Marcel Deschamps was desperate.

The Canadian factory worker had already been hounded for months by a succession of scammers who had wormed their way into his confidence, convinced him to invest large sums of money in fake crypto assets — but never let him withdraw a dime. Now he had barely enough left to buy food for his cat, or even feed himself.

Then the most recent scammer, who called herself Mary Roberts and claimed to be a professional crypto expert, phoned him again.

He had finally realized she was conning him too, and threatened to report her to the Canadian police. She broke into a shrill laugh.

“You are so laughy,” she crowed in heavily accented English. “You are so stupid. Even if you call the police of Canada, police of Quebec, police of Alberta, police of Calgary, police of Ontario, or the police of the entire world, you will never find my real passport. You’re fucking dumb.”

“Mary” was right that it would be difficult to track her down: She was a professional. The 26-year-old worked at a call center based in Tbilisi, Georgia, one of several revealed in the ‘Scam Empire’ investigation.

As per protocol, she had taken careful steps to cover her tracks when dealing with Marcel. The personal photographs she had shared with him were fake. The passport image she had sent him was fake. The name “Mary Roberts” was fake.

But now, after a six-month investigation into the investment scam industry — based on an extraordinary leak of 1.1 terabytes of data from inside the Tbilisi call center — OCCRP managed to identify Mary and many of her colleagues.

About the 'Scam Empire' Project

They all use bland pseudonyms — Mary’s coworkers include “Anthony Adams,” “Alexander Richards,” and “Carl Green” — and draw on an array of forged paperwork to pass themselves off as British, French, or Spanish “financial advisers.” But behind the scenes, they are all young Georgians: university-educated, multilingual, upwardly mobile, and hungry for money.

From their nondescript offices in the center of Tbilisi, this group of around 85 scammers and support staff brought in $35.3 million from over 6,100 “customers” around the world between May 2022 and February 2025, according to internal spreadsheets used to track incoming funds and office expenses.

Openly referring to themselves as “scammers” — skameri in Georgian — they posted on social media about their lavish holidays and high-end purchases. A few months after her angry confrontation with Marcel, “Mary” jetted off for a luxury holiday on a Greek island. Another top skamer arrived at her wedding in a helicopter, prompting online speculation in Georgia. “What millionaire’s wedding is this?” a commenter asked.

These public displays of wealth would also be their undoing. OCCRP and its reporting partners in Georgia, Studio Monitori, iFact, and GMC, managed to identify the skameri by linking their behind-the-scenes chats — especially references to vacations, cars, and spouses — to content posted online.

In the end, we even found Mary’s real passport. (She posted it on Instagram.)

“Mary Roberts” is actually Mariam Charchian, 26. She posted this image to her Instagram Stories as she was about to board a plane. Her name on an airline ticket can be seen peeking out of her passport.

And we don’t just know their names. We’ve gotten an inside look at their operation, and listened to recordings of phone calls in which they extracted as much money as possible from their supposed clients, from Canada to Estonia, Spain to Norway. We watched from behind the scenes as they celebrated each transfer their victims made, splashed out on expensive purchases, and encouraged each other to apply harsher and harsher tactics to squeeze their clients for more money.

In many ways, they resemble the young workforce of any tech company, and their Tbilisi call center is like any other trendy white-collar workplace, with exposed brick walls and brushed-metal decor. The operation is run by a company called A.K. Group, which is registered as a telemarketing firm and owned by a seemingly unremarkable 36-year-old Georgian woman, Meri Shotadze.

Staff complain about their hours and their bosses. They receive detailed performance reviews and are ranked based on the volume of sales they bring in, with an online leaderboard tracking who is most successful. Top performers can earn more than $20,000 per month, and compete for prizes like iPhones and BMWs.

But darker details creep into the picture.

The workers’ performance reviews focus on how good they are at lying.

When they are reprimanded by supervisors, it’s because they haven’t hounded their customers aggressively enough.

And woven into their internal discussions is a clear recognition that they are destroying people's lives.

'Get Up, Push Your Clients, and Get the Money Flowing'

Like most young office workers these days, the staffers at A.K. Group maintain a constant stream of back-channel online chatter as they work. In Telegram groups with names like ‘Back Office’ and ‘AK-ers’, they swap animated GIFs of Hollywood celebrities, local memes, and occasionally images of scantily clad women.

