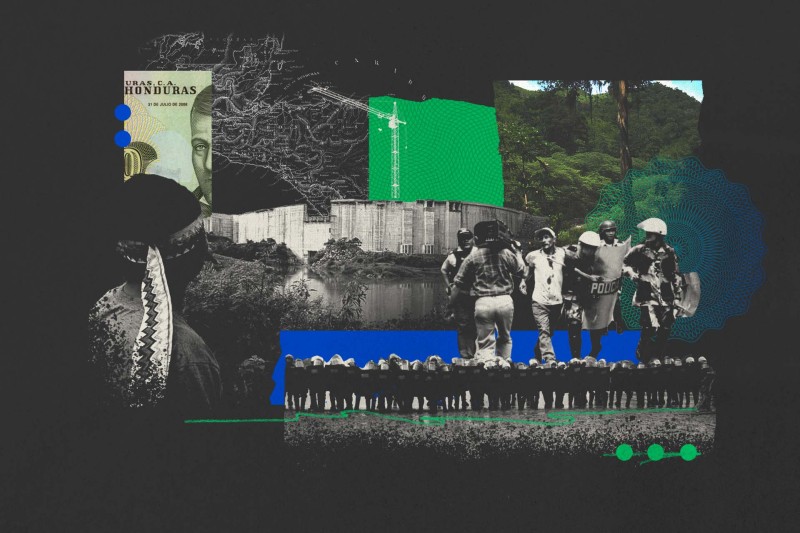

At least nine activists who opposed dams backed by the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) development bank have been murdered, according to court cases, media reports, and statements by human rights groups.

CABEI — which calls itself the “Green Bank of Central America” — has lent millions of dollars to sustainable energy projects.

They include 25 hydroelectric plants the bank has backed over the past 30 or so years. According to outgoing president Dante Mossi, the bank is now eyeing two other controversial dams.

But some of those projects have cost more than money.

At least nine activists who opposed these dams have been murdered, according to court cases, media reports, and statements by human rights groups. Some were shot at while traveling to protests; others were reportedly targeted for speaking out.

In all of these projects, CABEI gave or pledged funds after people were killed. In two additional cases, the bank continued to back the dams even after protests from indigenous communities, and public reports of violence against them.

OCCRP and Columbia Journalism Investigations found CABEI ignored red flags when agreeing to fund the controversial Agua Zarca dam in Honduras. Reporters examined two other hydroelectric projects the bank financed and found similar failings.

The Battle For Babilonia

Carlos Roberto Flores was relaxing with his family in the backyard of his home, in the village of La Venta, in Gualaco in northeastern Honduras, when six men burst in and gunned him down in a hail of bullets.

According to witness accounts cited by rights groups, media reports, and a visiting U.S. academic who was in the hamlet at the time, Flores was murdered by guards from Energisa S.A. de C.V., a Honduran company that was building a small hydroelectric dam in the area.

Rights groups said Flores, who was 28 when he was killed in June 2001, had become a target as a leader of protests against the dam. A couple of months earlier, a human rights organization had published a list of people it said were being persecuted by Energisa in a local paper — and Flores’ name was at the top, according to Daniel Graham, an academic who was studying the Babilonia dam.

“Carlos Flores was selected as an assassination target for being one of the biggest opponents of the installation of the Energisa project,” Graham wrote in an account published by several human rights groups.

Neither Energisa nor Honduran police responded to requests for comment.

Babilonia was one of a spate of small, privately owned hydroelectric dams built in Honduras around the turn of the 21st century. In 1998, the government passed a new law to encourage private investment in hydroelectric projects, which were lauded as environmentally friendly sources of energy, promising them "preferential treatment."

CABEI had supported the initiative, promising funding for several of the new dams. These included Babilonia — a dam of around four megawatts named after the river on which it was built — which Energisa promised would provide electricity for nearby homes and draw in investment.

But community members warned the dam would destroy the region’s many waterfalls and rivers, and put local coffee farmers out of business. Many feared it would also impact the nearby Sierra de Agalta National Park, a haven for wildlife that forms part of an important migration corridor for tapirs, pumas, and jaguars, among many other animals.

Their protests were met with violence and intimidation. Rafael Ulloa, who was the mayor of Gualaco at the time and led the protests against Babilonia, said he received anonymous death threats and was physically attacked on several occasions. Another protest leader, Jose Zuniga, told human rights officers that several of his farm animals were hacked to death with machetes.

