It’s mid-April, a day before Orthodox Easter, and two undercover OCCRP reporters are waiting at a gas station in Romania’s capital, Bucharest.

Posing as businesspeople interested in buying masks to supply to hospitals, they meet a middleman, who directs them to another gas station, where yet more business associates arrive, first in a pint-sized Smart Car, then in a black Range Rover, then in a gray Audi A6.

The convoy then moves to a third and final gas station, where the reporters encounter Emanuel Daniel Dan. Known as “Manu the Bomber,” Dan is the son-in-law of Vasile Balint, a prominent figure in Romanian organized crime better known by the nickname Sile Cămătaru — “The Loan Shark.” His rap sheet includes burglary, theft, extortion, and kidnapping.

Dan — who was convicted of beating a member of the Romanian secret service with a chair in a restaurant — directs the convoy to a gated villa in a wealthy part of town. There, reporters are greeted by two Chinese men who show them into a living room strewn with boxes packed with 300,000 medical masks. Millions more are waiting in a warehouse, the sellers say.

The visit was just one glimpse into what European authorities say is a flourishing trade in counterfeit, substandard, and improperly documented products intended to protect people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Helping it all along is a parallel trade in counterfeit European quality and safety certificates, as well as gray market documents issued by companies that are not authorized to certify personal protective equipment (PPE).

These documents, while not technically illegal, are often misleadingly designed to look like they are conferring certification that the equipment conforms to strict European health and safety standards.

The Bomber and his business partners are among the traders using these shady documents to push their products. OCCRP and RISE Romania found their customers include at least four Romanian public institutions.

Sitting in the villa’s living room — decorated with a chandelier, a Chinese vase and a bright red sofa-and-chair set patterned with gold — Dan assures the reporters that the certificates are in order and the masks can be delivered in a matter of days. When they tell him they want to order a million pieces, he sits in stunned silence for a few seconds, then excitedly assures them that won’t be a problem.

“We have as much cargo as you need,” he says.

Too Much Paperwork

The masks in the villa were three-ply surgical masks produced by Dongguan City Xinyuan Nonwoven Co. Ltd., based in China’s southern Guangdong province. The company did not respond to a request for comment.

They were distributed in Romania by an electronics company with no background in medical devices or PPE called Evatech Electronics. Neither Dongguan or Evatech is included on the Romanian National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices's list of accredited mask providers.

Stopping the virus requires respirator masks classified as FFP2 or FFP3 under European standards, meaning they filter out 94 percent and 99 percent of airborne particles, respectively. Respirators are classified as PPE and so are subject to strict health and safety standards — verified by officially recognized companies known as “notified bodies” — before they can be given the CE mark that allows them to be sold in the European Union. As they offer less protection, surgical masks are subject to far looser controls than respirator masks.

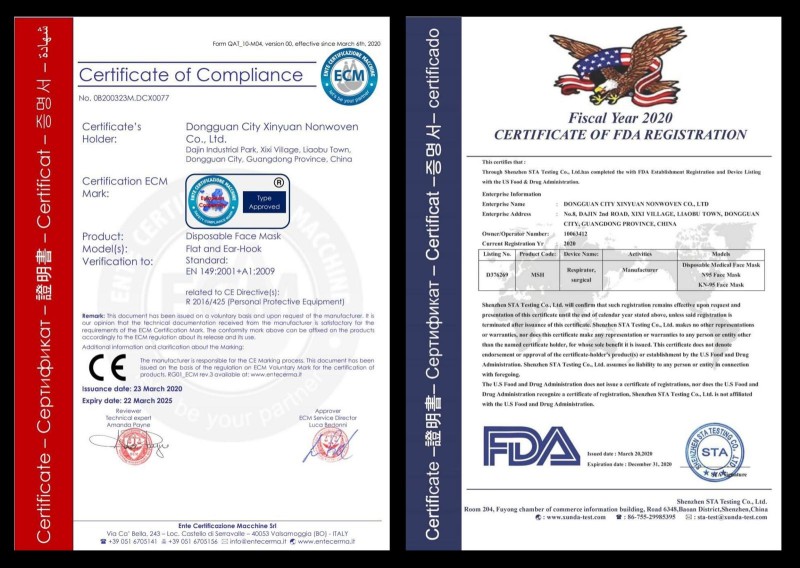

Following their visit to the villa, OCCRP reporters were sent a slew of false and misleading documentation for the masks by the sellers, including certificates that incorrectly stated they had been assessed as in line with Europe’s official standard for respirator masks. Dan could not be reached for comment.

Among the documents was a certificate from Ente Certificazione Macchine (ECM), a Bologna-based company that has issued dozens of misleading certification documents to importers of PPE and other masks. Despite not being recognized as a notified body for PPE, the company hands out certificates that, to the untrained eye, appear to confer a CE mark.

According to Dorte Kardel, a Denmark-based compliance consultant, the use of the documents is a common ruse to make run-of-the-mill masks that offer little protection appear to meet strict PPE standards.

“[The document] looks fantastic because it says something like ‘CE’ and ‘declaration’ and things like that but what you can’t see is that if this is medical equipment it won’t need a document from a testing facility at all,” she said.

ECM has been in trouble for handing out misleading paperwork before. In 2018, its certificates were cited in a case against a Chinese company that had sold scooters in Romania without the proper paperwork. Another document from the European Commission says ECM was investigated by Italian authorities in 2010 for certifying protective gear for fencing sports without the right accreditation.

ECM CEO Andrea Secchi said the company took no responsibility for problems with the products it certifies, but did not comment on the court cases. “ECM Italy is NOT responsible for the product, production, import, distribution, sale, advertising, technical assistance or consultancy, nor does it act as an agent of the manufacturer, he said.

