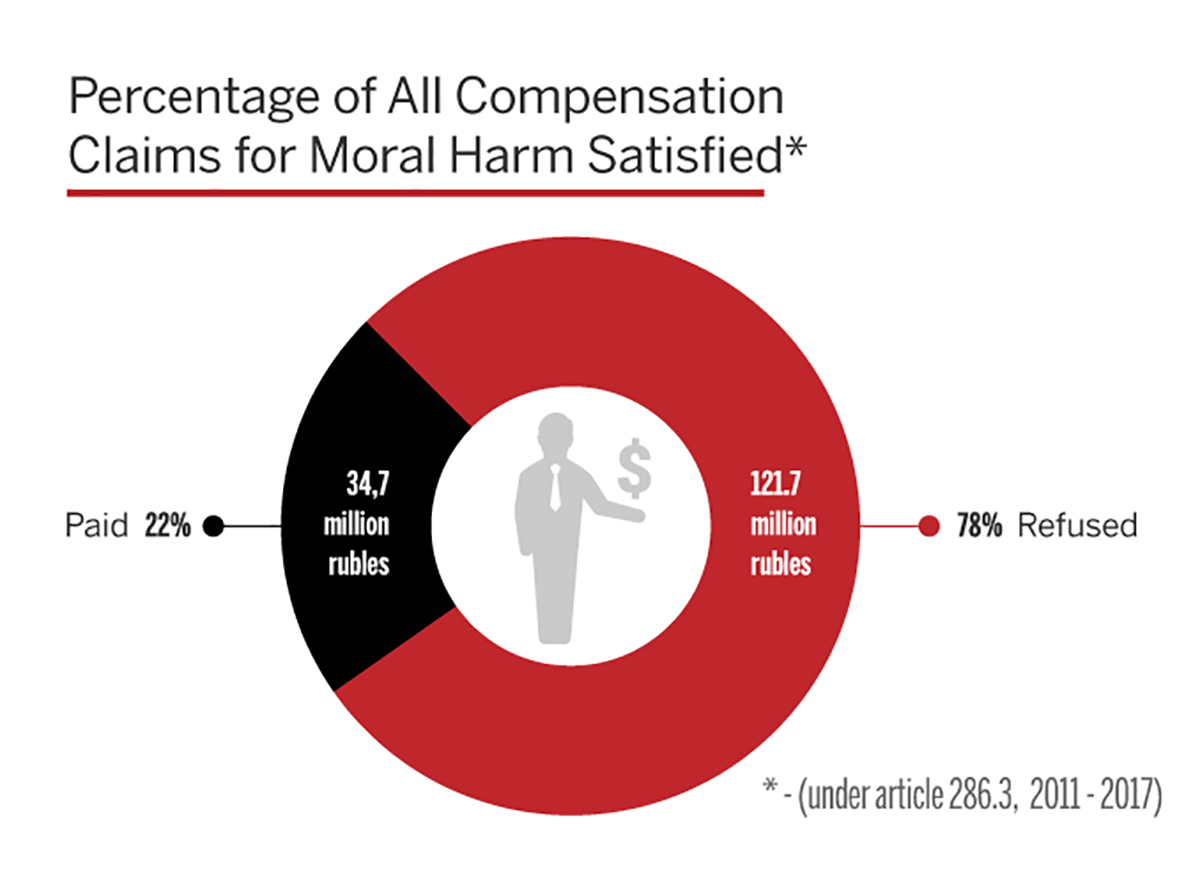

For cases in which the sums awarded were disclosed, 34.7 million rubles (US$ 948,723) were awarded out of 156.4 million ($4,334,486) requested. The largest award was 1.5 million rubles ($43,478), the lowest was 1,000 ($15.40). Half of all awards were between 1,000 and 25,000 rubles ($15.40 to $385).

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

By contrast, according to information provided by the Committee Against Torture, the average amount of compensation awarded by the European Court of Human Rights is between €40,000 and €45,000 ($45,897 to $51,634). The minimum award, in the judgment of the Maslova and Nalbandov case in 2008, was €10,000 ($11,595).

In Russia, compensation is significantly reduced even in payments to relatives of the deceased.

One example involved a military hazing case of a soldier who later committed suicide. The military court of the Voronezh garrison reduced a judgement because the guilty officer had two dependent minor children and a pregnant wife. Instead of a judgment of 2 million rubles ($31 104), the mother of dead soldier received 700,000 rubles ($10 887).

Even when compensation is awarded, there’s a high probability that the convicted person won’t pay, either because they don’t have the means, or simply don’t wish to, according to the Committee Against Torture.