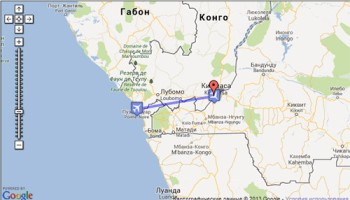

On November 30, 2012, his Ilyushin Il-76 plane crashed in a residential area about 500 meters from the Maya-Maya Airport in Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of the Congo. The 36-year-old plane, manufactured at a Soviet-era Ilyushin factory in Uzbekistan and registered as EK-76300, was on a short 400-kilometer cargo flight from the Atlantic Coast city of Pointe-Noire to the capital.

Five Armenian crew members -- including Gevorgyan -- died in the accident, according to the Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Besides Gevorgyan, Captain Varazdat Balasanyan, former head of the Stepanakert airport, Ara Tovmasyan, Tadevos Hovhannisyan, and Edgar Avetyan all lost their lives. According to the Congolese Red Cross, 32 people included two Congolese police officers were killed and 20 were injured on the ground in the neighborhood where the plane struck.

The disastrous crash raises questions about the safety of aging Armenian planes, how they are regulated and improprieties in their registration that often cause family members grief long after the funerals. Since 2004, planes owned or registered to Armenian outfits -- and often flown by Armenian crews looking for work outside their native country -- have been involved in a number of dangerous and deadly incidents. Authorities in the countries involved, the airlines and even the manufacturer do not appear interested in looking too closely at the cause of the crashes. The real loss is by the families who lose loved ones and then are never compensated even for their loss, in part because of the irregularities in the registrations.

Narineh Hayrapetyan is one of those family members. “The last time we spoke was three hours before the flight,” the engineer’s widow said tearfully. “We spoke for some time and his attitude was normal. He was asking how everyone was. He was always like that; concerned about how friends and relatives were.” Hayrapetyan missed the original TV reports of the crash. Janik, Andranik’s older brother, told the family what had happened the next day. The widow said she held out hope about her husband. But that hope died out quickly.

Finding a Cause

The plane created a huge crater when it crashed short of the runway.

The plane crashed in bad weather -- wind and heavy rain. Nelli Cherchinyan, Press Secretary of the General Department of Civil Aviation of Armenia, reported that according to preliminary information, lightning struck the plane's wing, causing the crash.

Airplane accidents are almost always caused by a number of factors including age, condition, weather, servicing and other issues that align in a deadly pattern. Typically, airplane crashes are investigated by the airline manufacturer, local authorities and sometimes the country of ownership of the plane. But neither Armenia nor the Congo wished to be considered the country of ownership.

Svetlana Suleymanova, head of the Public Affairs Department of the Ilyushin Aviation Complex, told OCCRP that her company had not serviced the plane before it crashed although it is possible other certified companies repaired the plane and renewed flight certificates.

Suleymanova said Ilyushin crash specialists did not go to the Congo. “Generally, our experts participate in investigations,” she said. “But as I understand, the company received no such request in this case.”

After the accident, Congolese President Denis Sassou Nguesso raised speculation by saying that local authorities said the plane should not have taken off in such bad weather conditions. He attributed the blame to pilot error.

Armenian pilots and friends defended the crew. If the weather was so bad, they asked why the flight was cleared to take off from Pointe Noire, and why didn’t the Brazzaville airport divert the flight to a safer airport.

Armen Mnatsakanyan, another pilot who worked in Africa and knew the Armenian crew said, “I state this with 99 percent confidence that [the] crew was comprised of very experienced and very tough guys. There are crews with a weak link. This crew didn’t have one.”

Aero-Service , the company listed as the Congolese flight operator, has a poor history of aircraft accidents including eight serious crashes since 1979 in which mechanical, maintence and operational deficiencies may have been contributing factors.

But former EK-76300 flight engineer Armen Sayadyan, who left the crew in April of 2012, said: “I spoke to Andranik 20 days before the incident. He said the plane was in great shape. Flight frequency had already dropped to one, or at the most, two per week.”

Sayadyan and Ando would never get in a defective plane,” the veteran pilot Mnatsakanyan says. “We would cancel the flight or fix the problem ourselves. But we would never take off knowing the plane had some defect.”

However, older planes are required to go through detailed inspections to look for mechanical and structural fatigue problems not visible to the crew. But the tangled paperwork make it unclear whether that was ever done or even who the real owner of the plane is.

