Javier Ortega’s press card was the only belonging found alongside his body in late June 2018. It had been buried in a pit in a southern Colombian jungle for 68 days. Although the card is badly deteriorated, Ortega’s family still cherishes it. To remove the stench, his father Galo could think of nothing better than to leave it in chlorine for a few days. Though it now has taken on a whitish hue, the murdered journalist’s face is still visible.

Galo said goodbye to his son on the afternoon of Sunday, March 25. "I was ill that day and didn’t have the strength to get up. That is the pain that I have with me,” he says. “On other occasions, I gave him a very strong hug, a blessing, and a little kiss on the cheek."

Ortega seemed unusually preoccupied. “He left worried and seemed sad,” Galo recalls. It was the last time he saw his son alive.

The next day, the 31-year old El Comercio journalist and his two colleagues, the photographer Paul Rivas and their driver Efrain Segarra, were kidnapped on the Ecuadorian side of the porous border with Colombia by former FARC guerrillas known as the Oliver Sinisterra Front. Nearly three weeks later, all three men were murdered.

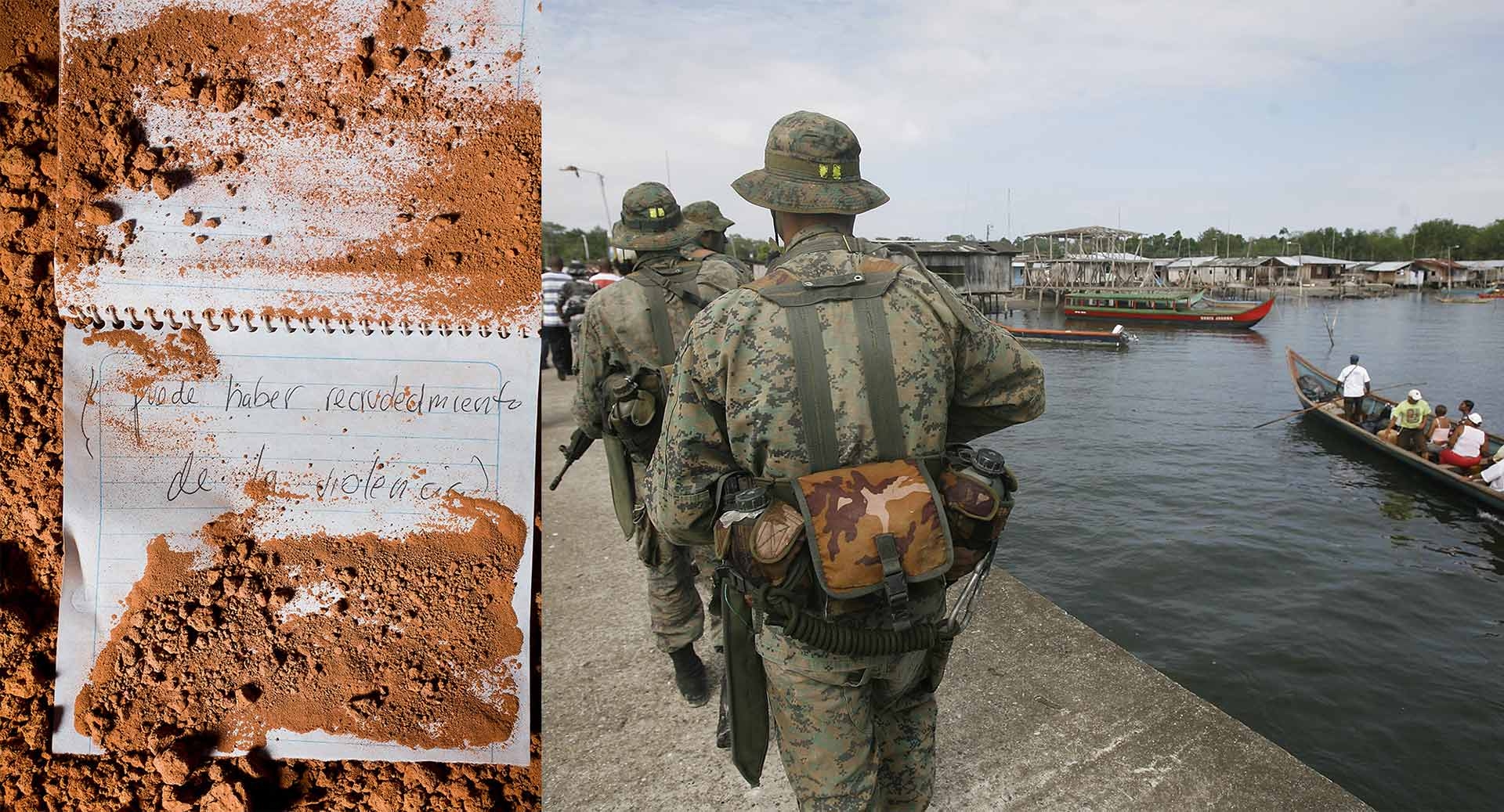

It was Ortega’s third trip this year to the restive Mataje River border region, home to the highest concentration of coca crops in the world, a booming and violent cocaine trade, and a mounting military campaign that’s fanning the flames (See: When Home Becomes an Armed Camp).

