The Democratic Republic of the Congo -- a resource-rich country in central Africa that is almost 7 times the size of Germany -- is also one of the world’s poorest. Nearly 8 million people, or about 10 percent of the country’s population, “face acute hunger,” according to a recent report by the United Nations food agencies -- and it’s getting worse. Almost half of Congolese children under five are malnourished.

So it might seem like an encouraging sign that a tax-exempt company that promised to supply inexpensive imported food for the country’s citizens received millions of dollars from the government in 2013. But something was not right.

First, the transactions -- US$ 43 million in total -- were deposited to the company’s accounts from the DRC’s central bank. As a rule, central banks don’t make payments to private companies. Their role is to regulate the banking industry, control the country’s monetary policy and to be the sole provider and printer of notes and coins in circulation. That makes these transactions illegal (and likely means that the Congo’s cash-strapped budget was partly footing the bill).

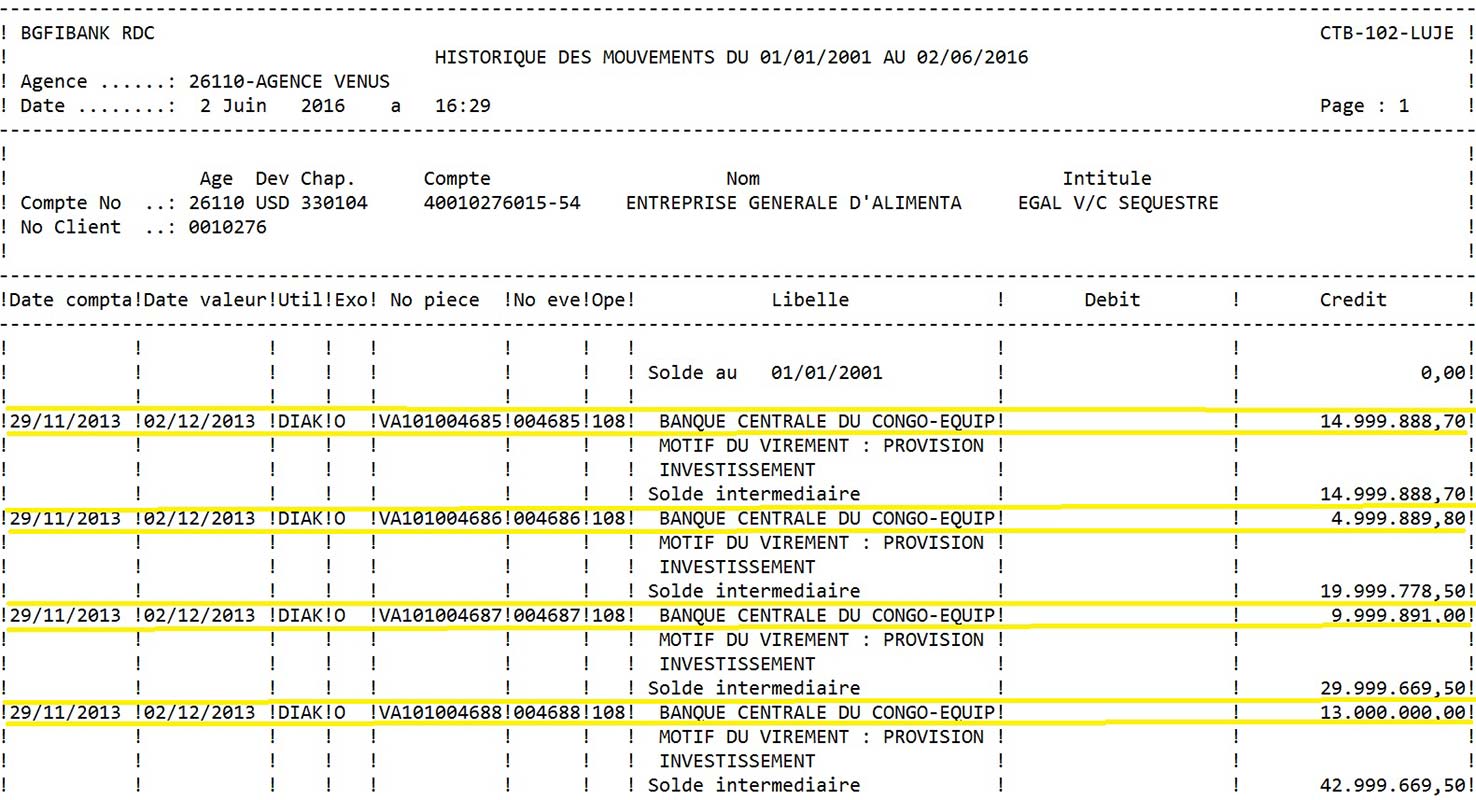

In a BGFI transaction record, four payments from the Central bank to EGAL are highlighted in yellow (click to enlarge). Then, instead of solely purchasing food, the millions passed through the company only to end up in the pockets of a small group of President Joseph Kabila’s associates.

In a BGFI transaction record, four payments from the Central bank to EGAL are highlighted in yellow (click to enlarge). Then, instead of solely purchasing food, the millions passed through the company only to end up in the pockets of a small group of President Joseph Kabila’s associates.

These revelations are possible thanks to banking records and other information provided to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and Le Monde by the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers in Africa, an organization that protects whistleblowers from prosecution. (Khadija Sharife, an author of this story, is one of the organization’s directors.)

The records trace the flow of money from the Central Bank of Congo (CBC) through the food company, Entreprise Générale d'Alimentation et de Logistique (EGAL), and on to other firms run by two of EGAL’s board members, Alain Wan and Marc Piedboeuf. The two men are known Kabila associates whose multiple companies have received lucrative government contracts in everything from construction to eco-tourism.

