High-level employees from British American Tobacco’s U.K. headquarters oversaw a corporate espionage ring in South Africa, buying expensive surveillance equipment that was later used to illegally spy on the company’s competitors, leaked documents show.

Allegations that British American Tobacco’s (BAT) South African unit had bribed law enforcement agents to disrupt its competitors’ operations hit headlines in 2016, but no one has been convicted in relation to the claims.

Now, analysis of confidential documents seen by OCCRP and its partners reveal in fresh detail how the operation worked, including a previously unknown level of involvement from the tobacco giant’s London headquarters.

The material, collated from industry and government sources, shows BAT officials from London received regular reports on the spy ring, participated in planning, and spent tens of thousands of dollars on equipment that was used for illegal surveillance.

In total, BAT signed off on $42.6 million for surveillance between 2012 and 2016, the documents show.

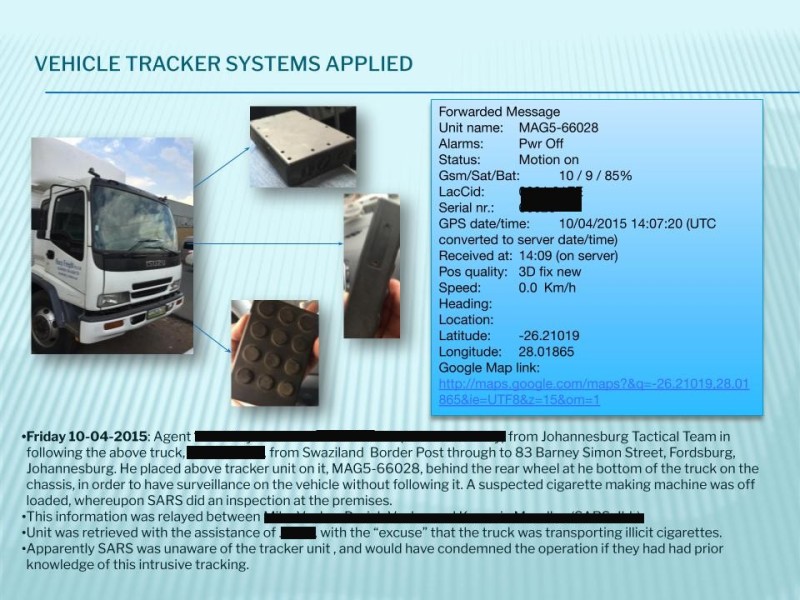

One of the companies targeted, Carnilinx, filed civil charges against the tobacco giant in 2014 after finding a tracking device on one of its vehicles that it believed could be traced back to a security firm contracted by BAT. The civil case was dismissed by a South African court on a technicality, with the judge noting that the outcome shouldn’t be seen as a vindication of the tobacco giant. A criminal case against BAT, which was filed later, is still making its way through the courts.

The scandal left in its wake a revenue agency shaken to its core, and caused a rift of distrust between law enforcement agencies in South Africa.

“Authorities in South Africa have known of BAT's corporate espionage ring for years. The evidence has always been there, yet nothing has come of it,” said Johann van Loggerenberg, a former executive with the South African Revenue Service who was also a witness in the case.

“There need to be penalties for this kind of behavior or corruption will only continue to flourish.”

BAT disputed the fresh revelations, saying its programs in South Africa were intended to fight cigarette smuggling by providing support to law enforcement, including “intelligence on suspected illicit operators.”

“We emphatically reject the mischaracterisation of our conduct by some media outlets,” the company said in a statement to OCCRP’s partners, BBC Panorama, Bath University’s Tobacco Control Research Group, and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. BAT U.K. declined to respond to OCCRP’s own questions.

BAT has faced similar allegations elsewhere in Africa. The U.K.’s Serious Fraud Office dropped a related investigation earlier this year that focused on alleged corruption in BAT’s East African business, saying its findings “did not meet the evidential test for prosecution,” which requires cases to be “in the public interest” as well as provable in court.

The tobacco company referenced the investigation in its statement to OCCRP’s partners.

“In 2016 BAT made public that it was investigating allegations of misconduct and was liaising with the U.K. Serious Fraud Office (SFO). BAT fully cooperated with the SFO’s subsequent investigation, which included allegations relating to South Africa,” the company wrote.

