Five years ago today, at approximately 8:30 p.m., an assassin approached a home in Velká Mača, a village in southwest Slovakia. When investigative reporter Ján Kuciak opened the door, he was shot in the chest. The assassin continued to the kitchen and shot Ján’s fiancée, Martina Kušnírová, in the head. It would be four days before their bodies were found.

I read the news from my home in Bucharest, Romania. I hadn’t met or heard of Ján. I remember being relieved at the time that it was someone I didn’t know. Maybe that sounds selfish or insensitive, but I knew other investigative journalists who had been murdered for their work.

But we did have a connection. Ján had been working on a high-profile investigation with Pavla Holcová, a Czech investigative reporter and colleague of mine at OCCRP. Pavla had been whisked into hiding by Czech authorities once the bodies were found.

OCCRP’s editor-in-chief, Drew Sullivan, called and asked me to visit the crime scene with two more of our reporters. I had made a film called "Killing Pavel," about the car bombing in Kyiv that killed Belarusian-born journalist Pavel Sheremet in 2016. The documentary had used a forensic analysis of CCTV footage to challenge the official police narrative and identify potential suspects. Drew thought maybe we could undertake a similar investigation into this case.

At the time, we didn’t discuss a film –– it was the furthest thing from my mind. That came later, and the resulting documentary has been seen by audiences and won awards around the world. Tonight, on the fifth anniversary of the murder of Ján and Martina, the film will be shown for the first time in their home country of Slovakia.

That day in Velká Mača, our reporting team went by foot and by car around the village, identifying every CCTV camera we could find. Some were on private houses and businesses, others in public squares, on the roads in and out of the village, and at gas stations. We mapped them all out to trace possible routes the murderers might have taken to get to Ján and Martina’s house.

We met with local officials and neighbors to ask if they had access to cameras, and we requested CCTV footage from the police, although they unsurprisingly refused to hand any of it over. The limited footage we eventually acquired did not uncover any relevant evidence, and we left town almost empty-handed. Driving back to the airport, I imagined that was the end of the story for me.

At home in Bucharest, I continued to follow the news about the fallout of the murders. They sparked the biggest protests in Slovakia since the fall of communism. The prime minister was forced to step down, followed by the president of the police. About seven months after the killings, the alleged assassins were arrested. Six months after that, a businessman named Marián Kočner, whom Ján had written about extensively, was charged with ordering the reporter’s killing.

Kočner’s trial was set to begin at the end of 2019.

The Leak

Almost two years after the murders, Pavla, my Czech colleague who had been working with Ján at the time of his death, received a phone call. An unidentified source offered her the entire murder case file. It was 70 terabytes of police evidence that included all the data from the decrypted phones of Kočner, the murder’s alleged mastermind.

The source was concerned the data could disappear. It would be safer with Pavla, outside of Slovakia.

Pavla told me about the leak: encrypted messages, conversations, and secret videos that showed how Slovak oligarchs, politicians, police and judges had been interacting in nefarious ways with Kočner and his intermediaries.

At OCCRP, we talk a lot about “captured states,” where oligarchs hold the levers of power over political systems. Journalists had always assumed Slovakia was a captured state, but Pavla thought she might now be able to prove it.

I never wanted to make another film about a murdered journalist, but this was different. It was the story of a brutal killing, but the new evidence Pavla had also offered a blueprint of corruption in a European Union country.

Pre-Production, February 2020

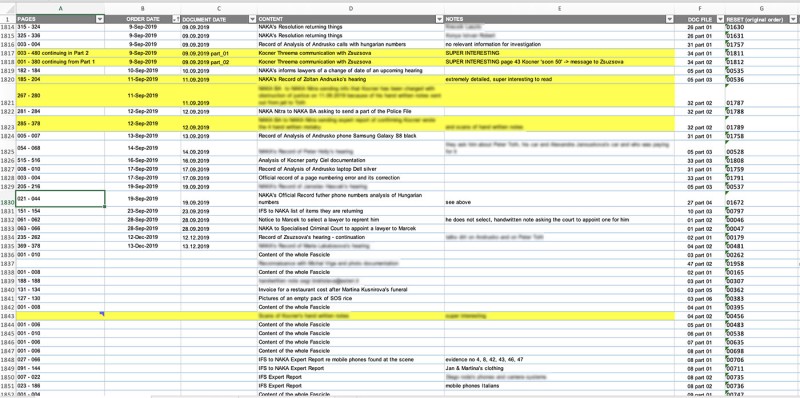

To deal with the sheer volume of evidence –– which included a 25,000-page police report, along with the 70-terabyte case file –– I brought in Slovak producer Julia Love Babuscak.

We set up in Prague, where Julia went through the massive police report, summarized each chapter in English, and created a timeline of every piece of the investigation. The result was a massive Excel spreadsheet that allowed us to rebuild the police investigation step-by-step and understand what had happened.

Our second base was in Bucharest, where OCCRP video editor Sergiu Brega organized the 70 terabytes of police evidence: crime scene photos, confessions, reenactments, phones, computers, thousands of hours of CCTV footage.

All of this organizational work had to be completed before filming could even begin. We needed to know the evidence, and understand what had happened, before we could ask interviewees about it.

Sergiu was key to identifying the evidence that we would use to visualize the investigation. In the end, archival footage and evidence from the police file made up nearly half of the documentary.

