As the sun sinks in Juba, South Sudan’s capital, a 29-year-old policeman has just finished his shift. Out of view of a busy street, he changes into civilian clothes before class at a nearby university.

Abraham Malual Akol Dhel, a father of two, says he’s hoping to retrain into another career because the government hasn’t paid his salary in months. The university, aware of his financial situation, enrolled him in an environmental studies program without an upfront payment, he says.

But for now, he’s the only breadwinner for an extended family of 10 and he must wait for his wages. Sometimes his children go days without eating.

“I’m suffering, but what can I do?” he asks, steadying his officer’s cap. “Who will help me?”

South Sudan hasn’t paid its government employees, including doctors, teachers and lawmakers, for several months. It says it simply can’t afford to.

The East African country has been ravaged by decades of conflict, and most recently, a brutal six-year civil war that has claimed the lives of at least 383,000 people. The UN says more than 4 million – about one third of the population – are displaced from their homes.

The conflict, and low oil prices, have battered the economy, which is one of the world’s most oil-dependent. South Sudan’s gross domestic product has plummeted from US$13 billion at the start of the civil war to just $3 billion as of 2016.

Even a fragile peace deal, signed last year after several previous agreements had failed, could be jeopardized by a lack of funding to implement its ambitious provisions, including the reintegration of opposition fighters into the armed forces, the government says.

Under the terms of the deal, the government and main opposition parties are meant to form a transitional government — but its creation was postponed for the second time just weeks ago.

When it is formed, that new government will have to service a massive debt, much of which is secured against the country’s oil reserves. Experts worry that ongoing peace-building efforts will be undermined by corruption and financial mismanagement.

The agreement “takes a big tent approach, trying to bring everybody in, but that requires money which isn’t there,” says one prominent South Sudanese researcher, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals from the government.

Yet Juba is spending well beyond its means. Earlier this year, the country's parliament recommended cutting 10 percent of its meager peace fund to help pay for a new presidential jet and a $50,000 healthcare allowance for each lawmaker. Significant funds are also flowing to the military, which the UN has accused of a host of human rights abuses, including widespread rape, arbitrary detention, and enforced disappearances.

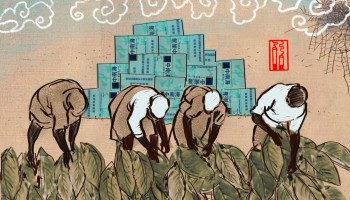

South Sudan’s dire financial situation appears to be, at least in part, the result of efforts by the office of President Salva Kiir to steer public finances and future oil revenue to three businessmen connected to his office.

According to contracts, bank records, and government correspondence obtained by OCCRP, the government awarded procurement contracts worth $1.4 billion to supply food and vehicles to the government and the national army between 2016 and 2018. Just four companies received these contracts — all of which can be traced to the three businessmen with close ties to the Office of the President.

Bribery, kickbacks, and procurement fraud

Two of the businessmen involved in the contracts, Ashraf Seed Ahmed Al-Cardinal and Kur Ajing Ater, were sanctioned by the United States on Oct. 11 for their involvement in “bribery, kickbacks and procurement fraud with senior government officials,” according to a U.S. Treasury statement.

The contracts were intended to supply goods and services to the national army and state security forces, among other agencies. They include:

$578 million to supply food to the government, awarded in 2018;

$539 million to supply food to the army, awarded in 2016;

$94 million to supply 1,000 vehicles to security forces, instructed by the office of the president to be awarded in 2018;

Two contracts worth a combined $90 million to supply food to the government, instructed by the office of the president to be awarded in 2018;

$81 million to supply vehicles, motor boats, and communications equipment to security forces, awarded in 2018.

These amounts are so vast that it would have been impossible for the government to pay them in full. In his July 2018 budget speech, finance minister Salvatore Garang Mabiordit estimated that only about $520 million dollars in revenue was available to the government that year.

The contracts also appear to have violated several of South Sudan’s procurement laws. One was awarded without a competitive bid, undermining the government’s ability to secure the best possible price. Several significantly exceeded budgeted spending limits. The value of one of the smaller contracts exceeded South Sudan’s entire military budget for goods and services for that year by a factor of ten.

