Regina Martínez was a prominent journalist in Mexico, reporting on drug gangs and political corruption, when she was beaten and strangled to death in her home in 2012. The official investigation into her murder was deeply flawed and left many questions unanswered –– perhaps by design.

As part of an effort to reveal the truth behind Martínez’s murder, OCCRP filed Freedom of Information requests for the investigation files, and is making them public here for the first time.

The requests were made in 2020, when a group of media organizations carried out their own investigation as part of a collaborative project coordinated by Forbidden Stories. Journalists conducted interviews and combed through court documents, and published their findings in an award-winning report.

The information they found cast doubt on the theory put forward by prosecutors in Veracruz state, who had succeeded in convincing the court that Martínez was murdered by a drug-addicted male prostitute they claimed was her lover.

Martínez's friends and colleagues insist she did not know the man. And the only person ever convicted for the murder, another addict with a troubled background, has recanted his confession, claiming he was tortured into telling police he killed Martínez.

The documents available to download below highlight many inconsistencies in that case. The files are presented in chronological order, and are divided into sections corresponding with the different stages of the case as it developed.

Mexico is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists, with at least 120 murdered in the last 20 years, including Martínez. Rights groups have been demanding that prosecutors reopen the case and release their files on her murder, but they refused to do so until last year, when they had to do so in response to journalists’ Freedom of Information requests. In November 2020, in response to questions from OCCRP and Forbidden Stories, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said the case should be reopened.

First Steps

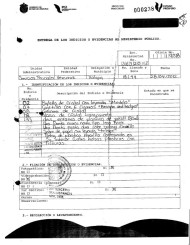

Investigators began by interviewing Martínez’s neighbors, as well as her brothers, about any notable events before the murder. One brother mentioned a recent break-in at the property, and investigators from the Veracruz Prosecutor’s Office said it had not been reported. Also included are documents describing how officers first discovered Martínez’s body, including a transcript of a call from a police officer at the scene.

The files contain a discussion about which agencies should control the investigation. The conversation included the Public Ministry, a federal agency that is overseen by the Attorney General’s office, which was also involved. The former Special Prosecutor for Crimes Against Freedom of Expression, which often investigates attacks on journalists, later said she felt she was being blocked by local authorities in her efforts to look into Martínez’s killing.

These files are heavily redacted to comply with Mexico’s Law for the Protection of Personal Data, which authorities often interpret as forbidding them from including photos and information that could identify any person at all. Even Martínez’s name was censored throughout, although the entire case file is about her murder.

Highlighted documents

Forensic Analysis

Investigators determined that Martínez had died from being strangled with a cleaning rag, and found blood in the bathroom where she had been beaten.

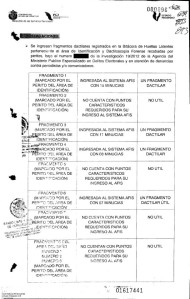

The files indicate that investigators found only “fragments” of fingerprints, but details about them are censored. More information was revealed in a separate investigation by Laura Borbolla, former special prosecutor for crimes committed against freedom of expression. Borbolla revealed that local investigators had ruined fingerprints. She also said she managed to recover two prints from the crime scene, but was unable to find a person who matched them — including the main suspect identified by Veracruz investigators, whose fingerprints were never found at the scene.

Highlighted documents

Disturbing Requests

The files include letters sent by the state Attorney General’s Office to summon people to testify. The letters informed the interviewees that they would also be fingerprinted and have DNA samples taken from their fingernails and mouths. Some of Martínez’s colleagues later told reporters that they were disturbed to have been treated like suspects, and had even been subjected to dental exams to determine whether their teeth matched a bite mark on Martínez’s body.

Highlighted documents

Corrupt Officials

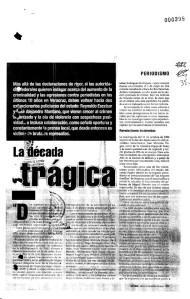

Journalistic articles about the killing of Martínez are included in the documents, along with investigative reports about corrupt public officials. Some of the articles were written by Martínez herself. Also included was “The Tragic Decade," an article published days after Martínez's murder that mentions two Veracruz officials as possibly having links to organized crime.