According to veteran pilot Ashot Manucharyan, the plane most likely hit a downdraft, a danger well known to pilots. He theorizes that two factors proved fatal – low altitude and lightning. Noting that lightning hit the wing just 60 meters from the ground, Sayadyan says that even if the engines cut out at 60 meters, it is possible to make a second pass or at least attempt to land a plane before it reaches the runway. But he says a lightning strike would have precluded that.

Who is the plane’s real owner?

Deputy Head of the Armenian General Staff Lieutenant-General Stepan Galstyan.

The real owners of the crashed Ilyshun are as doubtful and contradictory as the circumstances of the crash itself. Paperwork appears to point to an Armenian military official.

According to aerotransport.org, an international trade database, the Il-76 that crashed was manufactured in 1977 at a Tashkent factory in Uzbekistan. It was originally designed as the Il-76K military plane. The Soviet air force used the plane for two decades, and before it was sold, it was modified as an Il-76T civilian aircraft.

Its second owner was the Russian airline Iron Dragonfly. Eventually, the plane joined the fleet of Hungarian-Ukrainian Airlines before being sold to the Moldovan carrier Jet Line International. The Congolese company Heavylift Congo became its fifth owner, which then sold it to an Armenian company.

Tigran Balayan, spokesman for the Armenia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stated that, at the time of the crash, the plane belonged to the Armenian company Ridge Airways. According to Balayan, this information came from the Russian Embassy in the Congo after the Armenian Embassy in Egypt requested it.

But according to aerotransport.org, Aero-Service leased the aircraft from the Armenian company Air Highnesses Ltd., and the listed owner is Ridge Airways.

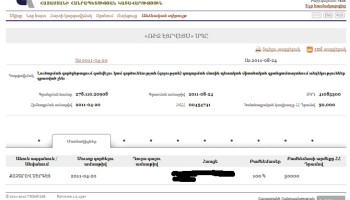

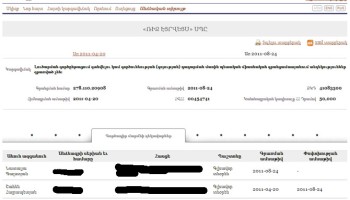

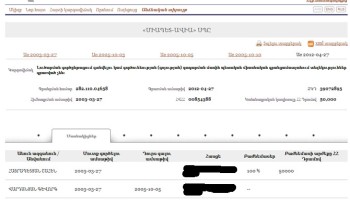

According to the Armenian State Registry of companies, Ridge Airways is owned by Sergey Kocharov who founded it on April 20, 2011.

But in a letter to the Armenian news site Hetq.am, Captain Valery Poghosyan, who also works in Africa and said he was friends with the crash victims, wrote that the plane belonged to the Deputy Head of the Armenian General Staff, Lieutenant-General Stepan Galstyan.

The registry documents list Natalia Galstyan as general manager. She is the wife of General Galstyan. Poghosyan claimed that four other planes (two An-12s and two Il-76s) owned byGalstyan also operate in Africa. Poghosyan estimates that the planes were worth about US$9 million. Hetq.am tried to speak with Galstyan, but Galstyan refused multiple interview requests.

According to the Armenian Ministry of Defense website, Galstyan has been an officer in the Soviet and Armenian air forces since 1983 and is deputy head of the Armenian General Staff.

Ministry of Defense spokesman Artsrun Hovhannisyan refuted the ownership, claiming it is an attempt to smear the good name of the military. Hovhannisyan told ilur.am that Ridge Airways no longer exists, and that the plane never belonged to that company. He claimed that Galstyan was only indirectly affiliated with the company for a time.

The company's operator's certificate -- issued by the General Department of Civil Aviation of Armenia -- expired on Sept. 8, 2012, and it is not authorized to operate any aircraft until a new certificate is issued, according to Nelli Cherchinyan, Press Secretary of the Civil Aviation Department.

From its founding until August 24, 2011, Shahen Hayrapetyan (no relation to the flight engineer killed in the crash) was the general manager of Ridge Airways before being replaced by General Galstyan's wife. The Defense Ministry spokesman says that the Il-76 had no connection with Ridge Airways. The plane was listed as operated by Air Highnesses Ltd. That company’s founder and director is also Shahen Hayrapetyan.

However, according to aerotransport.org, Ridge Airways registered the plane in Armenia in the spring of 2009, two years before Ridge Airways Ltd formed in April 2011. Air Highnesses was established in February 2008.

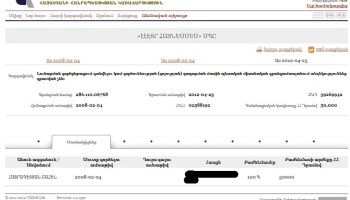

Shahen Hayrapetyan was also the founder and director of Miapet-Avia Ltd., which lists the same contact information as Air Highnesses. Miapet-Avia is listed as the owner of two aircraft that crashed: EK-12305 in Afghanistan on June 29, 2006, and EK-11660 in the Congo on January 25, 2008. Shahen Hayrapetyan died in early April, 2013.

