Every night this week, the streets of Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital, have been patrolled by druzhinniki — a term that once denoted semi-official Soviet militias.

Today, the word refers to volunteers who have banded together to keep the peace in the wake of a protracted uprising.

Warming themselves with donated food and hot tea, coordinating their movements on Telegram channels and Instagram accounts, and soliciting donations online from across the world, volunteers patrolled residential neighborhoods, protected shopping centers, and defended government buildings against intrusions.

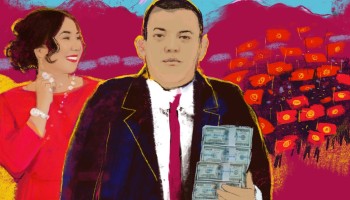

The trouble started after a parliamentary election marred by vote-buying prompted protesters to pour onto the streets on October 5. One person was killed and dozens injured in confrontations with police. Within hours, the parliament building was in the hands of the crowd; by morning the government appeared to have fallen.

For the following week, its replacement was a bewildering collection of shifting power centers. Competing demonstrations turned violent. It wasn’t until the next weekend that a controversial adviser to deposed president Kurmanbek Bakiyev was approved interim prime minister in a move that seems likely to engender further conflict. And even as a curfew and state of emergency was declared on October 9, uniformed police had nearly disappeared from the streets of the capital.

Seeing no other option, Kyrgyz citizens took their fate into their own hands.

In their spontaneous self-organization at a time of state paralysis, their actions were reminiscent of another period, earlier this summer, when Kyrgyzstan was struck by the twin catastrophes of quarantine and pandemic. A woefully inadequate government response left people hungry and sick, unable to afford medicine or find doctors. During the worst days in the summer, a shortage of both public and private ambulances and hospital beds left many people to die. Even those with the most severe symptoms were unable to get into overcrowded clinics.

Then, too, Kyrgyz citizens found that relying on their government costs lives — and took matters into their own hands. Social media platforms became crucial tools of self-organization. Volunteers bought groceries for those in need and on mopped floors at overwhelmed hospitals. Doctors took to Twitter to educate citizens and consult with patients. And all across Kyrgyz social media, activists raced to provide hospitals with protective equipment, medicine, and food.

As fears of another coronavirus wave rise with the approach of winter, Kyrgyz citizens may again be left to fend for themselves. But even if the future of their government looks unclear, at least, as they kept telling reporters, they have each other.

“When [the uprising] happened, I understood: Who, if not me?” said Kuba Mirzabekov, a 21-year-old volunteer who spent at least two nights patrolling the streets of Bishkek. “We are a little country, and every person can do something big.”

“Our Only Goal is Safety”

Despite Monday’s uprising, many aspects of life in Bishkek looked almost normal last week. Busses kept running, shops and restaurants stayed open, though with reduced hours, and people kept going to work.

But signs of crisis were everywhere. Every day, demonstrations erupted around the city as supporters of former presidents and prime ministers jockeyed for power. On Friday, three separate protests began in different neighborhoods and collided in the center, ending in chaos and gunfire.

Things looked different by night.

Small groups of volunteers were everywhere, identifiable by their reflective vests, colored armbands, or homemade insignia made from red tape. Some protected specific locations, like the General Prosecutor’s Office and the government house. Others patrolled the streets in groups of three to five.

At fixed gathering points, coordinators bent over their cell phones, exchanging information and sending teams to trouble spots. Misinformation was a constant preoccupation, and spotters in cars were sent to see if new pieces of intelligence checked out.

They were all looking for looters, vandals, or other troublemakers — the word “marauders,” often said to be from out of town, was the almost universal description. Many recalled the experience of previous revolutions, when government buildings were set ablaze and shopping centers were looted.

Nobody got enough sleep.

“I can’t even give a normal interview,” apologized Sofia-Aidana Murzaeva, a board member of an organization called Center of Enterprising Youth. “For days we’ve been trying to defend our beloved Bishkek from marauders,” she said. “We’re defending private homes and shopping centers. We’re against disorder.”

