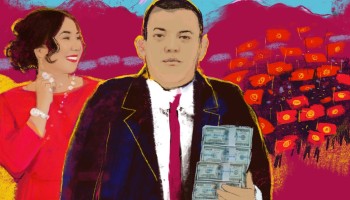

For years, the deputy head of Kyrgyzstan’s customs service enabled customs fraud from the shadows.

In 2017, he was unceremoniously fired. But Raimbek Matraimov appears to have found a way to stay in the customs game with the help of some old friends, a family of Uighur smugglers called the Abdukadyrs.

Between them, the Matraimov and Abdukadyr families have established control of three major Kyrgyz customs terminals through trusted confidants.

Some of these men were relatives of the Matraimov family. Others appear to be proxies with no business experience and backgrounds in fields like professional MMA fighting or law enforcement. When contacted by reporters, a wrestler who owned a company that operates one of the facilities seemed confused. “I don’t work,” he said. “I’m just a loafer.”

Now, the three terminals have become the only option for trucks that bring goods from China into Kyrgyzstan.

Industry professionals say that bribery and other illicit practices take place in these terminals on a daily basis, and many accuse Matraimov relatives working in the customs service of enabling large-scale corruption.

Aside from providing lucrative streams of legal and illegal income, the terminals also benefit Abu Sahiy, a major Central Asian trading business run by the Abdukadyr family that previous investigations have implicated in wide-ranging customs fraud. One of the southern terminals is reserved for Abu Sahiy’s nearly exclusive use.

In his only known public comment about his relationship with the Abdukadyrs, Raimbek Matraimov told the outlet Asia News that he knows the head of the family, Khabibula Abdukadyr, as an “investor on an international scale” with whom he had to work due to his position in the customs service.”

Matraimov could not be reached for comment for this story. An assistant of Iskender Matraimov, Raimbek’s brother and a member of parliament, wrote that the family would be unable to provide any comments until after this Sunday’s parliamentary election. The Abdukadyr family and the customs service did not respond to requests for comment.

The Northern Route

Kyrgyzstan’s underdeveloped railway network means that most of the trade goods that enter the country from China must travel by truck. Rugged geography forces these trucks to pass through just two main routes that wind through the mountains.

Along both of them, either the Matraimovs or the Abdukadyrs will be waiting.

What locals call the “northern route” runs from the city of Kashgar in northwestern China, crosses into Kyrgyzstan through the Torugart pass in the Tian Shan mountains, and leads past the capital of Bishkek. From there, it continues onward to oil-rich Kazakhstan and Russia — major markets for Chinese goods.

For years, trucks plying this route usually went through customs procedures at a crowded facility in Dordoi, a sprawling and chaotic Bishkek market.

One entrepreneur saw an opportunity to fill a need by creating a modern, all-in-one logistics center nearby. The new UniLab terminal in the town of Kant, 25 kilometers from Bishkek and just 20 minutes from the Kazakh border, was to provide modern “single window” service: It would have a customs clearance facility, temporary warehouses, payment operations, and even a sports ground and hotel for weary drivers.

The initiator of this ambitious project, Syrgak Kenzhebaev, worked furiously to find the money to make it a reality. He established a partnership with a well-connected Russian insurance broker who reportedly had close ties to the head of the country’s customs service. He even got a friend to join the company.

Initially, things looked promising. Construction on UniLab’s 37-hectare territory got underway, and the company received licenses to function as a temporary storage warehouse and a customs service provider.

By the spring of 2016 the facility was finally ready for business, even hosting an opening ceremony with government officials in attendance. But the trucks never came.

“[UniLab] had received all the permissions, but for some reason no cargo was arriving,” said a professional in the industry with knowledge of the situation.

The person blamed customs, explaining that officers kept redirecting incoming trucks elsewhere.

UniLab sat idle, and Kenzhebaev was falling into debt and getting desperate. In the words of another insider, UniLab never got off the ground because senior customs officials, including Matraimov, made sure it could not succeed.

“As far as I know, [Kenzhebayev] tried to negotiate with them in good faith, saying, ‘Take this many percent, take this much.’ But it was no use,” another source said.

Even Kenzhebayev’s Russian ties proved useless.

He hosted members of parliament and the first vice prime minister at UniLab to seek support. He even wrote to President Almazbek Atambayev.

In the end, his efforts were in vain. UniLab did start operating — but only after Kenzhebaev and all his partners were gone. Under increasing pressure, they sold the company in November 2016.

The two men who initially took over — a wrestler and a police officer — held onto it for just seven weeks. One could not be reached by reporters; the other said he had nothing to do with the company.

