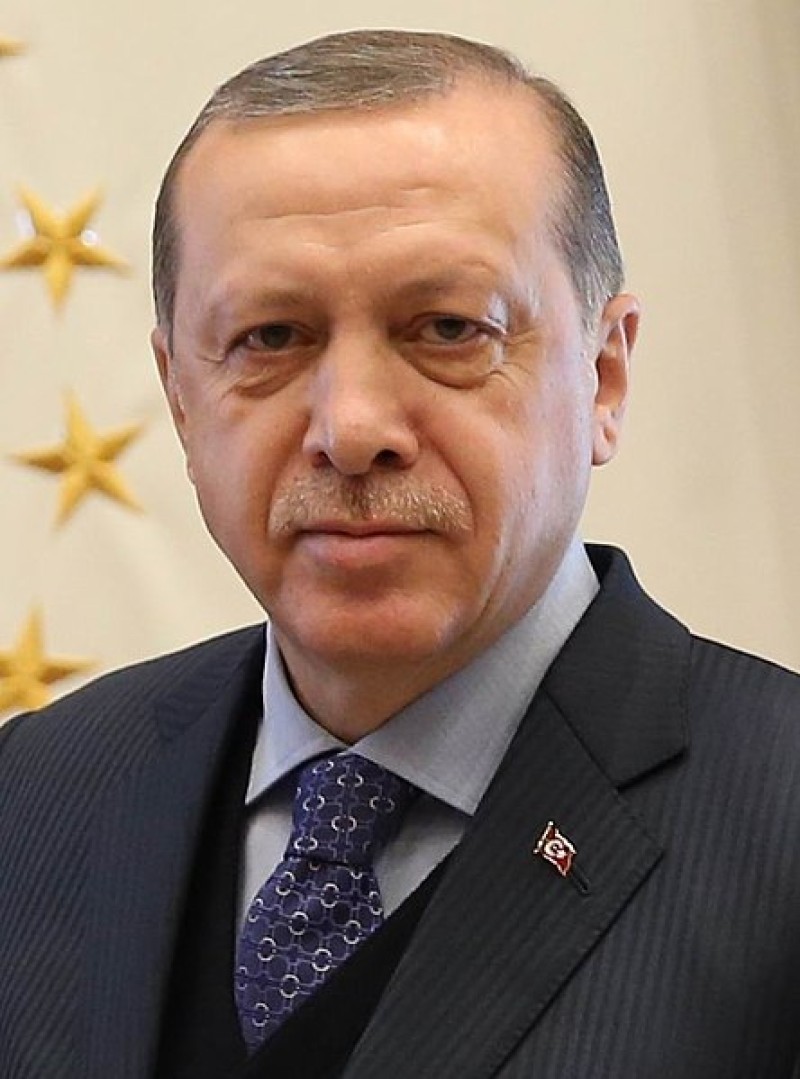

Rights groups accused the government of President Recep Tayiip Erdogan of capitalizing on the coronavirus crisis to shore up support from a far right party, which is connected to some of the convicts set to be released under a law Turkey’s Parliament approved this week.

“They seized on corona outbreak as an opportunity to secure convicted felons that will score points in their own constituencies,” said Abdullah Bozkurt, president of the Stockholm Freedom Center, a rights group focused on Turkey, in an email.

Many prisoners subject to release are members of organized crime syndicates associated with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) a far-right party aligned with Erdogan, according to Bozkurt, who worked with the popular Turkish news outlet Zaman until it was shuttered following an attempted coup in 2016.

Turkey’s Ministry of Justice did not respond to requests for comment submitted by phone and email. As many as 90,000 prisoners – about one third of the prison population – will be released under the law, which does not apply to roughly 50,000 prisoners convicted on “terrorism” charges.

Most in the latter group were detained indefinitely in the aftermath of the coup attempt, which rights groups said Erdogan used as an excuse to crack down on critics and political opponents.

Many of those swept up in the crackdown were charged with terrorism, and they include journalists and opposition leaders. Turkey now has more journalists in prison than any other country.

Countries including Indonesia, Iran, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have also freed prisoners in a bid to mitigate coronavirus outbreaks. Rights groups have urged governments such as Eritrea to release people detained for political reasons.

“Now, more than ever, governments should release every person detained without sufficient legal basis, including political prisoners and others detained simply for expressing critical or dissenting views,” UN Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet said in a March 25 statement.

Activists say Turkey has unfairly detained tens of thousands of people who are now at the mercy of a pandemic spreading through its prisons.

“Those convicted in unfair trials under Turkey’s overly broad anti-terrorism laws are also now condemned to face the prospect of infection from this deadly disease,” Amnesty International campaigner Milena Buyum said in a press release.

Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, asked publicly whether Erdogan was using the virus to eliminate imprisoned critics.

“Is their health not a concern, too? Or is his point to endanger them?” Roth posted on Twitter.

Bozkurt noted that prisoners not eligible for release under the new law include journalists who exposed the crimes of some convicts who will be freed – a situation he said benefited the government.

“It is a win-win,” he said.

Bozkurt accused the government of engaging in a “mafia tactic” to release members of organized crime groups associated with MPH, the nationalist party led by Devlet Bahçeli – a political ally of President Erdogan.

Bahçeli has a history calling for the release of certain criminals, including Alaattin Çakıcı, a high-profile convicted member of an organized crime group who he publicly defended after justifying his decision to pay him a visit while he was hospitalized in 2018.

In a 2004 trial, Çakıcı was convicted of several crimes including ordering the murder of his wife in front of their step-son. He was sentenced to over 36 years in a maximum-security prison.

Çakıcı is expected to be among the inmates who will be released.