But the mood wasn’t tense, and the volunteers, many of them very young, went out of their way to show kindness to strangers. Reporters were repeatedly offered tea, hot food, or rides home.

Jokes, laughter, and friendly conversation were ever-present — except when volunteers’ phones lit up with messages. Then, everyone went quiet to digest the latest developments.

When cell phone coverage disappeared, people opened their wifi networks to help strangers get in touch with their families. Napishi rodnim — ”write your loved ones” — was the name of one network in the center of town.

Help came in other forms as well. On cold nights, teams of volunteers drove around the city bringing hot tea to the brigades at their gathering points. Near the general prosecutors’ office, cars stopped every few minutes and asked if anyone was hungry. Some people carried a veritable canteen in their trunks, giving away fruit, pies, salad, and bread. Other cars honked in support as they drove by.

The volunteers came from all walks of life. Reporters met Kanatbek Zhumushbekov, who said he used to work in law enforcement, at a gathering point outfitted with tents, heaters, and hot food. He explained how he and his friends got a group together to patrol neighborhoods in southern Bishkek. “I recorded a video and said, please come,” he said. “Someone created a logo. Literally in half a day, we organized this.”

At the side of a busy road in a residential area, two women served meat-filled pies, bread, and fried dough to patrolling volunteers. They said they had collected hundreds of dollars after asking for donations on Telegram.

“From Moscow, our people sent money. From here in Kyrgyzstan,” said Nurzada Berdibayeva. “Honestly, we’re in shock that in one day you can collect so much.”

“Everyone started donating,” chimed in her friend Meerimai Saagyndykova. “So for the third night, we’re buying [food] and driving around. It’s an indescribable feeling. It’s so great that so many people want to help.”

Time and again, volunteers took pains to draw a line between what they were doing and the broader political situation. In a country where politics is associated with narrow personal or clan interests, corruption, and incompetence, the very concept has become toxic.

“Our only goal is safety,” said Azamat Saparali uulu, a young web developer. “There is no other goal. We want to supplant the work of the police. Some politicians came to us and tried to tell us about themselves. But we’re not into that. We’re completely apolitical.”

Nurilya Cholponbai is an experienced organizer whose organization, Generation BEST, was active during the worst of the coronavirus pandemic and now provides meals and hot drinks for patrolling brigades.

“The people trust us more, because we reacted faster,” she said. “Volunteers are much more agile. We just buy the stuff and go. People see us, and we can offer help faster than the government.”

“In other countries it’s better organized, the government helps,” she said. “But we had nothing like that, so we had to do it ourselves. Wherever you go, when you say you’re a volunteer — like when you get into a taxi, the driver will drive you for free. That’s how much respect people have for us. So when we hear a cry for help, we have to go. We can’t let them down.”

Kuba Mirzabekov, the young volunteer who had remarked that individuals can make a difference in a small country like Kyrgyzstan, expressed some hesitation about keeping a distance from politics.

“Right now they’re saying the druzhinniki are apolitical,” he said. “But every person has a political position. So I’m questioning that a little. … I have to think about it.”

Still, he said, the best policy for now was neutrality. “This could divide the volunteers. I think the best position right now is to be outside politics. If you want to express your political opinion, you should take off your vest.”

Most of all, volunteers stressed how inspiring they found their common work. They hailed the rise of a new generation after decades of disappointment in Kyrgyz government.

“We have really great youth that we can be proud of. I think we’re on our way to a good, conscious civil society,” said Zhumushbekov, the former police officer. “Our neighbors are jealous of us. Not just in the [former Soviet Union], but other countries see our organization. You saw this during the pandemic. Our volunteers carried much of the burden on their shoulders.”

Another volunteer credited the pandemic with forging a new generation.

“We went through the quarantine together. This united people, because they went through such grief and such losses,” said Ruslan, who reporters met guarding the government house. “In 2010, many people didn’t understand what they were doing. This year, people have a wider perspective.”