Desperate Times

Big Tobacco has a sordid history, with the world’s top cigarette makers found guilty of smuggling their own products in various countries, and covering up the link between cigarettes and cancer.

But the BAT spy ring in South Africa, which documents indicate ramped up its operations between 2012 and 2016, showed just how far the tobacco major would go to retain its market dominance.

As the 21st century began, BAT brands accounted for up to 95 percent of South Africa’s national market. But the number of smokers was shrinking, with the share of the population falling from 33 percent in 1993 to 20 percent in 2017.

At the same time, smaller manufacturers were undermining BAT South Africa’s dominant position, selling their cigarettes for half the price of the established brands, while a booming illicit trade in cigarettes was further eroding the tobacco major’s share.

So BAT, the maker of Dunhill and Lucky Strike, spent millions of dollars setting up a spy network of agents embedded in its competitors’ businesses.

The foot soldiers who formed the nucleus for the offensive came from Forensic Security Services (FSS), a private South African security firm that BAT employed at an estimated cost of 600 million South African rands (US$42.6 million) paid out over four years. Through FSS, BAT co-opted law enforcement agencies and employed state intelligence and law enforcement officers who impounded competitors’ products and even used traffic cameras to spy on rivals.

“[T]he purpose of my employment was for BATSA [BAT South Africa] to deploy my investigative skill together with backup from corrupt SAPS (police) and SARS (tax revenue) officials in order to disrupt the business of BATSA’s competitors,” said Francois van der Westhuizen, a former FSS operative, in an affidavit filed in South Africa’s Western Cape High Court as part of the Carnilinx case.

He added that BAT South Africa managed and approved operations, encouraging illegal means to sabotage competitors, and directly paid a network of informants, including police and tax officials.

One internal FSS presentation was emblazoned with images of army dog tags and a Colt pistol, and included the battle cry: “We will disrupt the enemy. We will destroy their Warehouses. We will blow up their supply lines.”

Correspondence, affidavits, and other documents show three former British intelligence officers, who answered directly to senior BAT employees, travelled regularly between London and South Africa, conducting training of FSS operatives, signing off on payments, recruiting and running their own agents, and overseeing surveillance operations.

“BATSA management had me trained in industrial espionage by ex-UK military intelligence agents,” van der Westhuizen told South African media.

“We were trained in vehicle tracking systems, counter surveillance and information peddling. We were tasked to spy on local cigarette manufacturers.”

Lawyers for all three of the former British intelligence officers denied they had ever broken the law and said they adhered to BAT’s policies.

The Network

At BAT’s bidding, FSS set up a network of informants and undercover agents to feed them inside information on the competition.

OCCRP has obtained documents containing details on more than 200 such agents, including the dates when they were active and the names of their handlers. Some were paid monthly, while others were occasional “consultants.”

Repeated attempts to obtain comment from FSS for this story proved unsuccessful.

FSS’s tactics included bribing law enforcement officials to raid BAT’s competitors’ premises, “under the guise of conducting raids, to obtain copies of invoices, production sheets and documents” that would be turned over to BAT South Africa. FSS agents also sabotaged machinery, conducted surveillance, intercepted phone conversations, and tracked the vehicles of BAT’s competitors.

These operations were repeatedly reported back to BAT division heads based in London.

The leaked documents include an outline for an operation aiming to “cause a substantial rift between the distributors ... through means of jealousy or false reports.” Minutes from a meeting between FSS and BAT South Africa record the question: “Can we utilise current network to ‘set up’ any one?”

The documents also show FSS collected photos of competitors’ invoices and delivery notes, and of the machinery in their factories.

BAT’s agents included Belinda Walter, an attorney acting for Carnilinx and the founding chairperson of the Fair-Trade Independent Tobacco Association, an industry body representing smaller independent manufacturers. Walter later publicly admitted that she had spied on her own clients for both BAT and the State Security Agency, while also infiltrating South Africa’s revenue agency.

In a Blackberry messenger group called “Evil Inc” created by Walter, her clients at Carnilinx and other independent manufacturers talked strategy. At one point they discussed the idea of spreading misinformation or "exterminating" another manufacturer they disliked. What they didn't know was that Walter was feeding information from this chat group directly to BAT.

FSS’s agents on retainer included policemen, municipal law enforcement officers, and officials from the tax revenue services. According to van der Westhuizen’s affidavit, these law enforcement officers were typically paid up to R5,000 a month (about $355).