The leaked records were provided by Jean-Jacques Lumumba, a former banker at a Congolese branch of a major Central African bank called BGFIBank. The branch, where EGAL held one of the accounts into which funds were deposited, is run by President Kabila’s adopted brother, Francis Selemani Mtwale, and co-owned by his sister, Gloria Mteyu.

A Company To Feed the Poor and Hungry

The alleged raison d’être of the tax-exempt EGAL -- to sell competitively priced food, especially fish, to the DRC’s hungry people -- sounds altruistic. But in reality, importing fish was just one of its many activities.

Its success appears to have depended on its co-founders’ connections to President Kabila. In an interview with OCCRP and Le Monde, Wan explained how he and his partner Piedboeuf “gathered all [their] assets” and pitched their vision to the Kabila regime.

Their proposal seems to have met with approval. Their new company, EGAL, was officially incorporated on October 12, 2013 with $350,000 in capital -- and valuable tax-exempt status.

But the leaked banking records show that, in fact, EGAL had been financially active three months earlier. By the end of the year, in four tranches, it had received $43 million from the CBC in spite of laws and regulations. Article 6 of the legislation that governs the Central Bank, does not allow disbursements to private companies regardless of the reason.

Albert Yuma Mulimbi, a member of President Kabila’s inner circle, a CBC board member, and chair of its audit committee, also sits on the board of EGAL. In an interview with OCCRP reporters, he defended the company, claiming that it was “the largest importer of fish for the Congolese consumer,” and that prices had fallen by an average of 25 percent over an unspecified period. (OCCRP could not corroborate these figures independently.)

Egal’s draft audit shows Yuma and Texico, a company he told OCCRP that he chairs, hold part of EGAL’s share capital.

Yuma denied that the CBC had sent any funds to EGAL at all. To do so in the DRC would be illegal, “like everywhere else in the world, as far as I know,” he said. He called the allegations “simply false.”

The leaked bank transfer records say otherwise.

Furthermore, the records show few signs of normal business activity surrounding the received funds, such as incoming and outgoing transactions that would indicate income, wages, rents, or other payments. OCCRP did not have access to other bank accounts that may have belonged to EGAL.

A shady loan

Lumumba, the whistleblower who leaked the documents, told OCCRP the CBC payments served two purposes for the enterprising businessmen. The first was get the Central Bank’s money funneled through EGAL to various private companies with which the men are linked.