Financing for others was secured through pre-sales of oil, a widely-criticized practice that saddled the struggling country with massive debts. These arrangements were also made without the required approval and oversight.

In several cases, President Kiir personally intervened to facilitate the awarding of these contracts to specific companies and businessmen, even when oversight institutions or other senior officials raised concerns.

Mabiordit, the finance minister, has been candid about the reasons for the government’s overspending. “We have weak procurement practices,” he wrote in a prepared parliamentary speech.”Expenditures are not properly prioritized.”

But the president and his influential associates proved too powerful.

“How the core group around the presidency operates is murky and subject to much intrigue,” says Alan Boswell, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group, a conflict prevention NGO. “The number of winners within the elite has dwindled to a small group of people – mostly from communities near the president’s home area – who are receiving most of the benefits.”

Detailed requests for comment sent to the president’s office, the defense ministry, and South Sudan’s Director General of Information, Mustafa Biong Majak Koul, went unanswered.

However, in a recent public response to a UN monitoring group report, the government acknowledged that it had made payments to Kur Ajing Ater and his company, Lou for Trading and Investment Company Ltd., “to meet contractual obligations.”

Defense Disbursements

It is unknown how much of the $1.4 billion total was actually paid or whether any of the deliveries were made in return.

A recent government report documents massive defense spending that overlaps with the time period when several of the contracts were awarded. Just nine months into the 2018/19 financial year, the budget for the country’s armed forces had already been overspent by around 250 percent. The report also identifies the Ministry of Defense, which negotiated most of the contracts, as responsible for the vast majority of the excess spending, attributing most of the unbudgeted expenses to the procurement of goods and services.

There is also evidence that at least some of the contracts were partially honored, netting substantial payments for the businessmen connected to the president.

Central bank withdrawal slips obtained by OCCRP show that Kur Ajing Ater, the owner of one of the companies that won at least two contracts, received at least $23 million of public funds, mostly in dollars withdrawn as cash, between June and October 2018. Some of the slips note “vehicles” and “food for army” as reasons for the withdrawals, indicating that these were probably related to the military contracts.

In a separate document from November 2018, the finance ministry authorized another transfer of $38 million to Ater, specifying it as a payment for a contract to supply food to the army. Ater received his contract to do so in 2016, with government payments spread across three years. Ater did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The subsequent contracts sought to procure still more food and vehicles for South Sudan’s government. They can be traced to two businessmen, Ashraf Seed Ahmed Al-Cardinal and Kiir Gai Thiep, both of whom have close links to the president as well as commercial ties to each other.

The Arms Embargo Race

The clearest violation of South Sudan’s procurement laws occurred in mid-2018, when defense ministry officials tried to resurrect a previously thwarted contract to supply vehicles and communications equipment to the military as the prospect of an international arms embargo loomed.

Correspondence and other documents related to the contracts offer a rare insight into South Sudan’s patronage politics and the influence of the defense ministry over the country’s oversight bodies.

The ministry first awarded the $81 million contract to Ater’s Lou Trading and Investment Co. in 2017, but the finance ministry refused to approve it. According to correspondence obtained by OCCRP, the ministry cited the lack of a formal contract and the fact that the requested amount was “much higher” than the approved budget.

Undeterred, the defense ministry spotted a second opportunity to get the contract approved the following year — with the added pressure of time.

The spring of 2018 had seen heavy fighting between the national army and opposition groups in South Sudan’s volatile Unity State, with both sides committing widespread sexual violence and other “gross violations and abuses of international human rights,” according to the local UN mission.

The UN Security Council, which had previously imposed sanctions on individual perpetrators, was divided on the best way to stop the fighting. As an annual meeting to discuss the sanctions neared, the U.S. delegation pressed for an arms embargo that would staunch the flow of weapons into South Sudan. Ethiopia, which was hosting peace talks, pushed for additional time to strike a peace deal.

In a May 30 vote, the council renewed existing sanctions, but stopped short of imposing an arms embargo. Another vote was to be held in 45 days. If the country didn’t reach a “viable” agreement, another opportunity to impose an embargo remained.