Also included in the files are requests from investigators to visit the homes of people who testified, as well as notes on Martínez’s friendships with fellow journalists.

Highlighted documents

Leads Not Taken

The Veracruz Attorney General's Office states that “it is the duty of this Specialized Prosecutor's Office to investigate the journalistic work of the deceased.” Martínez’s employer, the Mexico City-based Proceso magazine, also pushed for investigators to look for a motive related to her work.

Yet authorities failed to pursue that obvious lead, opting instead to make the case that her killing was a crime of robbery and romantic passion.

The files include a detailed description of Martínez’s home, including each room and its contents. Investigators note the presence of beer bottles.

Highlighted documents

Flawed Investigation

Borbolla told OCCRP that the Veracruz Attorney General’s Office conducted a flawed investigation. “Really, the local authorities were unaware of good practices and correct investigation protocols,” she said.

This section of the files includes official letters between local and federal authorities about the investigation.

Highlighted documents

Looking Away

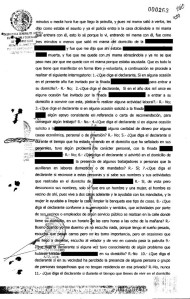

Ignoring the obvious line of investigation, investigators did not look at Martínez’s journalistic work as a possible motive for her killing. Instead, these files show, they asked for a psychological profile of her, which was prepared by a psychologist from the Veracruz Attorney General’s Office.

This section also includes reference to a request from the National Human Rights Commission regarding progress on the case.

Highlighted documents

Questioning the Family

Investigators questioned Martínez’s friends and family members about her private life, including romantic relationships. All responded that Martínez had been very reserved. The only relationship she was known to have had was with a photographer, years earlier.

The files show that investigators asked whether Martínez owned the house she lived in, and that they offered family members psychological support.

Highlighted documents

Handwritten Lists

Some documents were handwritten, including a list of items found inside Martínez’s house. The files also include people interviewed about Martínez’s work, including journalists, friends, and family. No interviews with politicians or public officials are recorded.

The files also note the measures investigators took to look into Martínez’s financial history.

Highlighted documents

A Quiet Life

Authorities tried to determine who Martínez had been in contact with. They searched phone records, and questioned friends, acquaintances, and fellow journalists. The files show that investigators made little progress, with interviewees telling them that Martínez kept to herself.

The document also notes that investigators were unable to obtain full fingerprints from the crime scene.

Highlighted documents

Finding Focus

The files show that investigators zeroed in on Jorge Antonio Hernández Silva, known as El Silva, who confessed to the crime but later retracted the confession, saying he had been tortured. Investigators questioned El Silva and his male acquaintances, and some spoke about their lives in the social scene around Parque Juarez, in the Veracruz capital of Xalapa, where they used hard drugs and engaged in prostitution. Investigators went to pawn shops to search for objects that were missing from Martinez’s house, including a laptop and cell phones.

Download pages 1121-1300

Download pages 1301-1416

Download pages 1417-1547

Download pages 1548-1680

Highlighted documents

A Case Full of Irregularities

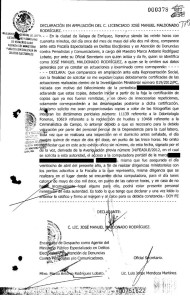

This section outlines the sentencing. Judge Beatriz Rivera Hernández accepted the prosecution’s argument that El Silva had come to Martínez’s home the night she was killed, along with a man called José Adrián Hernández Domínguez, who was known as “El Jarocho,” a slang term for someone from Veracruz. The prosecutor concluded that El Silva had intended to rob the journalist.

The case began to fall apart almost immediately. The investigation itself showed that many valuables remained in her home, making robbery an unlikely motive. El Jarocho was never found, and El Silva later said police had tortured him into confessing.

Judge Edel Álvarez Peña ordered El Silva released due to irregularities in the case against him. But one of Martínez’s brothers filed an injunction against the decision, and El Silva remains in prison.

The files also note that issues of Martínez’s magazine, Proceso, disappeared from newsstands on at least three occasions when it ran stories about organized crime, politics, and homicides.

Download pages 1681-1810

Download pages 1811-1940

Download pages 1941-2070

Download pages 2071-2148