UniLab then ended up in the hands of two other men, one of whom is an associate of the Abdukadyr family. The other has the appearance of a proxy, with no public presence or known business experience.

The UniLab Front Men

A business partner of Kenzhebaev’s, who cannot be named for safety reasons, described the deal as a corporate raid, using the Russian term “reiderski zakhvat” to refer to the practice, common in many former Soviet countries, of exerting pressure on company owners to sell their businesses for little or nothing, often with support from crooked officials.

“The company was simply grabbed away,” Kenzhebaev’s partner said.

“He defended himself alone. ... There weren’t such people around us that could go against the state machine. It was pointless of him to ask anyone, because nobody would come to his defense.”

When reporters approached Kenzhebaev, he refused to discuss UniLab. On a visit to Kazakhstan in December 2019, he was arrested in the Almaty airport and extradited to Kyrgyzstan. A Chinese citizen had filed a complaint against him for fraud, Kyrgyzstan’s State National Security Committee said.

In a public video statement right after Kenzhebaev’s arrest, his romantic partner, the daughter of prominent Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov, said she believed the charges were an attempt to put pressure on her anti-corruption movement, Umut 2020. She declined to speak to reporters for this story.

Though Kenzhebaev has been in detention for nine months, he has not been indicted.

Meanwhile, drivers and logistics specialists told reporters that UniLab is now, in the words of one broker, where “everything happens.”

While it was in Kenzhebaev’s hands, customs officials steered incoming trucks elsewhere. Under its new ownership, they are directing all Chinese goods along the northern route to the facility.

The Southern Route

Kyrgyzstan’s only other border crossing with China, Irkeshtam, is a hundred miles southwest of Torugart as the bird flies — but far further by road. Trucks originating in Kashgar that cross here will pass through the southern trading city of Osh and on to Uzbekistan’s capital, Tashkent, in what locals call the “southern route.”

The dominant player on this route is Abu Sahiy, the trading empire established by the Abdukadyr family. (The word sahiy means ‘generous’ in Uzbek, while Abu is short for Khabibula, the family’s patriarch.) This business, which actually consists of multiple Chinese, Kyrgyz, and Uzbek companies, hauls goods from China’s Xinjiang region into Kyrgyzstan, then to Tashkent and beyond.

After crossing into Kyrgyzstan from China, Abu Sahiy trucks — and almost exclusively Abu Sahiy trucks — stop at a private customs terminal right on the Uzbek border run by a company called Mega Logistik. This facility, which people in the industry simply refer to as “Abu Sahiy,” is used to unload the Chinese goods. They are then reloaded onto different trucks for onward travel to Uzbekistan.

On paper, Mega Logistik was founded by a man with an address in the Kara-Suu district who was 21 years old at the time. (When reporters tried to reach him, a man who answered the phone said he was someone else and asked them not to call again.) But the land the Mega Logistik terminal occupies is partially owned by two men closely connected to the Matraimov family and their businesses:

The Mega Logistik Proxies

A large parking lot adjacent to the Mega Logistik terminal is used by cargo trucks.

The land on which the parking lot sits, right on the international border, is owned by local Kyrgyz authorities. In 2004, the temporary right to use the land was given to a company called Wholesale International.

Ten years later, two nephews of Raimbek Matraimov acquired partial stakes in the company.

The land had been empty for many years before the parking lot was built in 2018 — the same year Mega Logistik became a full-fledged customs terminal (it had previously been used as a temporary cargo storage facility).

Some of the company’s taxes were paid by the two nephews, Erlan and Nursultan Tursunbaev, and by Nurilya Bechelova, the Matraimovs’ accountant in Osh.

Though the Mega Logistik terminal is a major operation — Kyrgyzstan’s anti-monopoly regulation agency described it in December 2016 as having a “dominant position” on the market — it is reserved almost exclusively for the use of the Abdukadyr family’s cargo empire.

When a reporter called several independent customs brokers to ask about importing cargo from China, one did not even name the facility as a possibility. The only option, he said, was another southern terminal.

“We’re in the south,” he said. “Here there’s only Kara-Suu.”

The Kara-Suu Terminal

This terminal, stationed on the site of a Soviet-era flour factory, was once operated by a company belonging to people close to former President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who was deposed in a revolution in 2010.

It is still operated by the same company, but now it is owned by people close to the Matraimovs.