They talk about what to eat for lunch.

They complain about work.

They celebrate ‘sales’ with images of popping champagne or clinking glasses. (A slow-motion GIF of Leonardo DiCaprio clapping his hands in The Wolf of Wall Street is also popular.)

And sometimes, they break the rules. Despite strict instructions to refer to each other only by their fake personas, the high-spirited scammers occasionally slip up and use each other’s real names while goofing around online. “They’ll arrest us!” said one half-jokingly, after sharing a photograph of himself with two colleagues.

“Mary Roberts” chats along with the others, but she’s more circumspect. She largely refrains from sharing information about her life and deletes personal messages almost as soon as she sends them. (Her penchant for deleting messages seems to be an office joke — “Mary, don’t delete this or I’ll hit you!” said one colleague after sending a GIF from the movie Spiderman.) . When a picture of a naked woman is pasted into one chat, Mary responds with the virtual equivalent of pursed lips: “I hope this never happens at my husband’s workplace.”

Her office persona is that of a teacher’s pet. Not only does she follow the rules, she was for many months a star performer on the A.K. Group’s top team: Team Koen.

Team Koen, which brought together seven of the call center’s best agents, was personally led by “Kseniya Koen,” the pseudonym of a hard-driving woman who specialized in dealing with Russian-speaking clients.

Koen, or “KK,” as many people called her, was a demanding boss:

She enforced standards across other teams in the call center, the leaked chats show. In one discussion last year, she berated a colleague going by the name “Fabio Bravo,” who led a group of German-speaking agents, for not spending enough time calling "clients."

But Koen clearly had a soft spot for Mary Roberts, who often topped the call center’s daily leaderboards.

In February 2024, Team Koen was tasked with bringing in $420,000 for the month, with each agent assigned their own personal goal. Mary had one of the highest: $80,000.

“You know, I’m counting on you this month,” Koen texted Mary that month, after checking a spreadsheet of sales targets that showed the team had a lot of ground to make up.

Mary responded with a big red heart, as if to say, “I’ve got this.”

How the Call Center Was Organized

Unlike her prim workplace persona, the face Mary presented to her “clients” was emotional, intimate, and urgent. She usually described herself as a single mother with a young daughter named Alice. Sometimes she had elderly parents to support. Sometimes, she was a Polish migrant to the U.K. who had clawed her way into a career in finance through grit and determination.

The face she presented was also beautiful. Early on in her exchanges, she would find an excuse to send a photograph of what she supposedly looked like — a stunning olive-skinned woman with green eyes. (OCCRP journalists traced the image to the Instagram page of a Ukrainian model. Mary had an entire folder of the woman’s photos saved on her work computer.)

When her targets wrote back, she was quick and lavish with compliments. “You are very handsome,” she told one. “You sound not more than 40,” she told another.

Mary first got in touch with Marcel, the Canadian factory worker, in February last year — the same month she was tasked with bringing in $80,000 single-handedly.

By that time, a succession of other scammers from the Tbilisi center had already been in touch with Marcel, 59, who lives in the small rural community of Alexandria, about 100 kilometers east of Canada’s capital, Ottawa.

One, calling herself Veronika, had convinced him to make a small investment through a fake platform called “Golden Currencies.” (“He is very interested and motivated…wants to have investments for the future,” Veronika wrote in an internal note after she spoke to him.)

Veronika also noted that Marcel had been scammed before, and was having trouble recouping his lost funds, which he said amounted to around 200,000 Canadian dollars.

She was followed by several other colleagues, including some who pretended to represent Golden Currencies, and others who claimed to be a British regulator who could help him get his money back. Somehow, it never happened. Instead, he kept getting convinced to pay more, for the opportunity to recover his funds.

Images from the A.K. Group’s internal software show various agents’ notes on their contacts with Marcel.

Finally, Mary got in touch. She told him she was from “Blockchain” and had found his lost $200,000.

Mary quickly found an excuse to send Marcel an image of the Ukrainian model. He shared a selfie in exchange.

Messages sent by "Mary Roberts" to Marcel Deschamps, found in the Scam Empire leak.

“You look like a teenager !!!” she exclaimed.

That same day, Mary typed a note into the software the call center used to keep track of its targets: “he started to love me.”