Jose’s brother, Isidro Zuniga, said people were too scared to leave their homes at night for fear of being arrested or stopped by Energisa’s security guards.

“The community lived in a state of panic,” he told reporters.

The month after Flores was murdered, the protesters took their fight to the capital. More than 300 people converged on the National Congress to demonstrate, before visiting CABEI’s headquarters and the embassies of several of its member states.

“We visited many CABEI member embassies so that they could understand the kind of project they were financing,” said Isidro Zuniga.

Police confronted the demonstrators using tear gas, clubs, and rubber bullets, leaving more than a dozen people injured. International rights groups condemned the violence and the arrests of 20 protesters.

Despite the protests, CABEI agreed to loan Energisa $2.7 million, a little over half of the $5 million needed to build Babilonia. The bank did not reply to requests for comment about its decision-making process.

Mark Bonta, a U.S. geographer who assessed the environmental impact of Babilonia for the protest groups, said CABEI and the government should not have supported the dam after Flores’ death offered “clearcut, photo-documented proof that Energisa was acting with impunity.”

“Even after the murder of Flores they wavered little, and when the storm of controversy and street protest turned into slow-moving official investigations, they renewed their support,” he wrote in an academic paper about the case.

“Even after the murder of Flores they wavered little, and when the storm of controversy and street protest turned into slow-moving official investigations, they renewed their support”

Mark Bonta, Geographer

CABEI did not respond to requests for comment.

Irreversible Damage

CABEI backed Babilonia not only after widespread violence against protesters, but also despite a raft of environmental concerns dam opponents had raised, and allegations of irregularities in the project’s approval process.

The month after Flores was killed, the National Coordinator Against Impunity (CONACIM), an umbrella group of Honduran human rights organizations, produced a report detailing irregularities during the approval process for Babilonia. It then submitted a petition to CABEI, calling for the bank to stop financing the dam.

The petition said that Honduras’ Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources had signed contracts with Energisa before the project was granted an environmental license, “in open contradiction and violation” of the law. The deal was approved by presidential decree in March 2000, before a legally required environmental impact assessment had been carried out.

Even when the environmental impact assessment was carried out, it had multiple problems, according to CONACIM. Importantly, it failed to address environmental and forestry laws, overlooked critical information about who owned land that would be impacted, and ignored the concerns of local people.

CONACIM also pointed out gaps in the technical analyses that formed the basis of the study, criticizing Energisa for providing “totally or partially false data.”

"[We] do not oppose CABEI or any other entity channeling international funds for national projects that will mean economic and social development," they wrote.

“On the other hand, we are opposed to the fact that the use of external funds for projects of dubious reputation are naively based on documents coming from corrupt authorities at the highest level.”

Bonta, who the protesters asked to review Energia’s environmental impact assessment, agreed it was “woefully lacking” in data on how the dam would impact the region’s geology and wildlife. Maps included in the report had also been “to a large extent fabricated to make it look as if people would not lose their coffee farms,” he noted.

Reports at the time indicate that in the wake of the protests, the head of Honduras’ energy commission announced that CABEI had frozen funding for 14 projects — totaling around $300 million — but not Babilonia.

The head of the commission, Jack Arévalo, told local media that the dam had the right permits and any stoppage could result in the government having to pay Energisa compensation.

Despite the litany of problems with the dam, Energisa completed building Babilonia. A month after Ulloa finished his term as mayor of Gualaco in January 2002, he said his replacement granted the dam an operating permit.

"In two hours, the leaders, along with a mayor, managed to reverse what we had fought for four years," he said.

People living in the area told reporters that they are already seeing negative environmental effects from the dam. Ulloa said the river where it was built now flows at around half its previous level.

“The project is not self-sustainable, it depends on the flow of the river,” Ulloa said.

The Dark Side of Barro Blanco

A decade after the Babilonia controversies, CABEI agreed to loan $25 million to another controversial dam in Chiriquí, in western Panama, known as Barro Blanco.

Indigenous Ngäbe-Buglé communities from the area had long protested against the dam, arguing they were not properly consulted before the government approved the project, which would end up flooding nearly 260 hectares of land, displacing families, and drowning ancient cultural sites.

Initially, the European Investment Bank, the European Union’s development bank, had also agreed to provide financing for the $80 million project. But after several indigenous groups filed a complaint warning of the damage it would cause, the bank announced a formal inquiry into the project.

When the dam’s developer, Generadora Del Istmo, S.A. (GENISA) learned that this inquiry would include sending officials to see the site, the company withdrew its request for funding. In 2011 CABEI stepped in, alongside two other European development banks.