The Guerillas Who Wouldn’t Surrender

The Oliver Sinisterra Front is a group of about 300 fighters who operate in the porous border region between Colombia and Ecuador.

The young journalist knew the area well. After his murder, his father recovered about 30 notebooks Ortega had used in his work for El Comercio. They reveal meticulous reporting about the region, including prodigious notes on all aspects of the cocaine trade. Ortega had written about the double-hulled boats used to smuggle cocaine, manufacturing submarines to smuggle the drug to Central America, night-time shipments equipped with GPS receivers, and the fishermen who monitored the coast to alert the drug traffickers when the authorities showed up. Some of this material was used in a story published just two weeks before Ortega’s abduction.

He also wrote that Mexican drug cartels were active in the region. In late February, he even organized a Facebook Live session about the Sinaloa cartel’s doings in southern Colombia, and warned that the notorious criminal organization was “already operating in Ecuador’s border zones.”

One of the locals Ortega interviewed told him the drug traffickers “pay one million pesos (US$ 350) for information about whoever shows up here ... They probably even already know that you’ve been here.”

The WhatsApp Transcripts

But Ortega never got to publish what could have become one of his more important investigations, one about the existence of a secret communication channel between the Ecuadorian police and the Oliver Sinisterra Front, the same group that killed him and his colleagues.

The journalist, reporters have established, had been alerted by a confidential source that the police were conducting WhatsApp chats with members of the group. Their leader, Walter Patricio Arizala Vernaza (popularly known as El Guacho) was and is being hunted by both Colombian and Ecuadorian authorities. In the media, he’s frequently referred to as “Public Enemy No. 1.”

After his fateful trip to the frontier, Ortega had planned to dig deeper into this story. Though his colleagues were aware of the topic, they didn’t know all the details, and Ortega never obtained any transcripts of the conversations.

However, news of the communications channel did become public. In a press release allegedly issued by the Oliver Sinisterra Front, the authors both announced the deaths of Ortega and his colleagues and revealed that their group had been talking to the police. The affair became a national scandal for a country that had little prior experience with terrorism. In the outcry following the journalists’ murders, Ecuadorians were shocked to learn that senior police officials had been in regular contact with the perpetrators, who were well-known criminals.

Now, journalists have obtained from prosecutors a fuller set of the WhatsApp transcripts than were previously published. (Click here to read them).

Among other things, the message logs show the guerillas had threatened to attack civilians. Had the El Comercio team been informed of this, they may not have chosen to visit Mataje.

The secret communication channel had been opened more than two months before Ortega’s murder. Major Alejandro Zaldumbide, deployed to the frontier in 2016, said he received his first call from the guerillas at the end of February. A man with a Colombian accent dialing from an Ecuadorian number identified himself as a FARC member and demanded the immediate withdrawal of the Ecuadorian armed forces from the border.

A few days after this first contact, Zaldumbide was authorized by a top intelligence officer to continue communication with the guerrillas. The police major has said he filed 18 reports in which he detailed the messages exchanged between February and April.

Sometimes he talked with a militiaman who identified himself as Andres Sinisterra. On other occasions, he supposedly spoke with Guacho himself. The armed group repeatedly demanded the release of three of its men detained by the Ecuadorian military in January. They also advised Ecuador’s government to distance itself from antiterrorism agreements it had signed with Colombia.

In the chat logs, Zaldumbide offered the guerilla group a meeting with his superiors. He also promised to dispatch a government delegate to negotiate with them. But the chat logs suggest that didn’t happen, possibly because the authorities were concerned about the safety of their negotiators. As time passed, the tone of the exchanges grew more hostile.

In March, the guerillas became increasingly aggressive. After Ecuadorian police stormed what they said was Guacho’s mother’s house, he warned in an expletive-laden message that “For every single thing that was stolen from my family I'm going to launch an attack, even for the smallest thing you have taken.” He added: “Think as you like, but I'm losing patience. If I find a civilian at the border, I will kill him.”

On March 26, Guacho informed Zaldumbide that the rebels had snatched the El Comercio journalists as hostages.

Within days, on the advice of Ecuador’s Anti-Kidnapping Unit, a second communication channel was opened with another official. On April 15, Zaldumbide received a final message announcing another kidnapping: the abduction of Oscar Villacis and Katty Velasco, two Ecuadorian civilians whom Guacho accused of being undercover police agents. They were also killed.

Three days later, Zaldumbide passed his phone containing all the message logs to the Prosecutor’s office.

Though the police major had been authorized to speak to the guerillas, the interior minister — who resigned in the wake of the scandal — said in an interview that he never knew about the chats.

Zaldumbide has been called before the National Assembly to explain his actions.