On January 9, 2014, the bulk carrier MV Kalliopi L docked at Ennore port in Chennai, the southern Indian city in Tamil Nadu, after a two-week voyage from Indonesia. It carried 69,925 metric tons of coal destined for the state’s power company.

However, the paperwork for the cargo took a more circuitous route, passing though the British Virgin Islands and Singapore.

During this journey, the price of the coal more than tripled to US$91.91 per metric ton. The quality also inexplicably changed from low-grade steam coal to the clean, high-quality version sought by power companies.

MV Kalliopi L’s profitable trip was not an isolated event. Documents obtained by OCCRP and shared with the Financial Times reveal that at least 24 other shipments that landed on the Tamil Nadu coast between January and October 2014 were originally priced as low-quality coal but ultimately sold by India’s Adani Group to the state’s power company for triple the cost.

The evidence comes from multiple sources, including invoices and banking documents from several jurisdictions, details of investigations by India’s Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI), leaked documents from a key Indonesian coal supplier for Adani, and a trove of documents obtained from the Indian state-owned power company TANGEDCO (Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation).

While not definitive, the data adds strong new evidence to over-invoicing allegations against the politically powerful Adani Group, which is perceived as close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and is India’s largest importer and private producer of coal.

The DRI, an agency under the Ministry of Finance, opened an investigation nearly a decade ago into whether Adani Group and other companies had used offshore intermediaries to inflate the price of coal supplied to utilities. But the probe was prevented from progressing in 2019 after Adani won a case in the High Court of Bombay that blocked the DRI from seeking details about shipments, including the types of invoices OCCRP has obtained, from abroad. The DRI then appealed to India’s Supreme Court, where the case has languished without progress.

Last year, opposition politicians called for a new investigation after the Financial Times reported that the Adani Group appeared to have paid over US$5 billion to middlemen for coal imported far in excess of market prices between 2021-2023.

The alleged overpricing would not only burden ordinary Indians with inflated fuel costs. Burning lower quality coal also produces more pollution, a scourge responsible for more than 1.6 million deaths in India in 2019, according to a recent study published in the Lancet.

Air pollution in Kolkata, India.

“The implications are that you have overpaid for the fuel, the second implication is that you need to burn more coal for every unit of electricity you produce, which results in more fly ash, and more pollution,” said Tim Buckley, founder and director of Australia-based Climate Energy Finance, who is a leading authority on energy financing and its implications. “More pollution and more energy poverty for the poorest people in India.”

Arappor Iyakkam, a Tamil Nadu-based NGO that has been fighting for accountability in the alleged coal scam, estimates the state’s power company TANGEDCO overpaid Rs 6,000 crore (US$720 million at today’s exchange rate) for coal from all vendors between 2012-2016, during which nearly half the value of its tenders were given to Adani, according to the organization. The NGO filed a complaint against TANGEDCO in 2018 with the state anti-corruption agency.

When asked about OCCRP’s findings, an Adani spokesperson denied the allegations as “false and baseless.”

“The suggestion that Adani Global Pte Ltd supplied to TANGEDCO inferior coal, as compared to the quality standards laid down in the tender and PO [purchase order], is incorrect,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “While it is difficult for us to comment on individual cases due to the sheer volume of data and the elapsed time, not to add the contractual and legal obligations, it is important to note that the coal supplied, irrespective of the declaration by the supplier, is tested for quality at the receiving plant.”

The Adani spokesperson rejected Arappor Iyakkam’s analysis and any responsibility for India’s air pollution or losses incurred by state power companies.

“By no stretch of imagination can Adani Global Pte Ltd, with a total supply of less than 2% of the coal burnt by TANGEDCO in the relevant period, be held responsible for either air pollution or the losses of [power distribution companies].”

TANGEDCO did not respond to questions sent by OCCRP.

One Shipment, Multiple Invoices

The documents obtained by reporters track how both the price — and in the case of the MV Kalliopi L — the quality of the coal imported by Adani increased as it moved between companies.

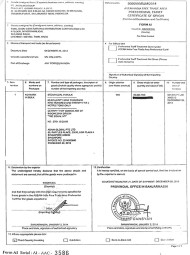

Shortly after the vessel began its journey, the provincial office in the Indonesian port city of Banjarmasin issued a certificate of origin in January 2014 identifying the Indonesia mining group Jhonlin as the consignor and TANGEDCO as the consignee of the coal onboard.

The certificate did not mention the calorific value of the coal — which measures how much energy is produced when the coal is burned and is an indication of its quality. But leaked data from Jhonlin listed the price for this shipment at US$28 per metric ton, which corresponds to the market value of the low-end coal Jhonlin was selling at the time.

