One day in the summer of 2013, the central Moscow office of Fonbet, Russia’s largest sports betting company, looked like a besieged fortress.

Sparks and the smell of burnt metal filled the air. Officers from the anti-corruption directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs had come to execute a search warrant. Finding a barred door, they sawed it open using a grinder.

Before the search, investigators had used marked banknotes to place bets on tennis, soccer, and basketball matches on the company’s terminals. They found that Fonbet was providing online betting services using a website registered abroad. All forms of online sports betting were illegal in Russia at the time, so a criminal investigation was opened. Police found the marked bills and established that Fonbet was operating an illegal site. But despite the dramatic raid and apparent proof of wrongdoing, not much happened — except for a sudden change of ownership.

Today, Fonbet, with its network of brick-and-mortar locations and online services, remains Russia’s largest sports betting company. According to one advertising firm, it was the country’s largest advertiser during the 2018 World Cup.

Fonbet’s prominence was underscored in April when it briefly appeared on a government list of “systemically important companies” that would be eligible for state support during the COVID-19 crisis. It was removed from the list after prosecutors and finance ministry officials questioned its inclusion.

Following the public scandal, IStories, OCCRP’s newest Russian member center, started looking into the company. The people behind Fonbet are not widely known, but the investigation shows that several of them had suspicious connections and questionable financial dealings. It also reveals new information about the company’s opaque transfer of ownership from one set of operators to another immediately after the 2013 raid, raising questions about the police operation’s true intent.

The major findings include:

Four people associated with Fonbet sent or received large sums of money through Ukio Bankas, a now-defunct Lithuanian lender that is closely associated with the Troika Laundromat. The massive international scheme, used to launder millions through the bank, was first uncovered by OCCRP and partners in early 2019.

One of Fonbet’s founders, chess grandmaster Anatoly Machulsky, used a personal Ukio account to send nearly US$200,000 to a member of an organized criminal group led by infamous Russian mobster Alimzhan “Taiwanchik” Tokhtakhunov.

Machulsky reportedly gave up his stake in Fonbet after the police raid, though his daughter’s company continued to make millions from the company’s online business even after his death.

One of Fonbet’s new owners appears to be Alexander Burtakov, a colorful figure who has business ties with members of an elite special unit of Russia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. He is also featured in the Ukio data, which shows that he, as well as another Fonbet co-owner, received money through companies that sent hundreds of suspicious transactions through Ukio Bankas, making them a part of the Laundromat itself.

The Financial Action Task Force requires state regulators in different countries to pay special attention to the gambling industry due to the high risk that the money of dubious origin may pass through it,” said Ilya Shumanov, deputy director of Transparency International in Russia. He noted that, since the gambling business has often been used for money laundering, financial transactions through Ukio bank and Laundromat companies should be a serious cause for concern.

Reporters’ inquiries to Fonbet’s general director, its owners, and Burtakov received no response.

The Grandmaster Loses

Anatoly Machulsky, who died in London in 2017, might seem an unlikely founder of a massive bookmaking business. He was a chess prodigy in the Soviet Union, winning the country’s youth chess championship at the age of 16 in 1973, and going on to become an international grandmaster.

But his interests weren’t limited to chess. Even in the Soviet period, according to his official Russian Chess Federation biography, he was considered a “great specialist in gambling among chess players.” In the latter half of his life, Machulsky turned his hobby into a lucrative business, leaving the chess world and founding Fonbet in 1994.

But according to Ukio Bankas records, he also sent money to a member of a Russian-American criminal group that specialized in gambling. In 2010, Machulsky used a personal account at the bank to send $192,000 to a man in the United States named Anatoly Golubchik as part of an unspecified loan agreement.

Three years later, Golubchik was indicted in a U.S. district court in New York for money laundering, racketeering, extortion, and various gambling offenses. According to the indictment, he was one of three leaders of a Russian criminal group, headed by infamous underworld figure Alimzhan “Taiwanchik” Tokhtakhunov, that laundered more than $100 million in proceeds from their gambling operation into the United States. The organization operated “a high-stakes, illegal sports gambling business out of New York City that catered primarily to Russian oligarchs living in Ukraine and Russia,” according to the FBI. Golubchik was sentenced to five years in prison.

