By the time he began trying to set up a Gambian bank in 2017, Arun Panchariya had already been sanctioned in his native India for market manipulation, banned for a decade from dealing with securities or accessing the capital market there, and fined in Dubai for lying to financial regulators.

And in Serbia, a major highway construction project was delayed for almost three years after Panchariya reneged on an agreement with the Serbian government to provide a feasibility study and disappeared.

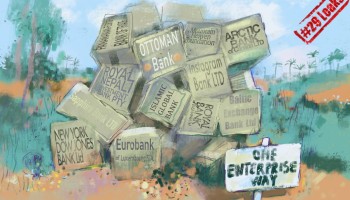

Nevertheless, the London-based company registration agent Formations House created and registered a bank for him in Gambia — or at least that’s what they told him.

A cache of leaked emails between Panchariya and Formations House, obtained by the information activist group Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared with OCCRP, sheds light on just how easy it was for a serial fraudster to gain a foothold in the offshore banking sector.

From setting up an address to doling out a license, staff at Formations House efficiently provided Panchariya’s proposed financial institution in Gambia, which he dubbed Global Suvarchase Bank Ltd., with all the trappings of an above-board business.

Formations House Responds

The current owner of Formations House, Charlotte Pawar, provided general responses to journalists’ questions about the company’s due diligence standards and about the origin and nature of the data used in this investigation. They are included below:

“There is no evidence that Formations House knew of Panchariya's checkered past — but it should have. Just months before taking him on as a client, the company had been warned by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the UK’s anti-money-laundering supervisor, for its failure to comply with due diligence regulations.

HMRC declined to comment on the outcome of its investigation into Formations House or follow-up actions taken, saying it was unable to discuss issues related to any specific business.

But the leaked emails show that less than a year after receiving this warning, Formations House owner Charlotte Pawar not only sold Panchariya what she claimed was an offshore bank, but even wrote to him personally with advice on how to make his business proposal look more legitimate.

When Panchariya sent the company a barely coherent proposal, full of inconsistencies and spelling errors, Pawar advised him to “think carefully.”

Noting that he had outlined an entity that combined banking, mergers and acquisitions, and investment services, she wrote, “A Bank would not offer everything under one roof, and typically seperates [sic] out firms for activities and partners in the delivery stages,” she wrote.

Unlike most of Formations House’s clients who were eyeing the Gambian offshore sector, Panchariya actually did go through the motions of obtaining a Gambian banking license.

But what Formations House did not tell him was that they were not authorized to set up banks or issue banking licenses in Gambia at all, and therefore his new bank would not be legally valid. In fact, it was just a shell company set up to look like a bank.

Formations House gave Panchariya what they claimed was a provisional license for Global Suvarchase Bank, as well as an address in Gambia’s capital, Banjul, in the course of one week in October 2017. Just over a month later, Formations House sent him what they described as a full Gambian banking license. In fact, the document had been manufactured by the company’s own staff.

It is unclear what Panchariya used his new Gambian “bank” for, though he did register a UK company using almost the exact same name under its ownership.

Panchariya told an OCCRP reporter he set up the bank to gain tax benefits and facilitate currency transactions, but he stopped the process after learning the license was not approved by Gambia’s government.

“If you have offshore banking it is always good to have a bank in Switzerland, to have a bank in Luxembourg, to have a bank in offshore,” he said. “This was the first location in the whole of West Africa which allowed...offshore banking; none of the other countries has actually introduced this kind of deal. That’s why it is good.”

Now, however, he added, Suvarchase “is completely shut down.”

Panchariya also claimed he had not violated any laws in India, saying the case against him was the result of a personal vendetta.

He added that his appeal is still waiting to be heard by the Supreme Court. “I have never manipulated anything,” he said.

Suvarchase still maintains a website, but it is riddled with spelling and grammatical errors.

In a section headed “Vision,” the website reads, “We Change to be a model institution in providing off-shore Private Banking Services to all Corporate & UHNI’s segment of the Global Market.”

Panchariya’s emails to Formations House were rarely as long as the extensive signature at the end of his messages, which included seven elaborate titles, including “consul general of Liberia to Dubai” and director of something called the Global Business Chamber of Commerce - USA, which OCCRP could not verify exists.

He also boasted in his email signature of being the supervisory board chairman of a company called G.I.D.C. Doo, which he made a point of noting was connected to the Serbian government.

In fact, G.I.D.C. was a troubled enterprise that never got off the ground. It was established in 2013 as a joint venture between the Serbian government and Panchariya’s Dubai-based company, Global Capital Advisors Management, to provide a conduit for the Arab investors to finance a highway construction project in Serbia

The government got as far as signing an agreement with G.I.D.C. five months later to complete a feasibility study and finance the preparation of technical documentation on a $27.3 million highway project.

Velimir Ilic, who was then Serbia’s minister of construction and urban planning and signed off on the agreement, described his observations, recalling a time when wealthy Arab investors were flocking to Serbia in search of investment opportunities.

“The guy [Panchariya] came accompanied by one of the [UAE] sheikhs,” recalled Ilic. “They convinced us that this guy would do these projects for free, like their donation to us. But whenever we called them to ask if anything had been done … no one answered.”

Speaking to Serbian media at the time, Panchariya hailed the highway as “a very important strategic project” that would connect Romania and Ukraine with the Adriatic Sea.

But Ilic said he doubted Panchariya’s intentions from the beginning, calling the Indian businessman “very suspicious” and over-eager to obtain official documents from the Serbian government.

“He cared very much about these contracts,” said Ilic. “He was constantly in the government offices, in the finance office … When he got the contracts and the documents from the government, he disappeared.”

He said he believed that Panchariya was either looking to launder money or obtain contracts that would help him raise capital in the United Arab Emirates. Nonetheless, Serbian authorities never officially investigated him for any of these crimes.

The deal collapsed in October 2016, causing a delay of almost three years in Belgrade’s plans to build a highway from the Serbian town of Pozega to Montenegro, since the government could not search for other investors while its contract with G.I.D.C. was still in effect.

Panchariya disputed Ilic’s account, saying G.I.D.C. had done the work they were commissioned to do and blaming Belgrade for the collapse of the project. He said he had lost one million euros ($1.1 million) in the process.

“Always the ball was in their court, not in our company’s court,” he told OCCRP. “The company was absolutely actively working, but since the government stopped responding ... we stopped.”