That prospect sent officials in Juba scrambling to revive the $81 million contract for vehicles and communications equipment.

Two days before the UN vote, the defense ministry invited Ater’s Lou Trading to resubmit its previous bid, according to contracts and correspondence obtained by OCCRP. Ater responded by crossing out the contract’s old date of Feb. 2, 2017 and writing in May 29, 2018. It was the only bid.

The defense ministry established a negotiation committee on the same day that Ater submitted his bid. The committee immediately announced that it had settled on a price that exactly matched Ater’s offer.

As before, finance ministry officials raised several objections to the deal, including the lack of adherence to procurement procedures.

Additionally, there was “no urgency to justify the single source procedure,” Majok Dau Kout, the head of the ministry’s legal administration, wrote in an internal legal opinion that June. He also noted that the defense ministry’s designated budget couldn’t cover the cost and that it had no plan to train soldiers to use the new equipment.

He recommended the contract be denied.

In fact, South Sudan’s entire approved budget for military goods and services that year was 1.4 billion SSP. This single contract — worth around 12.5 billion SSP at the budgeted exchange rate — would therefore exceed approved military spending by a factor of ten, surpassing the government’s entire 9.3 billion SSP budget for goods and services.

Nevertheless, for reasons that are not clear, on Aug. 24, the finance ministry approved the contract. By then, Ater had already withdrawn more than $10 million from the Central Bank.

OCCRP was not able to determine the extent to which the contract was fulfilled. Any vehicles or equipment supplied to the army by Lou Trading after July 13 would have been banned, as the UN Security Council finally imposed an arms embargo on that date.

Food For The Army

President Kiir’s trademark cowboy hat shielded him from the scorching sun as he watched a short military parade on Jan. 24, 2019. Afterward, on the parade ground, he awarded medals to several senior officers in recognition of their long-standing service.

One of the attendees, Lt. Gen. Gabriel Jok Riak, had recently been promoted to the Army’s Chief of Staff, despite having been sanctioned by the UN for “extending the conflict” and repeatedly violating ceasefire agreements.

“When I went to the parade, I saw the health of the soldiers is really too bad,” Kiir said in an address. “If the health of the soldier is not good it is because you are not feeding them.”

Kiir then reportedly turned to the officers, their new medals gleaming in the afternoon sun. “Starting from General Jok and going down to all commanders of the units, I’m not happy with all of you, and I have to say it,” he said. “We do bring food, but when they get to your stores, you take it to the market.”

The president was accusing his most senior military officers of stealing food intended for their soldiers and selling it for personal profit.

In fact, he might as well have said the same about himself.

The most valuable contracts analyzed by OCCRP were related to food supplies for the army and government. These contracts, too, violated procurement laws and vastly exceeded budgeted amounts. In several cases, even after oversight institutions raised concerns, President Kiir personally intervened in favor of specific companies. Some of these — which were awarded contracts totalling more than $1.1 billion — appear to be linked to the Office of the President.

“The legacy of food supply is deeply entrenched in corruption in South Sudan,” says Stella Cooper, a senior analyst at C4ADS, an independent Washington-based think tank.

Pounds, Dollars, and Exchange Rates

In October 2015, the government awarded a $539 million contract to Lou Trading to supply more than 45,000 tons of basic food to the defense ministry.

But just two months later, the situation changed drastically. In December, the government abandoned its fixed exchange rate of 3.16 SSP to the dollar. (The change was dramatic. For example, by the 2016/2017 financial year, the government was using an exchange rate of 70 SSP to the dollar.)

As the South Sudanese pound rapidly depreciated, and the cost of dollars rose, so too did the cost of the food to be imported under the contract — meaning that Lou Trading would lose money under the terms of its recently-signed deal.

Given the country's shortage of foreign currency, even contracts denominated in dollars would likely have to be paid at least partially in South Sudanese pounds. This made the new exchange rate an acute problem.

On March 9, 2016, Defense Minister Kuol Manyang Juuk gave a “green light” to revise the agreement using new prices based on the current rate.