Reporters also found similar masks being sold with a certificate issued by a Polish company that has been flagged for producing misleading documentation. In response to criticism, the company, ICR Polska, announced it has voided all certificates issued between March 1 and March 26 and claimed some of the documents carrying its name were fake.

On its website, the company lists the certificate number issued for the masks obtained by reporters as “invalid or fake,” but does not specify which. It also lists two other certificates for masks that were issued to the same company.

ICR Polska declined to answer questions sent by OCCRP. In an automated email, the company said its “voluntary certificates are not required by any legal act and are not equal to conformity assessment procedures restricted for notified bodies in that scope.” They also do not entitle a manufacturer to add a CE mark to their products, it said.

Dan and his associates also provided a certificate of approval claiming to be from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The FDA told OCCRP it “does not issue certificates for medical equipment,” adding that unauthorized use of its logo is a federal criminal offense in the U.S.

A Villa with a Storied History

As its name might suggest, Evatech Electronics started out as an electronics vendor. But it expanded to supplying medical and pharmaceutical products just two weeks before Romania declared a state of emergency over the coronavirus pandemic in March. In June, it changed its name to Eva Healthcare SRL.

The Romanian Commerce registry shows it is owned by 26-year-old Adina-Claudia Andrei. Her husband, Cristian Andrei, claimed Evatech had sold 18 or 19 million masks in Romania, including some to Romanian state institutions, almost all of them made by Dongguan City Xinyuan Nonwoven. He admitted using certificates from unauthorized providers, but claimed this is common practice.

“The masks I sell have a medical certification, except I couldn't sell them as a medical because I didn't have the approval from the Drug National Agency in Romania,” he told OCCRP.

“Everyone used certificates from ECM, ICR Polska or various companies that were not approved to issue protection certificates. Everyone sold like that. There's nothing wrong with it, as long as they were sold based on the manufacturer’s [statement of] responsibility.”

Adina-Claudia Andrei co-owns another company with Daiana Mihai, who was involved in a 2017 court case for allegedly selling counterfeit sporting goods. The following year, anti-mafia prosecutors said Mihai’s company was part of a criminal group specializing in tax evasion and money laundering. A trial in that case is still ongoing.

Mihai was also a shareholder in a company called White Gold SRL together with Gabriela Gao, who co-owns the villa where OCCRP reporters were shown the masks.

Gabriela Gao did not respond to requests for comment, but reporters found evidence her husband, businessman Gao Feng, also has a history of entanglements with organized crime and corruption.

Gao Feng, 47, was born in China but now does business in Romania, where he is known by the nickname “The Japanese.” In 2006, he was sentenced to a year and a half in prison for blackmail. An avid gambler, according to court records and press reports, Gao fell into serious debt in 2015 to the well-known fugitive gangster Sandu Peltz, who threatened him with violence when he was late to pay the money back.

Gao’s villa was also the registered address of three businesses run in part by his partner, Ni Jinming. Ni, who goes by the name Johnny, was tried, but acquitted last year over an alleged scheme to bring counterfeit goods into the country via the Black Sea port of Constanta. (Thirty-eight others were also accused in the case, including several senior officials.)

The land where the villa is located was previously owned by three businessmen, including Alexandru Vişan. In 2016 he was prosecuted for being part of an organized crime group, tax evasion and money laundering. That trial is still ongoing.

Online Ads and Government Contracts

The undercover reporters tracked the masks supplied by Evatech as they spread through the country.

According to Romanian public procurement records, Evatech sold over 35,000 masks to the water utility company in Olt county, the Jilava Penitentiary, the city council of Voluntari — a town near Bucharest — and Romania’s directorate for state properties.

Police in Bucharest’s Sector 1 also handed out Evatech’s imported masks to the public for free, according to local news and a recipient interviewed by OCCRP.

When contacted by reporters, the local police denied buying any masks from Evatech. The mayor of Sector 1, Daniel Tudorache, did not respond to a request for comment.

Reporters also tracked multiple online listings for the masks.

One listing, on the website enaturis.ro, shows two men wearing masks in what appears to be a warehouse holding a banner that reads, “We help Romania! Come on Romania! We’re together!” The ad lists the masks at two lei (46 U.S. cents) each, along with photographs of boxes and an image of the certificate issued by ECM, as well as a false claim that the masks are CE-certified and FDA-approved.

The pictures of certificates have since been removed. Sorin Badea, from enaturis.ro, said they had stopped advertising the masks because they had run out of stock, and argued that they should have been checked by customs.

“ECM is the certificate that the people we imported from gave us and [it] went through customs. No mask goes through customs until that certificate is checked,” he said. “Any mask which enters the country through customs [goes through a] certificate check, and if customs gives me a product release I have no reason to do any further research.”

The same photos and certificates appeared in several Facebook groups selling medical equipment. Reporters reached out via one advertisement to a man whose name on Facebook is Moș Crăciun, or “Santa Claus” in Romanian.

In communications through Facebook and WhatsApp, the man, who also goes by Teddy, told reporters posing as interested buyers that the masks were not surgical masks but had been purchased by doctors and hospital staff. He then shared an image of the ECM certificate via WhatsApp, as well as another one bearing the name of ICR Polska. Both documents purported to certify the masks as properly tested PPE, and bore a CE marking.

Asked to comment for this story, Teddy said he had bought the masks from a Romanian importer with “legal contracts,” but declined to say where. “I wanted to make a profit [during the COVID-19 pandemic]. It's the first time I've sold medical and protective equipment.”

“Do you think I am in trouble now?”

Additional reporting by Aubrey Belford (OCCRP) and Daniel Bojin (RISE Romania).