A one-year-old Mongolian toddler who owns part of a major coal company in the Gobi Desert. An eleven-year-old Azerbaijani profiting from state contracts with Turkmenistan and China. A Russian teenager who counted investments in Canadian and Californian pension systems among her billions of dollars of assets.

These are just a handful of the nearly 300 minors who owned or controlled significant stakes in Luxembourg companies as of 2020, an investigation as part of the OpenLux project has found.

While it is not illegal for children to own companies in Luxembourg, some of the names identified by OCCRP and its partners should have raised red flags. They included minors whose parents are oligarchs, criminals, and people with close ties to politically influential figures. A quarter of them were even younger than the entities they owned.

In 2019, Luxembourg published a register of “ultimate beneficial owners” — the true owners of companies, as opposed to proxies or nominees — for the first time, giving an unprecedented look into who has benefited from the country’s financial secrecy.

About the OpenLux Project

At the time, authorities offered a three-year exemption to any owners considered to be at risk of fraud, abduction, blackmail, extortion, or harassment if their names were published. That means the tally of minors is likely to be an underestimate, since children could easily request such an exclusion. A further 290 Luxembourg company owners were just 18 or 19 years old when they were declared to the registry, making it possible that they were also minors when they took ownership.

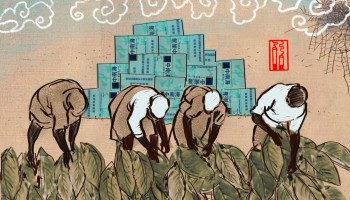

Why would children own companies, including some with many millions of dollars worth of assets? In a family-run business, parents might want to give their children shares as part of a long-term inheritance plan. But the fact that many were not even born at the time the companies were founded — and parents sometimes nowhere to be seen in company documents — hints at another possible reason: To add a layer of secrecy ahead of Luxembourg’s deadline to publicly declare assets.

Roman Borisovich, a transparency campaigner, told OCCRP that with inheritance plans you would expect to see trustees or others acting on a child’s behalf included in the registry.

“One-year-olds are not making decisions and running these companies.,” he said. “[I]t’s clearly smoke and mirrors [masking] the real owners."

Although the country’s banking regulators are scrupulous, he said, many Luxembourg companies exist only to hold assets abroad — meaning they aren’t subject to oversight from those regulators.

“Assets can be owned by six-months-olds, or by FBI most-wanted criminals. But nobody is checking as long as it's an asset and not cash. Everything else just goes straight under the radar.”

Luxembourg denounced the OpenLux investigations when they were published in February 2021, refuting allegations of shortcomings in its money laundering arrangements. But in August, the Ministry of Justice said it would put forward a draft bill to allow the registry to sanction those who abuse it for money laundering and tax evasion.

The reforms are among numerous efforts by the country’s government to clean up and strengthen its structures. In response to questions on the findings of this story, Luxembourg’s Ministry of Justice told OCCRP’s partner Reporter.lu that it intends to do an audit of all minors who are listed as company owners in the registry, with the results to be published later this year. But it also pointed out that many other countries allowed minors to own companies and that minors face the same scrutiny as adults.

Yves Gonner, the registry’s director, told Reporter.lu: “The regulations for a minor are the same as for an [adult]. We don’t do extra controls.”

”If a one-year-old can stand up in court and explain why his company has a right to privacy, then maybe I will accept it.”

Oliver Bullough

Author of ”Moneyland”

“That’s exactly the problem: They face no scrutiny,” said Maira Martini, an expert on illicit financial flows at Transparency International, which has been calling on Luxembourg and other countries to establish independent verification mechanisms and red-flag systems for cases like these. “Such registers are only as useful as the information they hold. OpenLux should have served as a wake-up call.”

Some in Luxembourg are pushing back against further transparency reforms, arguing they could violate the European Union’s right to privacy. But only a tiny subset of information reported to the register is made public, and that never includes personal data such as home addresses, Martini pointed out.

“The idea that a company should have a right to privacy is bonkers,” Oliver Bullough, the author of Moneyland: Why Thieves and Crooks Now Rule the World and How to Take it Back, told OCCRP. “It’s a fundamental misuse of what a company is for, which is to invest in and grow the economy. If you don’t want people to know how much money you have, don’t own a company.”

“If a one-year-old can stand up in court and explain why his company has a right to privacy, then maybe I will accept it.”