Filming, Summer 2020

Primary shooting took just 21 days, because of tight budgeting and time constraints. A verdict in the case was expected in late summer 2020, and we needed the subjects –– especially the lawyers –– to present their opinions and arguments without knowing what the outcome of the trial would be.

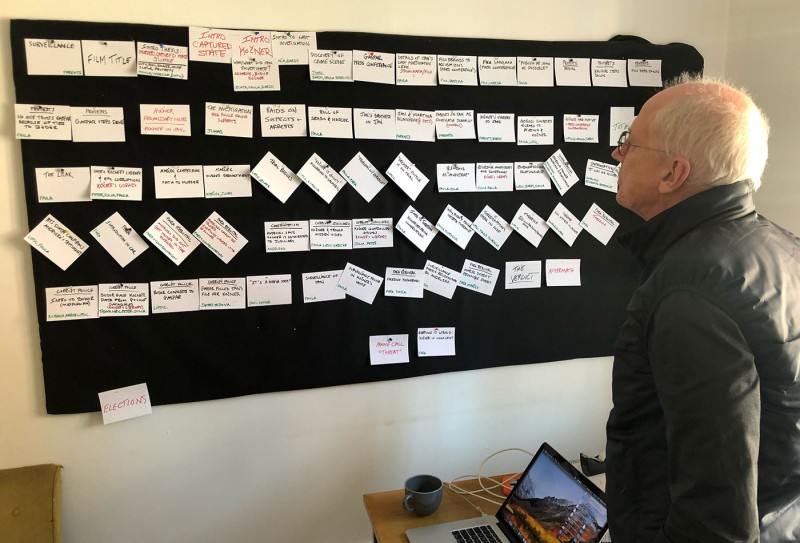

In a documentary like this, without narration, the overall story structure is planned before the camera comes out of its case. The characters need to narrate the story, so the primary characters are chosen and questioned to speak about certain scenes.

The lead police investigator describes the discovery of the crime scene and the police investigation. The sociologist narrates the political history and social consequences. The families bring Ján and Martina to life. The journalists explain the discoveries and consequences of the leaking of the case file. The lawyers present and challenge the evidence. And Pavla brings it all together –– the murders, the leak, the corruption and Ján’s legacy.

Access is paramount when making a documentary. Luckily, I had Eva Kubaniová, one of Ján’s good friends, on the team. Her participation brought a great degree of trust with the most sensitive characters, including the families of Ján and Martina.

One of the most important participants was Marek Para, the lawyer for Kočner, who was accused of ordering Ján’s killing. Julia, our assistant producer, was key in building trust between Para and the production.

In every documentary I have ever made, there is a point when you think it’s all going to come crashing down. For this film, that moment was in August 2020, the day after we finished our penultimate shoot. I got a call from Julia’s fiancée. She had died the previous night of a heart attack.

Julia had been the heart of the crew, and the film could not have been made without her. The film is in loving memory of her.

Editing in Copenhagen, November 2020

By November 2020, we had signed on as co-producers Final Cut for Real, a Danish company run by Signe Byrge Sørensen. Signe has extensive knowledge of the industry –– including securing funding, and bringing the film to festivals, broadcast and cinema release –– and she brought onboard a great editor, Janus Billeskov Jansen. We began editing in Copenhagen in November 2020.

We wanted this film to have a wide audience, so dramatic storytelling was key. The film really came together in the editing room.

It is composed of two stories.

On one hand, it’s a true crime thriller: police find a bloody crime scene. We take the audience through an investigation that leads to a complex chain of assassins and ultimately a controversial businessman. We follow the businessman’s trial, with compelling evidence presented from lawyers on both sides. The audience, whether they know it or not, is waiting to find out if justice will be delivered.

But we also needed to tell the political story, the story of the “captured state.” This was complex, involving history lessons, political intrigue, and police evidence, all showing how the corrupt system was built, and how it inculcated a callousness and disregard for human life that apparently led to the murders of Ján and Martina.

We told these stories together by alternating scenes between the true crime story and the “captured state” story.

The stories converge in the decrypted messages of the alleged mastermind’s phone. Journalists find messages that implicate both him, and the captured state, in the crime. Regardless of the verdict at the end, the bigger story is that the murder exposed the rot at the state’s core. The looming question is whether this reckoning will actually change society.

Premiere, May 2022

The film premiered in the International Competition at Hot Docs in Toronto, Canada, the biggest documentary festival in North America.

A few months later it premiered in Europe at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic. After the film, when the lights came on, the sold-out crowd turned to the families of Ján and Martina sitting in the balcony, and gave them a long standing ovation.

In 2022, the documentary was chosen to screen at festivals across North America and Europe –– including in New York, Chicago, Berlin, and Zurich –– and won a number of prizes.

The murders of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová were cold-blooded and evil. In the film I ask Pavla about Ján’s legacy. She says the tragedy is that his reporting is the reason all the deep rot and corruption was exposed. And it’s depressing that he can’t see it now –– he can’t see what he did, and how big his legacy really is.

Five years later I ask myself about Ján’s legacy and I worry: Are people too tired or overwhelmed to continue to care or to continue to fight? Are they too overwhelmed with disinformation to remember what Ján and his death exposed? I’ve always said this film is about the precariousness of democracy. I don’t want Ján’s legacy to fade away.