Reported by

Ján Kuciak, a young Slovak investigative journalist who was murdered three years ago, never got to the bottom of what could have been the biggest story of his life.

Long attuned to financial fraud and corruption, he was closely following the doings of Marian Kočner, a brash businessman who frequently appeared on television and in the tabloids to brag about his villas and sports cars.

In 2017, Kuciak had come across Kočner’s latest scheme: an attempt to get a judge to award him nearly 70 million euros from the coffers of a popular television station on the back of fraudulent documents.

Kuciak only had circumstantial evidence to go on, but in May 2017 he published an article describing how a judge had ignored key evidence to rule in Kočner’s favor. Nine months later, the young journalist was killed.

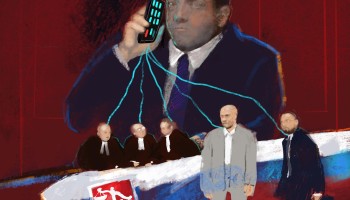

The powerful businessman was well aware of Kuciak’s reporting and had threatened him before. In March 2019, he was charged with organizing the murder of Kuciak and his fiancee, launching a legal battle that gripped Slovakia’s attention for months.

Ironically, though Kočner was acquitted of that charge (a verdict prosecutors are appealing), he did end up receiving a hefty prison sentence for the very fraudulent scheme Kuciak had been working to expose.

The young reporter would never tell that full story himself. But, using court documents, thousands of text messages, and interviews with police investigators, OCCRP and its Czech member center, investigace.cz, can now show exactly what Kočner did — and how he almost got away with it.

The scheme was simple, even “unsophisticated,” as the eventual guilty verdict put it. What Kočner relied on was not brilliance, but his connections within Slovakia’s judicial system. Using bribes, intimidation, and a powerful intermediary, he dictated the outcomes in this case and others that were important to him.

“What he was doing was made possible by the system,” said Jaroslav Láska, the police investigator who led the criminal investigation into Kočner’s fake documents. “The system and the political leaders that were here. It was his connection to politics, to justice, to everything — that’s what made him so strong.”

It was only after Slovaks cried out for justice in the wake of Kuciak’s murder that Kočner faced legal consequences after many long years of impunity.

And it wasn’t only him. Acting on evidence from Kočner’s seized cell phone, the police have carried out several major corruption investigations that have ensnared well over a dozen judges, prosecutors, and police officials. Now, just three years after his death, the thread that Kuciak started tugging has unraveled, revealing a system that was rotten to the core.

In response to requests for comment, Kočner’s lawyer Marek Para said that his legal team would appeal the conviction, and called some of the evidence against his client “not authentic and manipulated.”

An Old Friend

To extract 70 million euros from TV Markiza, a popular television station, Kočner turned to Pavol Rusko, a cash-strapped childhood acquaintance who also happened to be the station’s longtime co-owner and director.

In 2005 Rusko suddenly sold his last shares on the cheap and subsequently encountered financial difficulties, declaring bankruptcy in 2012. Kočner helped out his old acquaintance by buying the bank’s claim on his house and letting him keep living there. Shortly afterwards, their scheming began.

Kočner got ahold of a printer and paper manufactured around the year 2000. He used them to create false promissory notes indicating that he had loaned Rusko nearly 70 million euros that year. The notes said the debt was “guaranteed” by TV Markiza.

As the station’s former director, Rusko signed the notes and testified to their veracity. But because he was bankrupt and had no savings, the obligation to make good on the fake debt would fall to TV Markíza. Kočner sued the station in 2016 for refusing to pay.

His case did not seem strong. Kočner was demanding the repayment of a massive loan that had supposedly been issued without anyone but him and Rusko ever knowing about it. TV Markíza’s general director testified that its accountants had found no evidence of any deal having been made with Kočner. The station’s lawyers also pointed out that Rusko’s signature on the promissory notes was very different from the one he used on other documents in 2000.

Police investigators would later find at least six expert analysts who confirmed that the promissory notes were fake.

Kočner needed to ensure that such evidence would not be heard in court. He turned to Monika Jankovská, a former judge who had risen to the position of deputy justice minister. With her senior position, extensive connections, and love of luxury accessories, she was the perfect lever.

Jankovská would later deny any relationship with Kočner. “I don't know him, I did not communicate with him, neither directly nor indirectly,” she said at a press conference. “Not in person, nor through a middleman. In no way.”

But the evidence says otherwise. Encrypted text messages extracted by the police from an app used by Kočner show that Jankovská was an invaluable ally and intermediary. In the ten months leading up to Kočner’s arrest in June 2018, he and Jankovská exchanged over 6,000 calls and messages.

Jankovská also happened to be the mentor and former supervisor of Zuzana Maruniaková, a new and inexperienced judge at Bratislava’s fifth district court who had just been assigned to hear one of Kočner’s suits against TV Markiza.

Later, after being detained by police, Judge Maruniaková described Jankovská’s insistent campaign to pressure her to rule in Kočner’s favor.

