The names were leaked to reporters earlier this year. In January, Direkt 36 and 444 received an envelope containing the names of citizens of Russia and several other countries, who, according to the anonymous sender, had received the permits, often referred to as Golden Visas.

The list includes four relatives of Sergey Naryshkin, the head of Russia’s foreign intelligence service (SVR). A successor of the Soviet-era KGB, the agency is tasked with gathering intelligence and conducting espionage activities outside of Russia. Before becoming the director of SVR in October 2016, Naryshkin served as the speaker of the Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, between 2011 and 2016.

Naryshkin himself did not apply, but permits were granted to his 39-year-old son, Andrey, who had worked for state companies but did not serve in politics, as well as Andrey’s wife and two daughters. The Hungarian Immigration Office confirmed that Andrey Naryshkin was one of its clients but declined to say in what capacity. The Naryshkin family did not answer journalists’ questions sent through various channels.

Also listed was Dmitry Borisovich Pavlov, a Russian businessman with close ties to the Kremlin who is active in charity and the Orthodox Church. Pavlov made headlines last November, when, at his 50th birthday party, an argument over parking turned into a bloody shootout, killing one and injuring five people. The Hungarian Immigration Office confirmed that Pavlov was one of its clients but declined to share further details. Pavlov did not respond to journalists’ questions.

Vladimir Blotskiy, a member of the Russian Duma, confirmed that he and his family members had received permits through the bond program before he became a lawmaker. He said the whole family gave up their Hungarian residency after he joined the Duma.

Iliaz Muslimov, a former Duma member, confirmed that he received a permit, but did not specify whether he did so through the bond program. Muslimov was a deputy between 2007 and 2011 for the pro-president United Russia political party.

Evgenii Evstratov, the former deputy head of Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear power company which is in charge of building Hungary’s new nuclear plant, also appeared on the list. Evstratov served as the deputy director between 2008 and 2011 when he was arrested on charges of embezzling 110 million rubles (about € 2.7 million).

A source close to Evstratov told Novaya Gazeta that after being released from prison, Evstratov applied for the Hungarian permit because he “wished to find a way to save himself” but he did not say whether Evstratov applied for Hungarian papers through the bond program.

The source claimed that Evstratov’s application was refused by the Hungarian authorities on the grounds that he was a “politically exposed person,” the term for public officials considered at higher-than-average risk of such crimes as bribery and embezzlement. Evstratov currently leads the state-owned enterprise Radiopriborsnab, which deals with the wholesale trade of electrical equipment.

Alexey Yankevich, the deputy head of Gazprom Neft, a subsidiary of state-owned Gazprom and the third largest oil producer in Russia, also received a permit, according to a source who did not wish to be identified. The source did not specify whether he did so through the bond program.

Andrei Kalmykov, head of a low-cost airline wholly owned by state-controlled Aeroflot, confirmed that he got a permit through the bond program. Kalmykov added that he applied for the convenience of traveling.

One former Hungarian security official questions whether all applicants were sufficiently screened. “From a national security aspect, it is remarkable and relevant if such senior political figures, state officials and their relatives are buying residency bonds in Hungary, with which they can travel inside the European Union,” said Ferenc Katrein, a former official of the Constitution Protection Office, the Hungarian domestic secret service.

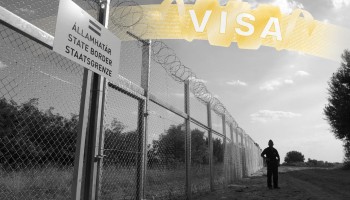

Director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) Sergei Naryshkin. Four of his relatives were on a list of those who had received Golden Visas.

Director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) Sergei Naryshkin. Four of his relatives were on a list of those who had received Golden Visas.

The Hungarian Golden Visa program

The law creating the Hungarian residency bond program was initiated by Antal Rogán, a powerful politician of the governing Fidesz party and now the head of cabinet for Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. It was rushed through Parliament without substantial debate in 2012 and quickly became one of the most controversial initiatives of the Fidesz government.

Under the scheme, those who invested €250,000 to €300,000 in Hungarian state bonds were granted a Hungarian residence permit. Other European countries have similar Golden Visa programs which offer residence permits or even citizenship to foreigners in exchange for investment. Press reports have revealed that Russian businessmen close to Russian President Vladimir Putin obtained similar papers in Cyprus and Malta.

Hungary’s program differed from the Golden Visa schemes of most other countries in that applicants could get their money back: the investment was placed in a special government bond that would fully repay the amount after five years.

The most heavily criticized aspect of the program was that foreigners did not invest in the residency government bonds directly but did so through designated intermediary companies with opaque ownership structures, handpicked by the Economic Committee of the Hungarian Parliament, led by Rogán at the time of the program’s creation.

The bonds were a windfall for these companies, which charged service fees ranging between €40,000 and €60,000 per investor. Moreover, the companies were able to buy the bonds from the state at a discount. Hungarian journalists have discovered several links between the main beneficiaries of the residency bond program and Hungary’s political elite.

The program was suspended in 2017. During the four years it operated, the state handed out nearly 20,000 permanent residence permits for residency bond investors and family members. While Chinese nationals were the predominant customers, permits were also issued to hundreds of Russians and dozens of immigrants from the Middle East and Africa. The Hungarian authorities, citing privacy concerns, have been resisting calls for disclosing the names of the bond buyers.