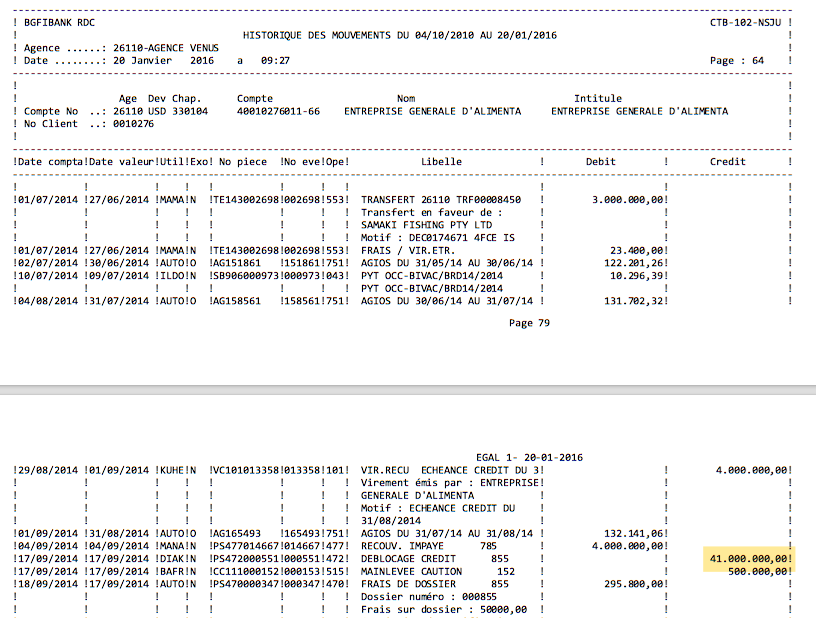

The second was access to a $41 million loan from BGFI, which they were able to obtain by using the illegally received funds as collateral. This transaction also appears in the records. According to Lumumba, the loan was more of a “grant” since, as of the date he left the bank, no significant repayment had been made.

An excerpt from a transaction record shows a $41 million credit to EGAL’s bank account at BGFI. (Click to enlarge)BGFI’s Congolese branch -- run and co-owned by Kabila’s family -- has an agreement with Western Union which enables it to carry out financial services outside of the DRC.

An excerpt from a transaction record shows a $41 million credit to EGAL’s bank account at BGFI. (Click to enlarge)BGFI’s Congolese branch -- run and co-owned by Kabila’s family -- has an agreement with Western Union which enables it to carry out financial services outside of the DRC.

Asked by OCCRP about whether it had thoroughly checked out its Congolese partner, Western Union confirmed that it had an agreement with BGFI Bank in Gabon and 51 locations in the DRC. “Our processes include due diligence and ongoing reviews of [an agent’s] sub-agents, individuals or entities with a controlling interest,” said Pia De Lima, Vice President of Western Union’s communication arm.

An extensive 2012 audit by a French law firm shows Gabon’s ruling family, the Bongos, owning a share of BGFI through a company called Delta Synergie. Gabon is currently run by President Ali Bongo Ondimba, son of Gabon’s former dictator, Omar Bongo.

Chicken deals, Namibian connections, and exotic game

EGAL transferred so much money to these kinds of companies that -- despite the $43 million it received from the Central Bank in 2013 and its tax-exempt status -- the company lost almost $4.5 million by the end of 2014, according to a copy of its financial statement.

So where did the money go?

The records show that a majority -- almost $38 million -- went to three foreign companies: African Trading Maintenance and Development Limited, Samaki (Pty) Ltd., and All Ocean Logistics. All three are run by or associated with Wan and Piedboeuf, their close relatives, or Kabila associates.

African Trading Maintenance and Development Limited, which is based in Hong Kong, received a total of $9.97 million in 20 transfers between June 2013 and June 2014.

In internal documents, EGAL refers to this company as its “poultry supplier,” though OCCRP could identify no tangible trade including that of poultry between the two companies at the time of publication.

A check of the company’s address by OCCRP’s correspondent in Hong Kong found no physical offices. According to Hong Kong Registry documents, the firm is owned by Piedboeuf and Wan.