“She helped me many times, especially when she found doctors for my seriously ill mother,” Maruniaková said. “I always respected her instructions, though I sometimes disagreed.”

Maruniaková said Jankovská first approached her shortly after she was assigned the Kočner suit. The case was easy, her former boss assured her, and the promissory notes genuine. “I won’t trick you into some bullshit,” Maruniaková recalled her saying.

Kočner’s messages show that Jankovská was acting on his instructions.

Fearing a less auspicious hearing for his claims after the 2020 parliamentary elections, he wanted to rush the trial.

Kočner believed he had everything ready, including bulletproof evidence.

“Jankovská urged me to set a hearing date as soon as possible, preferably for September 2017, and to make the ruling at this first hearing,” Maruniaková later testified. “I didn’t feel ready, so we agreed to set up the first hearing on February 8.”

Three days before the hearing, Kočner wrote Jankovská again.

Jankovská then paid a visit to Maruniaková’s office. “She was very upset and unpleasant,” Maruniaková said. “She said that she always helped me and my family. And that, depending on what I do on February 8, she’ll decide whether she’ll turn the page and forget about my ‘misbehavior.’”

“I told her that I was scared. And she answered that I should be scared only after [the ruling].”

Jankovská’s messages to Kočner confirm that the two were waging a campaign of intimidation.

But despite the pressure, Maruniaková did not issue a ruling at the first hearing on February 8, later explaining that it was not her “normal practice” to do so. Kočner had to wait until the next hearing, which was scheduled for Thursday, February 22.

That morning, an anonymous bomb threat forced all the courts in Bratislava to be evacuated. TV cameras captured Kočner pacing in front of the building and talking on his cell phone.

Prosecutors would later establish that, by that time, he’d known for several hours what the rest of the country would not learn until the following week: The previous evening, Ján Kuciak, the young investigative reporter who had been hot on his trail, had been murdered along with his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

When their bodies were found four days later, the news made international headlines. Growing protests would eventually lead to the resignation of the prime minister and other officials.

But Kočner was still thinking of his promissory notes.

In the end, his case took four more hearings to conclude. But on April 26, Maruniaková finally ruled in Kočner’s favor, declaring the promissory notes genuine.

The businessman was elated.

But TV Markiza’s defense team was adamant that the trial had been conducted unfairly, pointing to Maruniaková’s failure to admit key witnesses and expert testimony that would have contradicted Kočner and Rusko’s claims. Instead, she had relied on the analysis of a single forensic expert provided by Kočner himself.

Maruniaková later conceded that she had caved. “I do admit that during the trial, I was influenced by Dr. Jankovska, I was acting under her pressure,” she told police.

“As a young new judge, I didn’t handle the situation well. I succumbed to pressure and wasn’t acting rationally,” she said. But Maruniaková was adamant that her decisions had not been influenced by the promise of financial reward.

Messages between Kočner and Jankovská suggest otherwise.

In an appeal to the Regional Court in Bratislava, the TV Markiza team challenged the fairness of the trial. They also filed a criminal complaint against Kočner and Rusko. The case was assigned to an experienced investigator, Jaroslav Láska.

He had little idea what he was getting into.

On a freezing February morning, Láska met an OCCRP reporter in a park in the historic central Slovak town of Banská Bystrica to recount his experience. The tall, thin man was animated, his eyes sparkling, as he spoke about the Kočner case, which he says changed his life. But he’s glad that difficult period is over.

As he set to work, methodically collecting evidence to expose Kočner’s forgery, he realized he was being targeted himself.

“It happened to my son that he was followed by a car all the way from school to home,” he said. “He called me [when I was] in Bratislava, and he was alone there at home.”

Kočner had hired private detectives to track his family.

“I was just telling myself, you idiot, you put him in danger!”

Láska said that Kočner also hatched a plot to compromise him. “I was asked to meet someone,” he said. “This someone came with Para [Kočner’s lawyer].” Láska understood that the idea was for someone to publish a photo of the two men together to suggest that he was leaking information to Kočner. “I immediately turned and walked away,” he said. “That probably saved me.”

“I underestimated his influence and how far he was willing to go,” Láska said.

But he continued his work. On June 20, 2018, Rusko and Kočner were charged with counterfeiting, falsification, unauthorized production of money and securities, and obstruction of justice.

“We got intel that he was planning an escape, had a boat ready in Croatia,” Láska said. “We needed to act immediately.”

Commandos tracked Kočner down and handcuffed him as he was eating with friends at a Caribbean-themed bar on the shores of a lake outside Bratislava.

“Was he surprised? Well, you never know with Kočner. He has this poker face,” Láska said.

At their criminal trial, Kočner and Rusko’s legal teams continued arguing that the promissory notes were genuine, and had been confirmed as such by expert analysis.

Jankovská, arrested on March 11, 2020, along with Maruniaková and 11 other judges, denied intimidating her former subordinate. But Maruniaková started cooperating with police, admitting that she had made her decision under Jankovská’s influence.

Jankovská’s lawyer, Peter Erdős, declined to comment for this article, citing the ongoing court case. However, he noted that his client was not serving as a public official at the time of the promissory notes case.