Nor was this the only time Machulsky employed Ukio’s services to handle large sums. Bank documents show that, in five transactions in 2012 and 2013, he received over $18 million from Alexey Khobot, a man who is now reportedly one of Fonbet’s major shareholders.

According to insiders, Machulsky and Khobot were in charge of Fonbet’s online betting business. The multi-million-dollar transaction is the first documentary evidence of a financial relationship between the two men.

As with many Laundromat transactions, the money moved between two Ukio accounts. The transfers are listed as payments for “loan agreements,” the nature of which is not known. Khobot did not respond to reporters’ questions sent via the general director of his Russian company.

Big Winnings

Though Machulsky lost his direct stake in Fonbet after the 2013 raid, it appears that the company continued to be a lucrative source of income for his family until 2019.

A Sudden Change

Machulsky’s ownership of Fonbet came to a sudden end after the summer 2013 raid on the company’s Moscow office.

On the surface, the police operation was straightforward: The company had run afoul of regulations that, after 2009, banned Russian companies from accepting bets online.

In response, many of them established websites in foreign jurisdictions not subject to Russian law enforcement.

“Online [bookmaking] businesses were registered in Belize, the Isle of Man, Gibraltar, or, for example, in Curaçao, the cheapest and least regulated gambling jurisdiction,” said

Paruyr Shahbazyan, the head of Bookmakers’ Rating, a website that provides analysis in the field. Such online betting platforms were popular with customers, Shahbazyan said, because the illegal transactions were not taxed.

Fonbet appeared to be using such tactics, too. Its website, fonbet.com, was operated by a Panamanian company called Fonbet Corp, and the license for the site was held by a similarly-named company in Curacao. The business was a success: Fonbet’s foreign site had over three million users the year it was raided.

But though the police operation was dramatic, outwardly there were few legal consequences for the company. Though fonbet.com was ostensibly the reason the company was raided, nothing much about its operation appeared to change afterwards. The site continued to do business as if nothing had happened, with 2.5 million people still using it the following year. Although a criminal case was opened, it resulted only in a two-year suspended jail sentence for the company’s general director at the time.

Behind the scenes, however, the incident sparked big changes. According to an acquaintance of one of Machulsky’s two former partners in Fonbet, its major owner, Vadim Sidorov, received an insistent offer to sell the company immediately after the raid, “practically in the investigators’ office.” He did so.

A man named Vladimir Bichan, who had previously led companies owned by former Internal Affairs Ministry officials, was soon appointed Fonbet’s new general director.

Fonbet’s initial new owner was Maxim Kiryukhin, a lottery operator from the southwestern Russian city of Stavropol who had run its largest franchise. But just over four years later, his stake was reduced to a minority share of just under 9 percent, while 65 percent of Fonbet’s shares were acquired by a company based in Cyprus called Birusa.

Curiously, the 650 million ruble (US$10.5 million) payment for Birusa’s acquisition was postponed until 2018. By that time, Fonbet had paid Birusa nearly the same amount in dividends, essentially resulting in an acquisition in which no money exchanged hands.

“In the eyes of tax authorities, companies that conclude such deals could be previously interconnected,” said Alexander Zakharov, a partner at Paragon Advice Group consultancy. In other words, Birusa’s acquisition of Fonbet from Kiryukhin could represent a pre-arranged swap rather than a true change of ownership.

If that is the case, the people behind Birusa could be the same ones who were behind its earlier takeover. For years, their identity was unknown, hidden behind a web of offshore firms.

But according to a report published last month by Novaya Gazeta, citing inside sources, one of its owners is Alexey Khobot, the man who had sent millions to Machulsky years earlier.