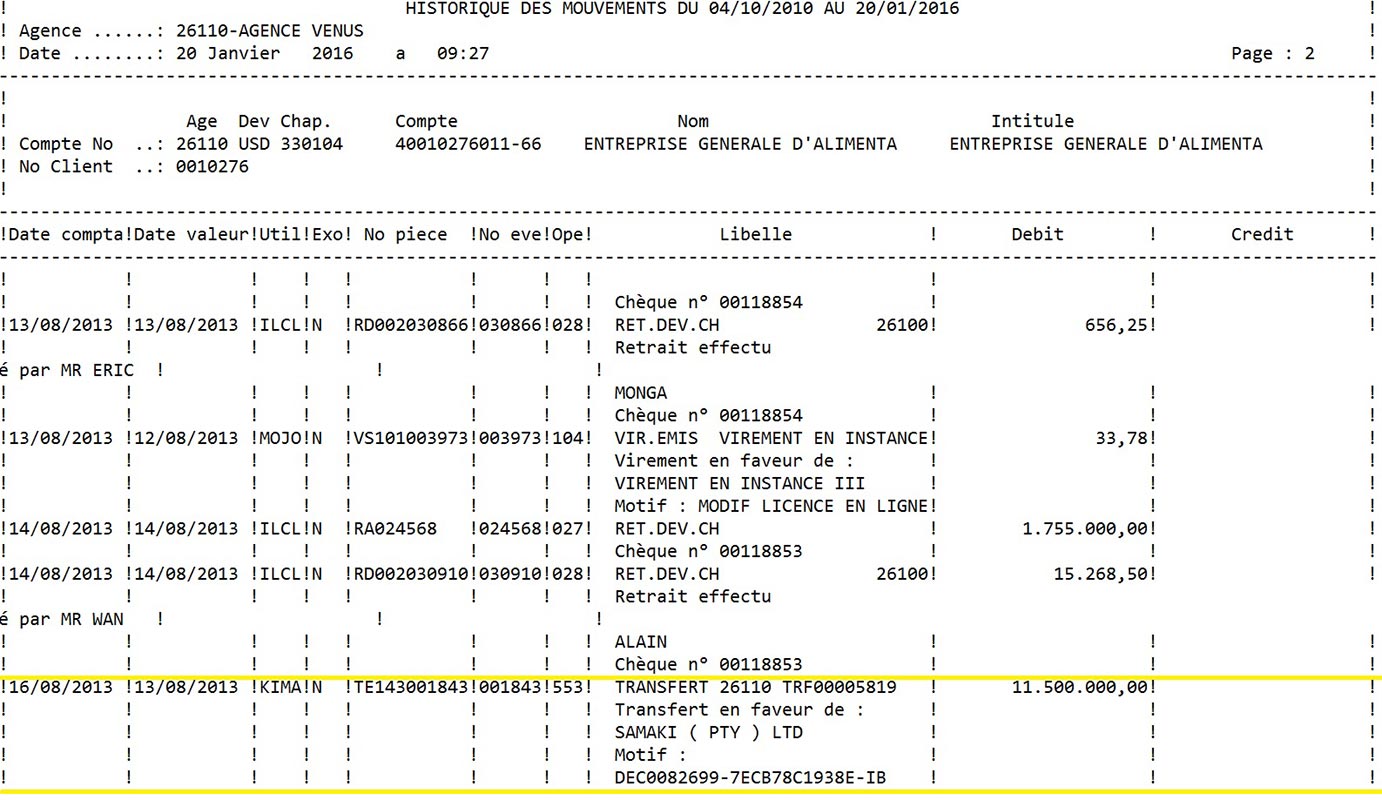

The largest single transfer -- $11.5 million in August 2013 -- was sent to Samaki (Pty) Ltd, a Namibian firm, which, according to EGAL documents, had been appointed as a partner to source and supply competitively priced fish for the company. Including several other transfers, Samaki received $22.8 million from EGAL in total.

A excerpt from a transaction record shows an $11.5 million payment from EGAL to Samaki. (Click to enlarge)Yuma, the EGAL and Central Bank board member, confirmed that Samaki had failed to successfully provide it with Namibian fish, for which purpose the company had allegedly been created. He told OCCRP that Namibia “was the most important supplier to the DRC.” But the company had suffered losses because it became an “intermediary,” instead of having direct access to the fish.

