In 2014, Latvia’s beleaguered real estate market was booming again. Sort of.

The country had recently emerged from a brutal austerity program imposed as part of an economic bailout by the European Union (EU) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The economy was gradually expanding, and house prices were once again on the rise.

Nowhere was that more evident than in Latvia’s Golden Visa program, which provided residence permits to wealthy foreigners at bargain-basement rates. In 2010, the program’s first year, 289 people applied. By 2014, the number of applicants had increased to nearly 6,000.

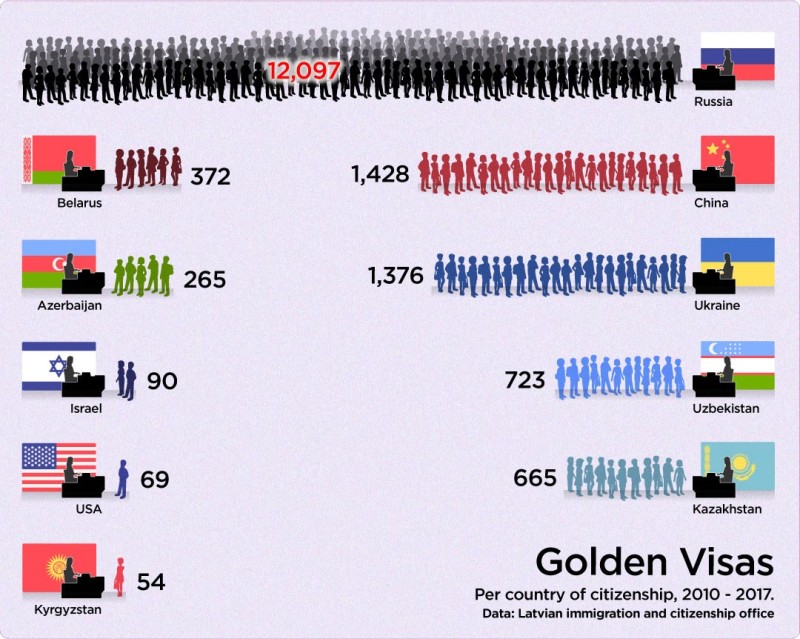

Real estate brokers were more than happy to serve the many Russians, Chinese, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks seeking an escape from their countries’ regimes -- or a place to hide from the prying eyes of tax inspectors.

Latvia had many advantages for this particular group of emigres. Most Latvians are fluent in Russian and Moscow is only 90 minutes away by plane. And most importantly of all, compared to other EU countries, Latvia’s “investors' program” was dirt cheap.

Foreigners could acquire the right to reside in an EU member state for an initial five years by paying as little as €71,150 (that is, if they bought a property in Latvia’s rapidly depopulating countryside). If they wanted to live in Latvia’s bustling capital of Riga or its surroundings, the price tag doubled to €142,300, still making the Latvian Golden Visa one of the best bargains in Europe.

As an added bonus, the tiny Baltic country's security services worried about their capacity to vet the flood of newcomers. Russia alone provided enough applicants to fill a smallish town -- 12,097 people, or more than two-thirds of the total 17,342 visas granted since the program began.

The numbers grew rapidly and peaked in 2014, the year that Russia annexed Crimea. What had begun as an economic development tool suddenly acquired renewed political significance. And if Latvians’ main concern about the program had once been the concurrent rise in property prices, some now began to ask how much was really known about these newcomers. A proposal was made in parliament to introduce quotas on their entry.

Over just one year, the number of granted permits plummeted, from nearly 6,000 in 2014 to 1,101 in 2015.

By the end of 2017, despite having brought €1.44 billion into the Latvian economy, mostly from property deals, the program had practically ground to a standstill.

“The best part of the Golden Visa program was the help it gave to stabilize the economy after the financial crisis in 2008 - 2009, when the property bubble collapsed and took quite a few industries with it,” says Janis Salmins, a specialist in the Latvian Ministry of Economy. “But to say it gave a massive boost of doing business or to wider economy: not really.”