That same month, in a letter to Juuk, the president’s office made clear Kiir’s interest in ensuring Lou Trading’s contract would move forward unimpeded. The letter included a document confirming that the company had been awarded a contract to supply food to the army. “H.E. the President of the Republic has directed that this document is for your necessary action,” the letter read.

That November, the finance ministry approved the revised contract — which now became even more colossally expensive.

An official procurement form filed by the defense ministry spreads the cost of the revised contract over three years, with payments to be made in installments of $180 million each year.

At the new exchange rate, each of these installments would have been equivalent to about 12.6 billion SSP, making even one of the payments considerably higher than the entire security sector’s budget for the year. (The 2016/2017 budget was 11 billion SSP).

It is ultimately unclear whether any payments or deliveries relating to this contract were made. But while Kur Ajing Ater’s cash withdrawals and transfers from the central bank in 2018 provide minimal information about their purpose, three of them specify that they are payments for the supply of food to the South Sudanese army.

A legal document issued in October 2018 also describes an active contract for Lou Trading to supply food to the South Sudanese army during the 2018/19 financial year. This suggests the original contract may have remained in effect, or that Kur Ajing Ater and his company may have been awarded another. Lou Trading did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a separate document dated Nov. 29, 2018, the finance ministry authorized a payment of $38 million to Ater “to meet the cost of food items supplied” to the army. At the time, this amount was equivalent to 5.9 billion SSP – more than twice the 2.2 billion the army and security services had budgeted for goods and services.

According to the document, this sum was to be taken from an oil prepayment the government had recently received from an international commodities trader.

Such arrangements allow the government to access quick cash by receiving payments for oil deliveries that have not yet been made. But they come at a significant cost.

Mortgaging the Future

South Sudan’s government is the most oil-dependent in the world. In its budget for the current financial year, oil income accounts for about 83 percent of estimated government revenues. It also guarantees most of the government’s borrowing given its limited access to international financial markets, experts say.

The country’s protracted conflict has made it difficult to boost oil production, particularly in the oil-rich Unity State, where output has only partially recovered after heavy fighting led to its suspension in 2013.

Selling future oil production is the government’s way of generating revenue despite these obstacles. Under such arrangements, a small number of commodity traders pay the government for oil it expects to receive at a future date. In return, since the payment is effectively a loan, the company receives a discount on the oil and charges interest on the prepayment amount.

“Commodity traders are not just trading. They are lending, and lending on a vast scale,” says Natasha White, an oil researcher at Global Witness. “They are increasingly assuming the role of banks in a largely unregulated market, lending to governments which may have limited access to more traditional financial institutions.”

But the practice has implications for transparency.

“These are by their very nature risky deals,” White says. “It’s cyclical. The governments that make use of this form of borrowing do so because they are strapped for cash … But as a consequence, large amounts of cash are injected into economies where poor revenue management makes them very difficult to monitor.”

Oil for Food

On Feb. 20, 2017, President Kiir hosted a meeting at his Juba presidential compound, which still bore the scars of the fighting that had erupted in the capital the previous summer.

Among the attendees was Mabiordit, the finance minister, and Thiep, one of the businessmen linked to the president.

Thiep comes from Gogrial, a state in northern South Sudan that is also the home of President Kiir. He owns several South Sudanese companies.

He also owns Kiir for Services and Construction Co. — which, during the meeting, was promised a massive contract to supply food to the military at the president’s personal behest. A letter confirming the offer was sent by the president’s office two days later. “His Excellency the President has reiterated this process should be given due attention as soon as possible so that the looming hunger in the country could be mitigated,” the letter reads.

According to the letter, the president issued “a verbal directive” that the company would supply food to the government in exchange for future deliveries of crude oil.

The contract for the deal, obtained by OCCRP, would ultimately be worth $578 million, to be paid for by the allocation of fifteen cargoes of oil. The government was again seeking to finance a vast procurement deal, awarded in contravention of normal procedures, by mortgaging future oil production.

By September 2017, Kiir For Services and Construction had accepted the terms of the agreement and developed a memorandum of understanding with the trade ministry.

On Oct. 5, however, the finance ministry intervened, noting that there was not enough available oil to make such a commitment. Instead, the ministry proposed a rolling allocation of one oil cargo at a time – equivalent to 600,000 barrels – against the company’s food deliveries.