Azerbaijan

The Mammadov family enjoys all the perks reserved for the richest of Azerbaijan’s elite. Baylar Mammadov, his wife, and three children hold Maltese citizenship thanks to the island nation’s golden passport scheme, which would have set them back over 800,000 euros. His daughter’s star-studded 2014 wedding was attended by the Azerbaijani president’s daughter. The groom, Kamal Hajiyev, is the son of a member of parliament known to be close to the president himself. One of Mammadov’s sons has lived for years in England, where he attended a prestigious boarding school whose fees run as high as about 35,000 pounds per year.

Society columns in Azerbaijani media outlets have described Mammadov as a prominent businessman, without ever naming a business.

The OpenLux project, however, uncovered a clue: OCCRP found that Mammadov’s wife and children are owners of a Luxembourg-registered company called Canley Finance S.A., which has amassed investments and state contracts around the world since it was set up in 2008. As of 2020 the company is owned by Mammadov’s wife and his three children, who would have been 17 years, 9 years, and 3 months old at the time of incorporation. (Luxembourg provides no public information on corporate ownership history, making it impossible to know if the children did own the company then.)

Although Mammadov himself is not listed as a director or shareholder, he did loan the firm more than 21,000 euros to help get it off the ground, according to annual accounts.

Those accounts also show that in 2012 Canley Finance bought more than US$6 million worth of shares in Unibank, one of Azerbaijan’s biggest banks. At the time, the two youngest of the three children would have been 4 and 14 years old.

Canley Finance also owns a Maltese firm, Lenstor Enterprises Ltd., run by Mammadov. His son-in-law, Hajiyev, previously served as co-director. Since it was founded in 2008, the company has won more than $43 million in gas-related contracts with Turkmenistan’s government. Mammadov also owns a British company called Lenstor Trading LLP, which describes itself as a trading company specializing in energy, petrochemicals, and other sectors. Its clients include state companies in Turkmenistan and China, Russian manufacturers, and the largest ambulance provider in the U.S. state of Oklahoma.

In 2017, Canley Finance itself turned to the United States, acquiring two-thirds of a Florida hospitality venture called Buta Investment Group. The Luxembourg firm then poured $4 million into Buta, which claims to include the unusual combination of both KFC and Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Defence Industry as clients.

While it is legal for Mammadov’s children to own Canley Finance, the absence of their father’s name as an owner or even executive — apart from a footnote in one annual accounting document — raises questions about whether their names are being used to disguise the company’s real ownership.

Mexico

Miguel Zaragoza Fuentes, the founder of Mexico’s leading gas conglomerate, Zeta, is known as a private man. But his family life turned into a national soap opera in 2014 when his wife of 60 years and mother to his 11 children, Evangelina López Guzmán, filed for divorce.

López had discovered that her billionaire husband was in a relationship with a domestic worker named Elsa Esther Carrillo Anchondo, who had been employed as a maid by another of Zaragoza’s mistresses. Carrillo had given birth to Zaragoza’s twelfth child in 2004, and Zaragoza had subsequently transferred millions of dollars’ worth of assets — including cash, real estate, art, and an airplane — to Carrillo, her family members, and their secret daughter.

A divorce court in Texas, where Zaragoza and López were originally married, sided with López and ordered Zaragoza to hand her a significant chunk of his business empire. But after a series of appeals and legal battles that reached as high as Mexico’s supreme court, Zaragoza has not obeyed the order.

OCCRP has now found that one of the companies Zaragoza was meant to forfeit, the Bahamas-based Texas Gas & Oil (TGO) Ltd., is owned by Zaragoza and Carrillo’s now-teenage daughter. According to court filings, TGO — a supplier to Zeta Gas del Pacifico — had wired millions of dollars to Zaragoza and his second family for their personal use, including to pay college fees for another of Carrillo’s children. Last year, the supplier finally lost a two-year court battle in the Bahamas to keep its tax records a secret after Mexican authorities requested documents related to its sales to Grupo Zeta.

The company was just one of several Grupo Zeta-affiliated entities that Zaragoza’s 17-year-old daughter owns through two Luxembourg holding companies, Belgrave S.A. and Vaurigard S.A. Both had once been controlled by the Zaragoza family, but since at least 2019 — when Luxembourg made beneficial owners public — his daughter has been their sole owner.

Through Belgrave and Vaurigard, she is the beneficiary of US$73 million in assets, including stakes in 12 other companies in Peru, Guatemala, Spain, the Netherlands, the Bahamas, and Belize — eight of which she owns outright.

While some of these firms are known subsidiaries of Grupo Zeta subsidiaries, it is unclear whether the rest — or the Luxembourg holding companies themselves — were ever declared to Mexican tax authorities.

