With prospects for democracy around the world seeming to darken just a little bit each day, it’s rare to come across unambiguous good news. This weekend, little Slovakia offered just that.

In an election local journalists have called a “referendum on the country’s future,” the long-time ruling party, tainted by scandal after scandal, suffered a resounding defeat. A neo-fascist opposition party that seemed poised to fill the gap fared poorer than expected. Instead, the surprise winner is a populist grouping led by a brash media mogul that has pledged, above all, to tackle corruption.

The bona-fides of this “Ordinary People and Independent Personalities” party, which was a minor player for nearly a decade before surging this year, have yet to be seriously tested. But regardless of how Slovakia’s new government performs, a more important transformation may already be underway.

The everyday hum of the institutional machinery that makes democratic governance possible — honest cops, independent prosecutors, impartial judges — seldom rises above the noise of a messy election. But if a judicial system is fundamentally corrupt, it’s no good simply voting in a new government on top. As Ukraine’s 2014 Euromaidan revolution showed, a true democratic spirit requires broad, sustained public demand for decent governance. There is evidence that Slovaks have demonstrated just that.

It began, as many such stories do, with a tragedy.

Two years ago last month, Ján Kuciak, a 27-year-old Slovak investigative reporter, was shot dead in a partially renovated home he shared with his fiancee Martina. She was murdered just seconds later by the same killer.

Because Jan was collaborating with OCCRP at the time of his death, we felt a deep personal connection to his case. In the weeks and months following his killing, we published a series of stories that continued his reporting and raised questions about the troubled murder inquiry.

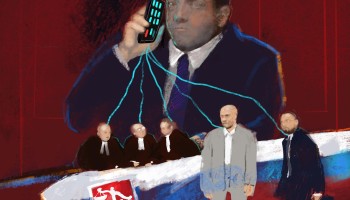

Two weeks ago, in collaboration with our Czech and Slovak member centers, we released the latest story in the series: an in-depth investigation into how the alleged mastermind of Ján’s murder, a wily businessman named Marian Kočner, used cash and kompromat to keep Slovakia’s justice system under his thumb for many years.

The report uses dozens of terabytes of police data that was made available to journalists, including chat transcripts from Kočner’s phones and documents from his computer. In an irony Ján may well have appreciated, his death has granted journalists unprecedented access to backdoor dealings of the kind he was so skilled at uncovering.

The details are as salacious as they are damning.

In a series of text messages, Kočner directed a lover to seduce high-value targets, such as politicians and prosecutors, with the goal of obtaining compromising information. The most influential people — “class-one sheep,” in the couple’s private lingo — netted her 30,000 euros.

Slovakia’s prosecutor general for seven years, Dobroslav Trnka, was also a pliant Kočner ally. And no wonder: Kočner installed a hidden camera in his office, bragged about bribing members of parliament to try to get him reelected, and threatened his life in a dispute over a secret audio transcript. It’s no surprise that the businessman was never indicted during Trnka’s stint as the country’s top prosecutor, though subsequent reporting by Ján and others — which used publicly available evidence — revealed that he had committed multiple financial crimes.

After Ján and Martina’s murders, at long last, Slovaks had had enough.

The initial public gathering on the following Friday was expected to be a small memorial march. It turned into a boisterous political rally of over ten thousand people. Protesters decried government corruption, which they knew Ján had been pursuing. They called for resignations. But most of all, they demanded an independent investigation into his killing.

When the official inquiry became tainted by a growing list of misdirections and baffling detours, public pressure grew. Each Friday, Slovaks around the country met at demonstrations dedicated to “a decent Slovakia.” They kept the scandal in the headlines. They added specific police officials to their list of heads that must roll.

And in the end, roll they did: First the interior minister, then the prime minister, and finally the police chief resigned within a period of two months.

Soon afterwards, the investigation began to pick up steam. Kočner was arrested and detained in relation to a long-simmering financial fraud case. The murderer and his three accomplices were arrested. And finally, this January, the closely-watched trial of Marian Kočner himself, now charged with ordering the murder, began.

It was of course Ján’s dogged reporting that led, the prosecution maintains, to Kočner’s decision to have the young journalist killed. It is no wonder: He had exposed a man who, using little more than money and shamelessness, had become Slovakia’s puppetmaster.

In OCCRP’s investigations around the world, we find again and again that corruption within the judicial system is the axis around which all other corruption revolves. So the fact that a man like Kočner now sits in a defendant’s chair is a real victory.

“A lot of people in the judiciary, in the police, in the prosecution … really felt the public pressure from the streets, and they started to work properly,” says Árpád Soltész, a local journalist who worked with OCCRP on the recent story. “You see it in the Kuciak investigation. Nobody believed it would ever be investigated or prosecuted ... It’s really a big achievement for civil society that Kočner is on trial.”

The aftermath of Ján’s murder has been a transformative time even beyond the trial. Zuzana Caputova, Slovakia’s young and liberal new president, stormed into the office on the back of the indignation that swept the country. And the grassroots organization that led the protest marches is still active two years later.

When they marched down their country's streets and squares, Slovakia's people showed that even the most moribund state institutions can be shaken into new life by public demand. Their story is a powerful reminder about what it is — beyond elections — that makes democracy live and breathe.