In early 2020, Kočner was found guilty and sentenced to 19 years in prison. The sentence was confirmed by the Supreme Court on January 12, marking the first time the businessman had faced consequences in his long years of pulling the strings. His co-conspirator, Rusko, was sentenced to 19 years in prison.

Though Kočner is now sitting in a Bratislava prison, he has more court appearances in his future. He faces four more criminal and corruption charges, including ordering the murder of Kuciak and Kušnírová. (He was acquitted of that charge in September 2020, but prosecutors have appealed.)

Meanwhile, his arrest had a ripple effect across Slovakia’s judicial system. Police found text messages on his phone that went far beyond his exchanges with Jankovská. They led investigators to another senior judge, Vladimír Sklenka, whose communications with Kočner reveal the extent of his connections within Slovakia’s judicial system. After his office was searched, Sklenka decided to cooperate — and his testimony led to that network’s unraveling.

“I Told You He’s Cool”

As the deputy president of the Bratislava’s First District Court, Sklenka was useful to Kočner because he could influence a number of business disputes in which Kočner was embroiled. In 2019, Kočner’s phone contained over 9,000 messages he’d exchanged with Sklenka.

The judge was introduced to Kočner by an acquaintance, a businessman named Ladislav Mojžíš who promised him an informal meeting with the influential operator. Sklenka agreed.

The two men met in an empty conference room of a hotel in the forested outskirts of Bratislava. As they chatted about politics, Kočner gave Sklenka a scrap of paper with four case numbers on it. As a favor, he asked Sklenka to check on the status of the proceedings. Sklenka agreed, and was rewarded for his trouble — to the tune of 5,000 euros in cash.

“See, I told you he’s cool,” Mojžíš said of Kočner.

In another meeting at the same hotel, Kočner proposed a solution for secure communication.

“He asked me what kind of telephone I have, so I showed him my old Nokia,” Sklenka told investigators. “And he told me I need a different phone.” In short order, Kočner brought a used silver iPhone 6 from his car and helped Sklenka install Threema, his preferred secure text messaging application. From that point on, it was the only way the two men communicated, Sklenka said.

“Unlike the Other Judges, I Had No Fixed Rate”

Early in his useful new friendship, Kočner asked only for small favors. Sometimes he wanted to know which judge would be in charge of which case, or check on the status of court filings.

Sklenka seemed happy to oblige. In fact, he was such a font of information that Kočner sometimes felt overwhelmed.

Requests for larger favors soon followed, such as ruling in Kočner’s favor or asking other judges to do so. Soon Kočner was not just telling Sklenka how to rule, but bringing him the reasoning he should use, already written and saved on USB sticks.

“I was very busy and the reasoning was well written, so I took it and let it upload it into the judicial software,” Sklenka confessed.

In exchange, Sklenka received payments ranging from a few thousand to 100,000 euros per ruling, part of which was laundered through a company belonging to Sklenka’s wife.

“Unlike other judges, I had no fixed rate,” he said. “I never asked about the money in advance.” In total, he admitted to accepting around 170,000 euros from Kočner.

Sklenka was also the one who distributed Kočner’s bribes to other judges — not just cash, but also luxury items such as perfumes and handbags. And since his usefulness to Kočner was proportional to his popularity, Kočner came up with the idea of having him distribute gift boxes to his colleagues on Christmas.

The boxes were well received and Sklenka informed Kočner that his colleagues were grateful.

Thunderstorm

In his testimony, Sklenka exposed not only himself, but also 14 other judges whose decisions Kočner attempted to influence. But it went further than Kočner.

In 2020, the police launched three major operations — “Storm,” “Thunderstorm,” and “Weed” — in which they arrested 21 prominent judges, including the deputy head of the Supreme Court. They were accused of corruption and infringement on the independence of the courts, charges which in some cases also involved dealings with Kočner. Another constitutional judge resigned as a result of public pressure.

It wasn’t only the judges and courts. In November and December 2020, two former police presidents were also charged with heading an organized criminal group, abuse of power, extortion, and corruption. One later committed suicide in his jail cell.

The head and deputy head of the financial crime unit within the Financial Administration were also slapped with serious charges, including abuse of power, extortion, and support of a criminal group. Top prosecutor Dušan Kováčik, who earned the nickname “61:0” for failing to issue any indictments in the 61 cases he was assigned, was charged with organized criminal activity, corruption, and failing to prosecute men who were plotting the assassination of a police investigator.

These revelations took place in a Slovakia that had radically transformed. After the outrage caused by Kuciak’s murder, those who had once made Kočner untouchable started to turn away from him. By failing to keep his encrypted conversations with judges and prosecutors hidden, Kočner took down some of the most influential people in the country’s judiciary.

Meanwhile, Láska has moved on from the police force and is now working for Slovakia’s Judicial Council as an investigator of judicial corruption. Asked whether he thought the anti-corruption crackdown would continue, he said he didn’t know.

“But I hope it will,” Láska said. “I still have a few tips.”