Mary was “nice, kind,” Marcel recalls — and had all the answers he was seeking after having fallen prey to scams in the past. He was skeptical of her credentials, but she reassured him by sending him a scan of her passport. Finally, she convinced him that, if he sent her just a little bit more money, she could help him unlock his lost cryptocurrency.

“I trusted her,” he said later. “She sounded very convincing. And she said she was going to get my funds back. So she was asking back then for … money to release the funds.”

But after sending around 3,500 Canadian dollars and being asked for more, he realized he had been scammed. When Mary called him again, he confronted her, sparking the confrontation in which she taunted him that he would never track him down.

“You just fucked up my credit. I have not one fucking dollar to play with for my next two weeks. How the fuck am I supposed to live? I might as well fucking kill myself right now….” Marcel told Mary during that call.

"Okay, go ahead and kill yourself,” she retorted.

“I can scam anyone I want and it’s not your fucking business. Your life is ruined. And I’m so happy, because you are a terrible person."

Shopping Sprees and Greek Holidays

Two months after that chilling conversation, Mary Roberts was planning a trip to Greece. She chatted about her plans with another agent, the same “Veronika Nowak” who had previously been in touch with Marcel.

Mary didn’t open up to many people at the call center, but she and Veronika were clearly more than just colleagues. They frequently talked about work, complaining about their bosses. They mostly wrote in Georgian — but with each other, they sometimes added Armenian words.

And this relationship proved to be the key to unlocking the true identity of Mary Roberts.

Unlike Mary, Veronika was not particularly careful about hiding her identity — she left little bread crumbs all over the call center’s group chats. In one, she mentioned that she was 21 years old, and had gone to school in a town in Georgia’s far west, Ozurgeti, best known for its production of black tea. Another time, a colleague let slip that her real surname was “Charchian.”

Journalists started combing social media for women with this profile. We found a candidate quickly: Mariam Charchian, a woman from Ozurgeti with a penchant for posting images of herself wearing designer clothing in front of European travel hotspots. But her age didn’t fit — she was older than 21.

Then we realized that Mariam had a younger sister, Veriko.

The more we studied their workplace chats, the clearer it became that Veronika and Mary were not just colleagues, but sisters. That meant the Mariam we had initially found online was none other than Mary Roberts herself.

Veriko and Mariam, now 22 and 26, grew up in an ethnic Armenian family in Ozurgeti. Their social media profiles show that they lived modestly until a few years ago. When Mariam advertised for a roommate in 2018, she shared pictures of a sparse apartment.

But starting around two years ago, the sisters began posting conspicuous displays of wealth online, showing off expensive jewelry and high fashion acquisitions, like diamond-encrusted bracelets from Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels.

Images from the social media pages of Veriko and Mariam Charchian, showcasing their a globe-trotting lifestyle. Veriko and Mariam posted many of their acquisitions in their branded boxes, suggesting they were originals, but reporters were not able to independently verify this.

Veriko celebrated her 21st birthday in Dubai and her 22nd in Paris. Mariam racked up trips to Cyprus, Paris, Greece, Dubai, and Milan. “Dream shopping, done” she posted on Instagram featuring an image of a box containing a 6,000-euro Cartier bracelet.

And Veriko’s travels dovetailed neatly with what “Veronika” told her colleagues about her trips. When Veronika mentioned an upcoming trip to Dubai, Veriko Charchian posted images of herself in Dubai on Facebook. When Veronika said she was going to buy tickets to Greece, Veriko Charchian posted herself modeling designer clothing in Santorini and Mykonos.

Neither Mariam nor Veriko Charchian responded to detailed requests for comment on their work at the call center or their influx of wealth.

“I can’t understand why anybody can do that to anybody,” Marcel Deschamps said after learning of Mary and Veronika’s real identities during an interview with CBC/Radio-Canada at his home in Ontario last month.

Marcel was shown some of the social media posts showing the women traveling the world.

“They’re living a life of luxury,” he said ruefully. “And not sparing anything…. On my money.”

Unmasking the 'King' and 'Queen' of A.K. Group

Like the scammers themselves, A.K. Group has kept a low profile. From the outside, it’s as if the call center doesn’t exist. It has no website, and although it’s registered as a telemarketing firm, it doesn’t publicly advertise its work. There are no signs outside its main office on Kavtaradze Street in Tbilisi or an auxiliary office on Shartava Street.