Travel, not Trade

It wasn’t that there weren’t enough properties to go around; Riga's steeple-studded skyline is once again dotted with cranes. At the time of writing the homepage of Latio, one of the leading Latvian realtors, boasts around 1,300 advertisements which would allow buyers to qualify for a Golden Visa. Some Russian websites continue to advertise the Latvian program.

Vija Gailite, Latio’s head of sales, said the average Russian buyer was “a middle-class man, not extraordinarily rich, whose profession does not require his presence in an office, such as IT. They were buying for living or as an investment, to later lease [the property out].” An earlier story by Re:Baltica found that the visa was also popular with some Vladimir Putin's allies, such as Arkady Rotenberg, and managers of state-owned companies and subsidiaries, particularly those connected with the energy giant Gazprom.

Representatives of the Latvian immigration office recently told a hearing before a Latvian parliamentary committee that 70 percent of buyers simply wanted the right to travel and reside within the EU.

One of the factors behind the program’s collapse included a price increase to €250,000 in September 2014 -- still relatively cheap in the EU context. The economic recession in Russia, EU/US sanctions, and the fall in the value of the ruble did nothing to soothe investors’ confidence. Neither did the tighter security checks.

I-Spy an Investor

Ints Ulmanis, the deputy head of the Latvian Security Police, told a parliamentary committee hearing in December 2017 that those tighter background checks had turned up some troubling information.

“60 to 70 percent of all refusals are related to the risks of spying,” he told the committee. “Look at the source of the applications and how the secret services in those countries work. [For us] to let the people [into Latvia] and then to try to catch them would be absurd.”

Investigators also began examining applicants’ sources of income more rigorously. “The second reason is risk to economic security, as many of them cannot prove the legality of their money,” said Ulmanis. “We do not want as a state for international organizations to accuse us of the appearance of dirty money.”

Last but not least were applicants who had expressed “open hostility” towards Latvia -- such as making public statements that Latvia should be part of Russia -- but there have been just three to four such cases, he said.

According to a report by the Ministry of Interior, a total of 156 applications have been refused since the start of the program, about 100 of those since 2014.

Another 3,278 have had their Golden Visas revoked, for example when they sold the property that was the basis for the visa; withdrew the requisite money deposited in a bank; or failed to register in accordance with the immigration law.

The local chapter of Transparency International, Sabiedrība par atklātību - Delna, considers the real estate market to be one of the easiest routes for dirty money to enter the Latvian economy and calls on tax inspectors and investigators to focus on it.

Liene Gātere, the organization’s acting director, spells out why. “Criminals are well aware of the level of supervision. They have links with Latvian counterparts and information about what to do to in order to not get caught.”

Moving on

Viesturs Burkans, the head of Latvia’s anti-money laundering office, recalls three cases over the last three years when his office sought a criminal investigation of somebody engaged in the foreign investors’ program. In one such case, the person fraudulently borrowed money from a bank outside Latvia and invested it in property in the country. In another case, the seller of the property declared its value to be beyond the necessary threshold for a Golden Visa, when in fact half of the “investment” had been refunded to the buyer.

In the first half of 2017, only 64 applications for Latvian Golden Visas were submitted. Last November, the Latvian parliament changed the law to charge €5,000 for renewing a visa after five years, angering the local Russian expatriate community.

While citizens of other states have used Latvia’s Golden Visa program, almost 90 percent of applicants have come from countries in the former Soviet Union, predominantly Russia. Chinese citizens have also shown interest, though their numbers (just eight percent) pale in comparison to Russian applicants. Under those circumstances, a downturn in Russian applicants will likely spell the end of Latvia’s Golden Visa program. Besides, if a non-EU national had to choose, Latvian Golden Visas now cost as much as Greek ones -- where the winter climate is less punishing and the summers are longer.

Janis Adamsons, a parliamentarian from Harmony Party who was interior minister in 1994-95 and has retained a keen interest in national security issues, said the writing on the wall is clear. “The program will die,” he told a parliamentary hearing.

This story was produced as part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a partnership between OCCRP and Transparency International.