The Texas court declared that the two Luxembourg holding companies and TGO were both part of the Zeta corporate structure. Moreover, two of the companies owned by Belgrave and Vaurigard also share addresses and the legal representative of another Grupo Zeta subsidiary sanctioned by Guatemala for tax evasion.

Russia

For years, the identity of the owners of the Luxembourg-based company Felicity International S.A. proved too secretive for even French authorities to crack. In 2014, amid a probe into a multi-million-dollar fraud scheme, investigators wrote to the British Virgin Islands seeking information about the company’s founding shareholders.

Felicity had been incorporated by two offshore shell companies, one based in the British Virgin Islands and the other in Panama, but they had been dissolved in 2011. The trail went cold.

It was only in 2019, when Luxembourg compelled companies to begin listing their beneficial owners, that Felicity declared it was owned by three siblings with Bulgarian citizenship. At the time, the youngest was 15 years old.

OCCRP has since identified them as the children of Russian telecoms oligarch Sergei Adoniev, who obtained Bulgarian citizenship under the country’s golden passport scheme in 2008, then had it revoked in May 2018 after authorities there discovered his criminal record. In 1998, Adoniev was convicted in the United States of defrauding the Kazakh government out of $4 million through false sales of Cuban sugar.

In 1999, he was deported from the U.S. to Russia, where he was able to establish a telecommunications empire while receiving investment and support from various figures linked to the Kremlin and state-owned companies, according to OCCRP partner Bivol. In 2000, the LA Times reported that the FBI also suspected Adoniev of being behind a 1.1-ton shipment of Colombian cocaine seized at the Russian-Finnish border in 1993.

Felicity International was set up the same year Adoniev was deported — before two of its three current owners were even born.

According to annual accounts, the Luxembourg firm — and thus Adoniev’s children — are the owners of the 25-million-euro Villa Violettes, a four-story property overlooking the sea on a headland in Cap d’Ail on the French Riviera. Felicity bought the property in 2006, when the three were approximately 9, 3, and 2 years old. In 2015, the company also purchased a “computer database” for 450,733 euros, which today counts among Adoniev’s children’s assets.

Italy

The Italian film producer Daniele Lorenzano has long faced scrutiny due to his association with businessman and former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. He managed the acquisition of U.S. broadcasting rights for the now disgraced politician’s media empire starting in the 1980s.

Milan prosecutors would later establish that Lorenzano had also managed a globe-spanning tax-fraud scheme orchestrated by Berlusconi. In 2012, he was sentenced to three years and eight months in prison — just four months shy of the sentence handed down to Berlusconi himself — for his role in the fraud. In the end, neither served time after their prison terms were converted into community service.

In 1994, the same year Berlusconi launched his political career, a real estate company called Najis Real Estate S.A. was incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. It relocated to Luxembourg in 2003, bringing with it US$3.6 million worth of Moroccan real estate.

Stefano Martinazzo, a forensic accountant who consulted on the case, told OCCRP that he remembered the CEO of a Berlusconi holding firm testifying that “even the group’s top management were ‘distressed’ by the large fees paid to Lorenzano,” amounting to $20 million between 1994 and 2003.

It is not clear who owned the company at this time, but in 2019 it declared its owner to be a family trust set up by Lorenzano for his two daughters. By then, the daughters were in their teens, but at the time Najis first moved to Luxembourg, one had not yet been born and the other was just two and a half years old. . Trusts are a common way for parents to hand down assets to their children while avoiding the taxes and delays associated with inheritance. They are managed by third parties on behalf of the beneficiaries.

Today, Najis owns over two million dollars’ worth of property — and is $10.8 million in debt.

There is no indication that Najis or its assets were linked to Berlusconi’s tax fraud scheme. But if investigators had been aware of the entity at the time, they might have spotted a red flag: At least since it moved to Luxembourg, Najis has been under the management of Filippo Dollfus de Volckersberg, a Swiss nobleman who was himself indicted in a separate case in 2019 by a Milanese judge for tax evasion and fraud.

For anti-corruption campaigners like Borisovich, the problem is that Luxembourg companies are often used to hold assets such as property or foreign businesses, not just to bring money into the country, which he said was a more tightly regulated process.

“[But] if you have a holding company here, and the holding company acquires an asset, whether that’s a farm in Poland, or a mine in Mongolia ... that is ridiculously easy.”

Raul Olmons (MCCI), Ruslan Myatiev (Turkmen.news/OCCRP), Mika Velikovsky (IStories), Kelly Bloss (OCCRP), and Atanas Tchobanov (Bird.bg) contributed reporting.