After mass protests, police responded with violent crackdowns, according to human rights groups, who reported officers had shot protesters with rubber bullets, went house-to-house pepper-spraying people, and slapped opponents of Barro Blanco with trumped up lawsuits.

Early in 2012 two protesters, Jerónimo Rodríguez Tugrí and Mauricio Méndez, were shot dead by police at one of the demonstrations. In a report to the United Nations Human Rights Council seven years later, indigenous rights non-profit Cultural Survival noted no one had yet been convicted of their deaths.

GENISA did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did Panama’s prosecutors’ office.

Just over a year after the pair were killed, in March 2013, the body of another protester, Onesimo Rodriguez, was found dumped in a stream. According to media reports and accounts from rights groups, he was murdered by four masked assailants after attending a rally against Barro Blanco.

An internal CABEI report from 2018, obtained by reporters, said the bank had “undervalued the environmental and social risks” of Barro Blanco when it agreed to fund the dam and started disbursing money before any environmental and social impact studies had been carried out.

‘Environmental Genocide’

CABEI continued to fund Barro Blanco after multiple environmental issues had been raised — and pressured authorities to restart construction after the government halted construction because of those concerns.

In January 2015, Panama’s National Environment Authority completed an assessment of Barro Blanco and its conclusions were damning. GENISA had failed to meet 20 measures laid out in the project’s management plan, including polluting the water and air, not properly disposing of hazardous waste, and failing to submit an agreement with local indigenous people.

The auditors recommended the project be suspended until GENISA “present[s] evidence of compliance with all environmental commitments," according to a copy of their report. CJI found the document hidden among the Pandora Papers, a huge trove of documents from 14 offshore service firms — including the law firm that represented GENISA — leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with media partners around the world.

Panama’s National Environmental Authority halted construction the following month.

However, the environmental concerns did not deter CABEI or its co-financiers, the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), and a subsidiary of the German KfW Development Bank.

According to a letter posted online by climate action watchdog Carbon Market Watch, the development banks wrote to Panama’s vice president in the following months defending GENISA and calling for the project to be restarted.

They wrote with “concern and consternation,” claiming the environment ministry had not given the company enough time to respond to the breaches. They followed with an ominous warning that the “actions such as the one taken against GENISA could weigh against the country in future decisions of investment and prejudice the flow of investment long term.”

Isabel de Saint Malo de Alvarado, the former vice president to whom the letter was addressed, said her government had tried to create inclusive dialogue with local people about Barro Blanco, but had faced pressure from GENISA and the development banks.

“The financing organizations and GENISA, who were well aware of our efforts which were public, pressed for a fast track,” she said. “I personally believe such [a] fast track was based on the idea that force could be used as had many times before in Panama, leading to people being hurt or even killed in violent confrontations with the police.”

“Inclusive development efforts need to be valued and supported if the region is to overcome its obstacles and developing financing organizations need to be on the side of the support to such efforts. I am not certain that in the case of Barro Blanco that has been the case.”

In May 2015, the same month the banks sent the letter, an independent panel from the Dutch and German development banks released its own audit of Barro Blanco, which found the lenders had “not taken the resistance of the affected communities seriously enough.”

Despite the many issues with Barro Blanco, Panama’s government allowed work on the dam to restart in September of the same year.

GENISA was fined $775,000 and told to “negotiate with, relocate and compensate those affected by the hydroelectric project” and address the violation of the social and cultural rights of the affected Ngäbe people.

Barro Blanco began operating in 2017. CABEI continued to profit from its loan to GENISA until 2021, when the company finished repaying it with interest.

Since Barro Blanco was finished, Ngäbe-Buglé indigenous communities have suffered. Several communities have been displaced, their lands have been drowned, and ancient cultural sites have been lost. Studies show the dam has had a devastating impact on the Tabasará River, killing off marine life.

Manolo Miranda, leader of the Movimiento 10 de Abril protest movement against the project, said massive fluctuations in the water level have made it virtually impossible for people to travel along the water course.

“There were no sanctions that we observed … despite the fact that it is required under Panamanian law,” he said. “This is environmental genocide for the communities and towns that tried to stop the project.”

“In Panama, justice is only served against the lower class,” he said.

Jonny Wrate (OCCRP), Danielle Mackey, and Sol Lauría Paz (La Prensa Panamá) contributed reporting.

Mariana Castro and Madeline Fixler are reporting fellows for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School.