A few days later, on Oct. 9, the Office of the President again wrote to the finance minister. The letter repeated the president’s directive: “I am writing on urgent directives of His Excellency the President instructing your esteemed office to allocate crude oil Cargos worth USD 578 million to Kiir Service Company [sic] as payment guarantees for food imports in the country,” the letter reads.

Almost a year later, on Aug. 8, 2018, the oil allocation was made. Later that same month, the contract was signed with finance ministry approval.

While the finance ministry recorded significant unbudgeted spending on military goods and contracts during the 2018/19 financial year, it has not been possible to confirm whether payments or deliveries have been made against this particular contract.

Familiar Faces

Far from moderating its spending to fund the peace process, the government appears to have identified it as an opportunity for more.

Along with the peace agreement came extra funds to pay for its implementation, including many aimed at reforming the security sector. These funds were administered by a National Pre-Transitional Committee (NPTC), tasked with preparing the parties for the formation of a new power-sharing government.

On Nov. 5, 2018, just a few months after the peace agreement was signed, the chairperson of the NPTC, who also works in the Office of the President, asked the committee’s secretary to prepare a contract to award Al Cardinal Investment Co. Ltd. a $47.7 million contract to supply food to Juba and the Bahr el Gazal region. A separate contract, ordered on the same day, awards his company an additional $42.5 million to supply 50,000 tons of sorghum, also to Juba and Bahr el Gazal.

The company is owned by Al-Cardinal, a Sudanese businessman recently sanctioned by the U.S. government. He has been routinely implicated in procurement controversies, including the supply of tractors, vehicles, and grain to the government at inflated prices.

Also on Nov. 5, the same NPTC officials ordered the drafting of a contract following an agreement with Green for Logistics, a company based in the United Arab Emirates, to supply 1,000 vehicles to Juba and Bahr el Gazal for $94.5 million. UAE company ownership records show that Green for Logistics is part-owned by Al-Cardinal. This same company had previously supplied South Sudan’s army with amphibious military vehicles. Green for Logistics did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

According to documents obtained by OCCRP, Al Cardinal has also enjoyed a close business relationship with Thiep. The two businessmen and procurement moguls have jointly owned at least three South Sudanese companies, Al Cardinal Technologies Company Ltd., Junib Technologies Company Ltd., and Southern Al Cardinal for Building and Construction Ltd. Multiple phone calls to Thiep and Kiir For Services and Construction Co. went unanswered. OCCRP was unable to reach Al-Cardinal or his company, Al Cardinal Investment.

Counting the Cost

The same secrecy and informality that have shielded the procurement process from proper scrutiny in the past has made it almost impossible to monitor current contracts, experts say.

“There is a staggering lack of transparency around government contracts in South Sudan, including basic information about quantities allocated and the companies receiving those contracts,” says Cooper of the Center for Advanced Defense Studies.

The South Sudanese people have paid the greatest price for conflict and economic mismanagement. The debt accumulated as a consequence of unaccountable government spending detailed in these contracts will trouble South Sudan for some time.

“The government has long been an extractive enterprise in South Sudan,” says a prominent South Sudanese researcher, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal from the government. “A basic understanding of the relationship between the government and the people is lacking. The role of government is not to sit on your neck; it is to bring some kind of public good and service to the people.”

Seated in a dimly lit room in a school in Juba, a 38-year-old teacher, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal from his employer, hangs his head. In September he received his salary, which was meant for May. Yet he is still owed months of back pay and the money he received isn’t enough to feed his family.

“You feel depressed because when we got our independence the ambition we had, to have a prosperous South Sudan we’d be living happily,” he said.

“But unfortunately, our leaders chose to fight among themselves and now the whole [country] is paying.”

Editor’s Note: Michael Gibb is the former coordinator and natural resources expert of the UN Panel of Experts on South Sudan, an independent expert body that advises the UN Security Council. None of his reporting in this article overlapped with his time in that role. All the documents that are cited in this article were obtained independently by OCCRP.

Additional reporting by Sam Mednick and Khadija Sharife.