A excerpt from a transaction record shows an $11.5 million payment from EGAL to Samaki. (Click to enlarge)Yuma, the EGAL and Central Bank board member, confirmed that Samaki had failed to successfully provide it with Namibian fish, for which purpose the company had allegedly been created. He told OCCRP that Namibia “was the most important supplier to the DRC.” But the company had suffered losses because it became an “intermediary,” instead of having direct access to the fish.

Yuma insisted that EGAL had only sent $11.5 million to Samaki -- not the $22.8 million that appear in the records. What became of all the money Samaki received is unclear. He claimed that the money was used to pay cash on a continuous basis to several fish suppliers.

The company’s board is nearly identical to EGAL’s – persons in Kabila’s inner circle, including Piedboeuf, Wan, and Yuma.

It is managed by Martha Namundjebo-Tilahun, a politically influential Namibian who is also the owner, president, or board member of various oil, uranium, hotel and banking companies in her home country. Her husband, Haddis -- a Samaki director -- serves on Namibia’s presidential advisory council.

The couple appear to be continuing the intimate relations between the political royalty of the DRC and Namibia. The ties between the two countries aligned in the late 1990s, when Kabila’s late father, Laurent-Desiré Kabila, was president. Sam Nujoma, then president of Namibia, offered the elder Kabila military and diplomatic support in the country’s civil war. In 2001, the Namibian government acknowledged that it had interests in a diamond mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Samaki’s Namibia office did not respond to interview questions, although emails requesting an interview show as having been opened.

Between October 2013 and June 2015, EGAL transferred $5 million to a company called All Ocean Logistics, registered in the Faroe Islands -- a jurisdiction known for its loose tax laws.

This firm’s main shareholder is Andre Wan, believed to be Alain Wan’s son. Until the end of 2015, corporate records indicated its ownership of a cargo ship named El Nino, also in the Faroe Islands.

“He (Alain) instructed his son (Andre) to buy a boat, and they got a cheap one (800 000 EUR),” said an All Ocean Logistics crew member.

The crew member also said that he had met the ship’s former owner and a maritime lawyer from the Faroe Islands who explained to him how they had established the shell company registering El Nino.

“André Wan chose the name of the company. Alain Wan came with a briefcase and the company AOL was born in October 2013.” he said. Alain Wan confirmed that El Nino’s current owner was EGAL, but said that AOL initially acquired it, registering it in the Faroe Islands. This, he told OCCRP, was AOL’s only role.

Since its acquisition by the company, El Nino has been used to ship wild game to places belonging to President Kabila, such as his farm Kingakati near Kinshasa, according to company records and invoices.

Export permits, certificates, and a tax invoice dated May 2017 show over 700 animals, including antelopes, giraffes, Burchell’s zebras, blue wildebeest, waterbucks, and oryx, were shipped from Namibia to the president’s farms. Some of them were transported by El Nino.

"Mr. Kabila has decided to transform a part of Ferme Espoir into a game park modeled around those in South Africa,” Wan told OCCRP and Le Monde.

Invoices for the animals listed Ferme Espoir as the payer and the El Nino as the carrier. The shipments were referenced as “Noah’s Ark.”

There was also unusual maritime activity on El Nino. The ship’s automatic identification system (AIS) or tracking system appears to have been switched on and off along the coast while the ship was shifting goods onto another vessel. Wan responded that another vessel, the Nova Caledonia, was transferring fish to El Nino while out at sea “to avoid the cost of docking and unloading at the dock.”

Namibian authorities authorize and control these transshipments and are mostly on board the ships and issue reports for each operation, he said.

Dr. Ulf Tubbesing, a wildlife veterinarian who works with SuperGame dealers, a company that supplies Namibian wildlife to Ferme Espoir and others, confirmed that, despite the invoices, the bills of the transport of the animals were paid by EGAL. He told OCCRP that no endangered species were involved.

Piedboeuf often attended hunts to catch game in Namibia, Tubbesing said. The veterinarian said that he never met Kabila, but that Piedboeuf and the others told him that the president had a passion for conservation.

“My impression from talking to all his people [during their visits to inspect the farms] was that could be part of his plan to retire from politics - maybe sooner [rather] than later,” Tubbesing said.

Henri Thulliez contributed to this report.

This story is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a partnership between OCCRP and Transparency International. For more information, click here.