Among other things, this money bought BAT the opportunity to have its competitors’ tobacco shipments stopped and held up by compliant law enforcement officials, van der Westhuizen explained. Often the tobacco would be held for a few days — just long enough for it to go moldy.

“[T]he primary objective was to have the tobacco seized, taken into police custody for several days, and thereafter for it to be released because there was generally not a good ground for having seized it in the first place,” van der Westhuizen wrote.

According to him, FSS was even granted access to a bank of 240 police cameras across Johannesburg, which allowed agents to monitor Carnilinx’s vehicles around the clock. “A special camera, camera number 5, was strategically positioned so as to allow FSS to view Carnilinx’s premises,” he claimed, attaching to the affidavit several photographs of private property he said he obtained using this camera.

OCCRP is in possession of invoices for cash rewards to informants individually signed off by BAT’s head of anti-illicit trade for Africa, their local head of anti-illicit trade in South Africa, and BAT’s country manager.

BAT apparently paid some of their sources monthly retainers of up to 40,000 South African rand (almost $2,800). Some agents were paid out of BAT offices in London using prepaid Travelex cards, which allowed them to anonymously withdraw cash anywhere in the world, making the movement of funds virtually impossible to trace.

Later, Walter said she became concerned this constituted money laundering.

“The anti-illicit trade activities that took place in South Africa more than half a decade ago were aimed at lawfully exposing the criminal trade in tobacco products,” BAT said in its response to questions.

High-Tech Surveillance

The leaked documents show FSS invested heavily in surveillance equipment to track what BAT’s competitors were doing, from their movements to their correspondence.

In July 2013, FSS bought a Desert Wolf surveillance vehicle, touted on the company’s website as an “ultra capable roaming surveillance system,” equipped with a tactical command and control center. BATSA was copied on emails regarding outstanding payments, indicating that the vehicle was intended for the tobacco company’s use.

One email from the managing director of Desert Wolf, who wrote in Afrikaans, noted: “During my last contact with FSS… everybody at FSS and your client were VERY satisfied with the whole system.”

Members of BAT's spy ring also targeted the phones of Carnilinx employees and directors, intercepting their phone calls, installing secret software on their cell phones, and using hidden cameras to track their movements, van der Westhuizen claimed.

The leaked records show FSS billed BAT for more than $150,000 on operations that involved probers, cell phone surveillance and disbursement to agents. The company made use of highly specialized technical equipment including drones, cameras, and a “Black Widow” solar-powered surveillance vehicle capable of wide-ranging infiltration.

FSS also prepared a detailed guide on how to access the information on people’s cell phones using spyware, including browser histories and WhatsApp messages, as well as how to track a phone’s location and activate its microphone remotely to listen in on conversations.

An FSS employee explained in a funding request to BAT: “To get the software installed on a phone will require more than your average operation and some clever thinking from our part, but I am confident in our ability to rise to the occasion.”

‘Unlawful Relationship’

The documents seen by OCCRP and its partners, as well as the information disclosed by former agents like Walter and Van der Westhuizen, make it clear that FSS and BAT knew their agents were involved in illegal activities.

One FSS document instructs agents to avoid certain words that could raise red flags: “Always refer to insource/outsource and not electronic monitoring, plugging, advanced monitoring or beacon on. Always refer to Investigation done, and not observation, surveillance or monitoring.”

In an email exchange between senior FSS managers, they discuss what to do after Carnilinx discovered an illegal tracking device on one of its trucks: “[P]lease retrieve unit and DO NOT report any further on this activity […] I repeat do not repeat these activities [...] because if someone sees us working on it, we are…”

Walter, the attorney for Carnilinx who also spied for BAT, said her BAT HQ handlers seemed well aware that their activities were criminal in nature. In her 2015 affidavit she says she had told BAT U.K. she wanted out.

“BAT UK’s and Evans’ responses to my requests for clarity and information … made it abundantly clear to me that the relationship we shared may well fall within the ambit of a corrupt or unlawful relationship,” she testified.

Carnilinx took legal measures to fight back against BAT. The South African firm lodged corruption charges against BAT’s directors, accusing them of corporate espionage, and accusing various government entities of giving preferential treatment to the tobacco giant.

But no charges stuck to BAT, despite revelations about the company’s espionage activities and allegations of corruption that leaked out over years.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misidentified the brand of gun pictured on an internal FSS presentation. It was a Colt.