And these addresses have no official link to the company. Instead, both offices are rented on its behalf by other companies that are owned by proxies — an internally-displaced person from the breakaway region of Abkhazia and his elderly mother in law. Internet bills are also paid by these companies.

Expensive Offices Rented By Impoverished Proxies

After invoices helped reporters pinpoint the location of the call center’s offices, an unexpected document found among the files helped uncover the name of the company operating it: a letter of recommendation lauding one employee’s performance at “A.K. Group.”

This clue got the ball rolling. Despite taking so much care to stay under the radar, A.K. Group had made a major oversight: A photo booth service it had used at its year-end party in 2023 automatically posted all the images online — as eye-catching animated GIFs.

These moving photographs were a gold mine for journalists, providing the final evidence we needed to confirm the real identities of around a dozen other Georgians who worked at the call center, plus the name of the call center itself.

They show pink lights illuminating a hotel ballroom as employees decked out in diamonds and sequins pose for photographs clutching whiskey bottles. Behind them, the undulating image of a giant corporate logo is projected onto a screen: “A.K. Group,” it reads.

They included Meri Shotadze, 36, who is pictured shimmying in a black lace dress in many of the GIFs. Although we already knew that Shotadze was listed as the owner of A.K. Group in the Georgian business registry, seeing her laughing and embracing the company’s staff in image after image made it clear that she was also involved in the life of the call center itself.

Posing alongside Shotadze in the GIFs was Akaki Kevkhishvili, 33, who doesn’t appear in any of the center’s paperwork but, it became increasingly clear, was running the operation behind the scenes. (He even appears to have lent his initials to the center’s name.)

Internal chats reveal that it is Kevkhishvili who decides on the workers’ salaries and whether they will be promoted. Agents call him “boss.” In company Telegram groups, he always uses the same profile photo: a lion wearing a crown.

He is also the one who moves money out of A.K. Group’s accounts, according to internal financial spreadsheets, which show him taking out over $130,000 from February to May 2024. He has a private security detail paid for by the company, the finances show.

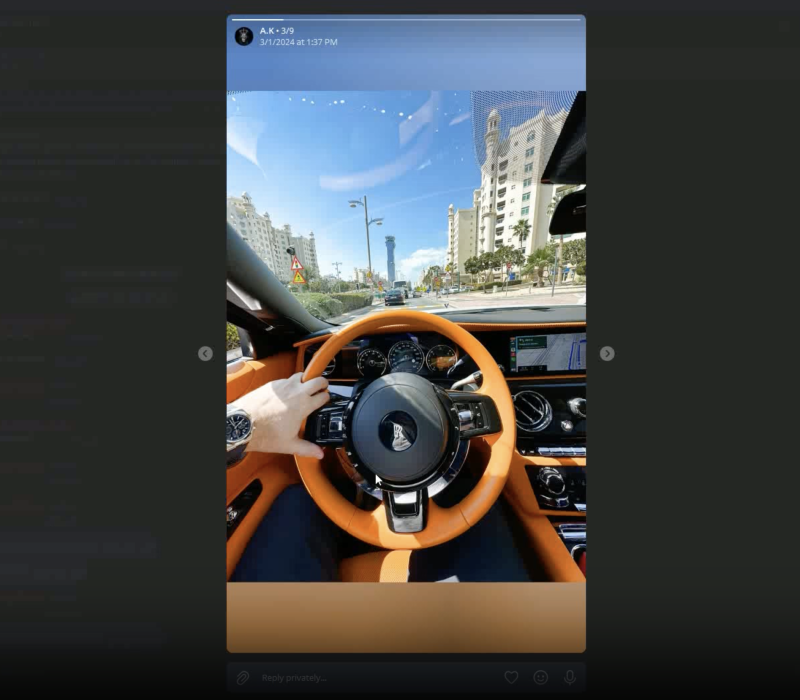

Today, Kevkhishvili drives a brand-new Range Rover, and has posted images on his social media accounts behind the wheel of a Rolls-Royce and a Lamborghini.

Akaki Kevkhishvili shared a photo on his social media account that appears to show him driving a Rolls-Royce.

But like the Charchian sisters’, Kevkhishvili’s wealth appears to have come to him recently. He doesn’t have a track record of owning any substantial property, land, or businesses in Georgia until 2024, when he purchased shares in two companies, one that makes furniture and one that trades in nuts. His family members also had no property holdings or business dealings until recently.