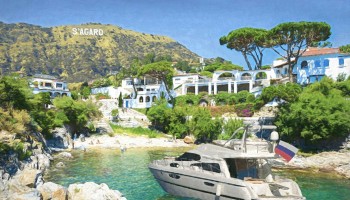

The other is reportedly a colorful figure named Alexander Burtakov. Today, Burtakov, a citizen of both Russia and Israel, is a man with wide connections and a world-spanning reach, including real estate and other companies in Malta, Monaco, and Romania. In Israel, he has a neat little house in the resort town of Herzliya, just half a kilometer from the Mediterranean Sea.

But he also had connections to the Internal Affairs Ministry. In the ’90s, he worked for Ratmir, a private security company founded by a former officer from Vityaz, a special division of the ministry. Later, Burtakov partnered with other Vityaz veterans in a company that leased out properties and sat, along with them, on the editorial board of Bratishka (“Little Brother”), a now-defunct magazine run by special units’ veterans organizations.

Though Burtakov does not appear in any public company records associated with Fonbet, he appears to be linked to the company through a valuable London property and a British company that owns its trademarks (see box).

How Burtakov is Linked to Fonbet

Alexander Burtakov does not formally appear in Fonbet’s ownership structure, but his important role in the company can be deduced from several sources.

The practice of reiderstvo — using the pressure of a criminal investigation as a pretext for snatching a company from its owner — is a well-documented phenomenon in Russia. There is no direct evidence that that’s what happened in the case of Fonbet. But the company’s sudden change of ownership after the police raid, the appointment of a general director with connections to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the revelation of a new owner with the same connections is certainly suggestive.

Laundromat Links

Prior to his involvement with Fonbet, Burtakov dealt with two companies that were part of the Laundromat.

In 2007, he received $50,000 from a Panama-registered company called Freeman Sachs Annuities Inc, which used Ukio Bankas accounts. According to the payment details, the purpose of the transaction was “for clothes,” though Burtakov is not known ever to have sold clothing.

The practice of labeling transactions with ostensible goods purchases was commonly used by Laundromat companies, which used the technique to disguise many apparently fraudulent transactions. Freeman Sachs was among the companies that used similar designations, such as “toys” or “textiles,” in thousands of other transactions.

The same year, Burtakov received $280,000 from Sherball Finance, a company registered in the British Virgin Islands that also carried out Laundromat transactions.

Sherball also appeared in a Russian criminal case in 2007. In the case, a group of fraudsters received millions of dollars for promising to settle a conflict among shareholders of Ingosstrakh, one of the country’s largest insurance companies, by leveraging connections with high-level officials. Sherball is mentioned in the verdict as a mover of some of the money, and is described as a “technical company” associated with M-Bank, a lender that lost its license in 2015 for violating banking laws.

Sergey Tetruashvili is another Fonbet owner with Laundromat connections.

Since 2003, Tetruashvili, who is registered at a German address, has co-owned Bemo Logistik, a now-dissolved Berlin-based company that supplied toners, cartridges, printer ink, household electrical equipment, and other goods to Russia and Ukraine.

Ukio Bankas documents show that in 2007 and 2008, Bemo received more than $100,000 from Adbridge Corp, a company involved in the story of Erich Rebasso, an Austrian lawyer who was murdered in Vienna in 2012 after becoming entangled in the Troika Laundromat.

Then 45, Rebasso specialized in advising Russian clients on how to do business in the West. But, as he admitted in a confessional letter to the Austrian police, he had been used to launder tens of millions of dollars. He explained that, for over a year, he had been accepting payments from Russian criminals and had sent the funds — nearly $96 million in total — to other bank accounts at their instruction. Some of the accounts Rebasso wired money to belonged to two of the Laundromat’s core offshore companies. Adbridge was one of the companies to which Rebasso transferred more than $440,000 in February 2007.

After his Russian clients began using his accounts to launder the proceeds of fraudulent investment schemes that deprived ordinary Russians of their savings, he began to receive complaints and demands for refunds. In 2012, he was kidnapped and murdered in a case that remains unsolved.