Business records show that this happened while Raimbek Matraimov was still climbing the career ladder in the customs service — in a manner that suggests, at the very least, a possible conflict of interest. Its complex corporate history, which includes a nearly five-year partnership with the Kyrgyz state and several reorganizations, is a veritable parade of Matraimov relatives and associates:

The Saga of the Kara-Suu Terminal

“Save Us From the Close Associates of Raimbek Matraimov”

Previous investigations by OCCRP and partners showed that extensive corruption took place within Kyrgyzstan’s customs service during Raimbek Matraimov’s tenure as its deputy head. They also showed how Matraimov’s patronage helped the Abdukadyr family’s Abu Sahiy trading empire flourish at the expense of its competitors.

By the end of 2017, Matraimov had been removed from his position as deputy head of customs. The two southern customs terminals were in full operation, and in the north, UniLab was about to get off the ground.

The corruption within those facilities, and in the wider customs service, continued despite his removal. In 2018, a group of international traders wrote a joint letter begging the country’s president, speaker of parliament, and prime minister to address the problem, which they said was making it nearly impossible for them to do business.

“Save us from Raim Matraimov, so-called ‘holder of the red book [financial ledger] of Kyrgyz customs and immovable khan of Kyrgyz customs’ and his close associates, who implement and execute his corrupt schemes to the letter,” reads the conclusion of the 11-page document.

The bulk of the text alleged, in detail, how people loyal to Matraimov engaged in corruption at the terminals, lamenting that these officials — the letter listed about a dozen names — had been reinstated to senior positions after being initially dismissed in the wake of his ouster.

The letter alleged they were forcing cargo operators unaffiliated with the Matraimovs, or with the Abdukadyrs’ Abu Sahiy company, to pay large bribes under various pretexts, with some drivers having to pay up to $4,000 per truck before being allowed to cross the Kyrgyz-Uzbek border.

Such practices, the letter alleged, have made Matraimov relatives vast amounts of dirty money:

The Matraimov Relatives

The businessmen’s letter, as well as independent interviews and other sources, allege that relatives of Raimbek Matraimov led and participated in customs corruption.

“We, businessmen, work day in and day out to make enough for apartments in high-rise buildings. Meanwhile, young guys (around 30-35 years old), perpetrators of Raim Matraimov’s corruption scheme, live in three-story houses and drive expensive Lexus SUVs,” the letter reads. “These people came to work [in customs] only 3-4 years ago, and we know from which financial sources they receive so much money.”

Sources in the cargo industry described a host of advantages enjoyed by insider companies with connections to Raimbek Matraimov. Among other schemes, customs officials allow them to falsely declare expensive goods as cheaper ones, making their trade along these routes much more profitable. And while goods driven to Tajikistan by independent operators “are thoroughly inspected and unloaded from trucks,” ending up “sitting at customs posts for weeks and even months” if bribes are not paid, “the goods of Raim[bek] Matraimov’s associates pass without being unloaded, and the customs seals on their trucks aren’t even broken.”

As a result of these advantages, the businessmen wrote, importing goods to Kyrgyzstan is faster and cheaper for companies associated with Matraimov.

On multiple occasions, the letter mentions cargo carriers associated with the Matraimov family, such as “freight companies of Ruslan[bek] Matraimov, the younger brother of Raim[bek] Matraimov; and the okul bala of Raim[bek] Matraimov, the man named Almaz [Almazbek Arstanbaev], who is in charge of the Kara-Suu customs terminal.”

Reporters found several cargo companies owned by and associated with the Matraimov family, including Delux Trans, formerly owned by Ruslanbek Matraimov, and the Baiboto group of companies, owned by Almazbek Arstanbaev.

But the only insider company mentioned in the letter by name is the Abdukadyr family’s Abu Sahiy, which specializes in transit cargo. Chinese goods carried through Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan are “allowed to be transported only ... through the Abu-Sahiy company affiliated with [Matraimov],” the letter reads. “In other words, other businessmen are not able to transport cargo to Uzbekistan.”

The description appears to be no exaggeration. This June, Kyrgyz truck drivers erupted in protest that Abu Sahiy was the only company whose trucks were being let through the southern Irkeshtam crossing.

Some Official Data

Speaking on behalf of the drivers, entrepreneur and former driver Isabay Sulaimanov told OCCRP that “Ninety percent of the cargo [from China to Kyrgyzstan’s Uzbek border] is driven by Tarim Trans,” referring to the company representing the Kyrgyz portion of the overall Abu Sahiy business.

“Wherever we go, it’s Abu Sahiy’s interests that are being protected everywhere,” a driver said. “Our passage across the border is 100 percent hindered by Abu Sahiy.”

“They’ve taken away the bread of so many people,” another driver said.