In response to a Hetq.am query, the General Department of Civil Aviation of Armenia stated that the plane that crashed on November 30 had no Armenian registration. But the EK-76300 registration number remained on the body of the plane (EK is the national registration symbol for Armenia aircraft and the digits are the specific registration number). They should have been changed on the plane body if the aircraft had its registration legally changed.

Serob Karapetyan, who heads the Civil Aviation Department’s Flight Readiness Unit, said the plane had been removed from the Armenian airplane state registry a long time before the accident. He could not produce any documents showing this, nor would he say in what country the plane was registered after being removed from the Armenian registry. In a letter to Hetq.am he wrote: “The Il-76 airplane that had an accident in the Congo on Nov. 30, 2012, didn’t have Armenian registration on that day. Thus, in regards to the accident, the General Department of Civil Aviation attached to the (Armenian) government has no information in its possession.”

In the files of aerotransport.org, the last operator of this plane is shown as the Congolese company Aero-Service. It is noted that a lease arrangement that began in August of 2011 indicated that the owner was still regarded as Ridge Airways. Veteran pilot Poghosyan said that the EK-76300 had been in the Congo for 16 months.

Shahen Petrosyan, who headed Armenia’s Civil Aviation Department from 1993-1996, says that the existence of the EK-76300 number on the plane that crashed and the fact that it was removed from the Armenian airplane registry clearly contradict one another. According to Petrosyan , the existence of an Armenian number on a plane would be correct only if the rental lease was short-term and there was no change in the plane’s registration.

Airplane’s Doctored Documents?

Flight engineer Andranik Gevorgyan, who died in the crash.

Former Il-76 flight engineer Sayadyan says the plane flew within the Republic of Congo, but also in the neighboring countries of Gabon and Equatorial Guinea.

Each plane has a legal flight lifespan, which limits how many flight hours a plane can fly. The original flight limit for the Ilyushin model was 15,000 flight hours or 6,000 flights. As of 1994, the flight life for certain plane models was lengthened to 20,000 flight hours or 7,000 flights. After reaching these limits, a plane can only be operated if it has been completely overhauled and granted a new flight lifespan.

There is no record of any investigation that sought to determine how many hours the plane flew before the crash. It had been flying for 34 years, a very long time for the model. Most Il-76 planes use up their 20,000 flight hours in 20 years.

Poghosyan, a veteran pilot, said the process to requalify a plan that has reached the end of its lifespan is complex. It requires a detailed check and report on the plane by an authorized repair facility. Such a facility does not exist in the Congo region. Poghosyan said, however, that the planes documents might have been forged which may have allowed the plane to be illegally registered.

“When the Soviet Union collapsed, everything collapsed. During the Soviet era, whatever the instructions from above, the servicing engineer would never in his life sign off on a plane’s paperwork, because there were a hundred types of supervision. The guy knew that if he were caught, he’d be sent to jail. But from the 1990s until today, the accepted practice is that if you can circumvent a law, they’ll do it,” said a fellow pilot who asked not to be identified for fear of losing his job for sharing information about a common practice. “I have many friends who have flown in Africa and they all say the same thing – that broken down equipment is purchased, that the mechanical servicing is also wanting and sometimes stuff doesn’t work at all.”

Sayadyan and Mnatsakanyan, who have both worked in the Congo, disagree with Poghosyan and argue that monitoring by the Congolese Aviation Agency is strict. According to Sayadyan, an inspection team arrives at least once a month to check all the paperwork. Mnatsakanyan says the Congolese inspectors are graduates of the aviation institute in Kiev.

“When a new plane arrives, it doesn’t fly until it’s checked from head-to-toe. It takes several days before permission to operate is granted,” says Mnatsakanyan.

Karepetyan from Armenia’s General Department of Civil Aviation refused to comment on Poghosyan’s allegations, saying that if Poghosyan would make his claims in person, the aviation agency would be ready to present counter-arguments. Poghosyan has not been available for further comment.

Meanwhile Armenian pilots continue to fly earning between $1200 and $3000 per month in a lucrative business for Armenia but one that takes them away from family for long periods. Still, for some it is the only option. As Mnatsakanyan says: “Maybe Andranik could have worked as a flight engineer on the only two Il-76 planes left in Armenia. Where else was Ando to work?”