Before reaching TANGEDCO, the paperwork for the shipment passed through a middleman: Supreme Union Investors Ltd, a company registered in the tax haven of the British Virgin Islands.

This company issued an invoice for the same shipment to Adani Global PTE Singapore — the group’s regional headquarters — that listed the unit price as US$33.75 per metric ton, and the quality as “below 3500” kilocalories per kilogram (kcal/kg), which is considered low grade.

But when Adani Global issued its invoice to TANGEDCO for the shipment a little over a month later, everything had changed. The unit price shot up dramatically to US$91.91 per metric ton and the coal was listed as having a calorific value of 6,000 kcal/kg, a high quality form relatively free of impurities.

Same coal, different prices

Reporters verified two dozen other coal deliveries from 2014 that follow the same pattern, with Adani earning large margins on every shipment.

According to the leaked Jhonlin data, the Indonesia miner initially supplied the shipments to Supreme Union Investors for an average price of US$28 per metric ton, a cost consistent with low-end bulk steam coal.

But records from TANGEDCO show these shipments were ultimately supplied by Adani under the contracted quality of 6,000-kcal/kg and the price of US$91 per metric ton of coal.

Though reporters were unable to obtain all original invoices, they were able to confirm the 24 shipments were the same in the export and import datasets by matching the ship, weight, and shipment dates.

Supreme Union Investors did not respond to requests to comment.

Barge loaded with piles of coal on the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan, Indonesia.

In a response to reporters, Adani’s spokesperson said the shipments were tested for quality at multiple points in the process.

“With the supplied coal having passed such an elaborate quality check process by multiple agencies at multiple points, clearly the allegation of supply of low-quality coal is not only baseless and unfair but completely absurd,” the spokesperson said.

Jhonlin did not respond to questions from OCCRP, but the miner is primarily known as a supplier of low and medium-grade steam coal, which is also supported by its own data. The dataset from Jhonlin that was leaked to OCCRP includes more than two million documents from between 2012 and 2022, including contracts, supply data, negotiations, emails, and other documents detailing the Indonesian company’s activities. Reporters could not find any example of Jhonlin providing coal with a calorific value above 4,200 kcal/kg — far below the higher quality 6,000-calorie coal which TANGEDCO ordered.

Adani’s spokesperson said that if the coal delivered had been found to be of a lower quality than what was stipulated in the contract, which allowed for a range of between 5,800 and 6,700 kcal/kg, the payment would have been reduced accordingly.

According to commercially available trade data, Financial Times journalists identified 22 of the 24 shipments and found the final payment price varied between US$87 and US$91 per metric ton, indicating that only small adjustments, if any, may have been made.

According to one Indian analyst, power generators in the country have “faced coal quality problems for decades.”

“Given the market power of coal suppliers, they often don’t have a choice but to accept grade slippage,” Rohit Chandra, assistant professor of public policy at IIT Delhi, told the Financial Times. “Third party testing has done very little to address these concerns.”

Justice Delayed

The data obtained by reporters reveals patterns similar to what the DRI described in a 2016 notice about an industry-wide case it had launched against several Adani Group companies and other firms for alleged manipulation of coal prices and calorific value.

Protesters took to the streets in Kolkata, India in 2023 following another Adani Group scandal, in which a U.S. short-seller accused the conglomerate of stock manipulation.

The agency suspected that the coal was shipped directly from Indonesian ports to India, while the accompanying import invoices took convoluted paths. They were channeled through one or more intermediaries in global hubs such as Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai, and the British Virgin Islands, before being issued to the buyer by Adani Global.

In the 2016 notice, the DRI wrote that “in a significant number of cases” two sets of test reports were discovered for consignments: “one showing lower gross calorific value (GVC) and the other higher GVC.”

But its effort to seek more information about shipments in other jurisdictions was thwarted by Adani in court.

At the request of the DRI, a Mumbai court had issued formal requests in 2017 to courts in Hong Kong, Switzerland, UAE, and Singapore, seeking help in accessing information held by Adani subsidiaries, including the details of several shipments, their associated invoices, and proof of payments.

However, Adani Group challenged the DRI’s requests to obtain its business records the following year. The Bombay High Court ruled in Adani's favor, forcing the DRI to rescind the requests.

The DRI appealed the order to India’s Supreme Court and the case has moved at a glacial pace ever since, with Adani reportedly taking three years to file a counter affidavit to the DRI’s appeal. The next hearing is scheduled for August 6.

Additional reporting by the Financial Times, Ravi Nair (OCCRP), Prajwal Bhat (OCCRP), and NBR Arcadio.