A New House for A.K.’s Mother

Older posts on Kevkhishvili’s social media pages show him posing with firearms and displaying eight-point star tattoos on his knees, a symbol of the post-Soviet criminal underworld.

If Kevkhishvili is the “king” of A.K. Group, Shotadze is its queen. Her Telegram handle also uses an image of a crown, and reporters found that she is personally close to Kevkhishvili.

Outside the call center, she is his business partner in the furniture company he co-owns. She is also the registered owner of a Range Rover with a personalized vanity plate incorporating Kevkhishvili’s initials, which reporters spotted parked outside his house on several occasions.

Her own car, a more modest Toyota, had its own personalized license plate that hints at her identity within the call center: “CO777EN.”

It turns out that it was Shotadze hiding behind the pseudonym “Kseniya Koen” — the woman who pushed staffers across the call center to work longer hours, and press their clients harder.

Meri Shotadze has fully embraced her call-center pseudonym Kseniya Koen, even using it as the basis for a personalized license plate for her car.

Internal conversations make it clear that in addition to enforcing standards, Shotadze helped Kevkhishvili manage the center, acting as a buffer between him and his sometimes querulous young workforce.

“Kaki is our boss. Sometime he will argue with us, sometimes he will be very gentle, [but] he loves his team,” she told one staffer who was upset after being reprimanded.

It’s unclear whether Shotadze and Kevkhishvili are the only people profiting from the A.K. Group or if there are other figures backing them. Neither of them responded to written requests for comment. When journalists attempted to confront Kevkhishvili at his home, security guards chased them away.

Georgian state prosecutors said they were looking into A.K. Group after receiving inquiries from journalists.

“In case of detection of any criminal activity, it will respond in accordance with Georgian legislation,” the office said in a brief statement.

Scammers Start to Cover Their Tracks

Until a few weeks ago, the skameri of A.K. Group were still enjoying the high life.

Their New Year’s Eve party to mark the advent of 2025 was even more extravagant than last year’s — it cost $107,000, according to internal records.. Hosted by two high-profile Georgian celebrities, it featured an elaborate cabaret performance with dancers in glittering headpieces and face masks writhing on stage and dangling from the ceiling. At the end of the night, an enormous cake was brought out, enveloped in gold and crowned with a spun-sugar diamond and the letters “A.K.” cast in chocolate.

They were also still scamming. “Mary Roberts” extracted $31,000 from elderly victims in early February, records show, while her colleague “Alex Davis” convinced a 78-year-old Canadian man to send him over $50,000.

But on February 15, OCCRP and partners sent detailed requests for comment to A.K. Group, Kevkhishvili, Shotadze, and other figures associated with the call center.

We still haven't had a response from any of them — but almost immediately after we sent our questions, clues to their identity started disappearing from the internet.

Meri Shotadze quickly deleted an image of herself wearing a Rolex watch, which we had asked her about. A few days later, she completely deactivated her Telegram account.

On February 24 and 25, she sold two apartments she owned in Tbilisi. She also jettisoned her CO777EN vanity license plate, according to state records, suggesting she might have sold her car as well.

Lana Vakhtangadze, also known as Lana Lehmans, the agent who had arrived at her wedding in a helicopter, shut down her Facebook account. So did Takhir Sultanovi, alias Barry Anderson, who took over leadership of the center's top "retention" team from Shotadze last year. Kevkhishvili's bodyguard deleted images from his Facebook account in which his boss appeared.

As for Mariam Charchian, Marcel was able to call her and confront her one day in mid-February. He asked if her family members knew what she did for a living, and reminded her of his name.

“Marcel? No, I don’t remember you,” she said.

“Are you Mariam Charchian? Or are you Mary Roberts?” he asked. She hung up. Still, he got what he had been hoping for: a sense that, for once, he had the upper hand on a scammer.

“I feel very good about that,” he said, relaxing in his kitchen after the call.

“I am a real softie and don’t hold a grudge against anybody, but … what she did to me, I know she is doing it to everyone else in the world. Hopefully it’s going to stop soon

“It’s fun to be on the other side of the table for once,” he concluded.

Marcel Deschamps turned the tables on his scammer by surprising him with a phone call.

CBC/Radio-Canada contributed reporting.