It’s got everything: Notorious revolutionaries, corrupt generals, informants and even Uzi machine guns. And a plot to move at least 800 kilograms of cocaine through the private hangar of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, with the expected profits to fund the First Lady’s run for Parliament.

The course of the New York trial was avidly followed from afar.

“It’s unusual,” said Elizabeth Williams, a courtroom artist who illustrated the trial. In 37 years on the job, she said, she’s never seen anything like the online reaction the case sparked in South America. “This is a big case down there.”

Cousins Franqui Francisco Flores de Freitas and Efraín Antonio Campo Flores were convicted last November in a Manhattan courtroom of conspiring to smuggle 800 kilograms of cocaine into the United States. Their sentencing, originally set for March 7, has not yet been rescheduled.

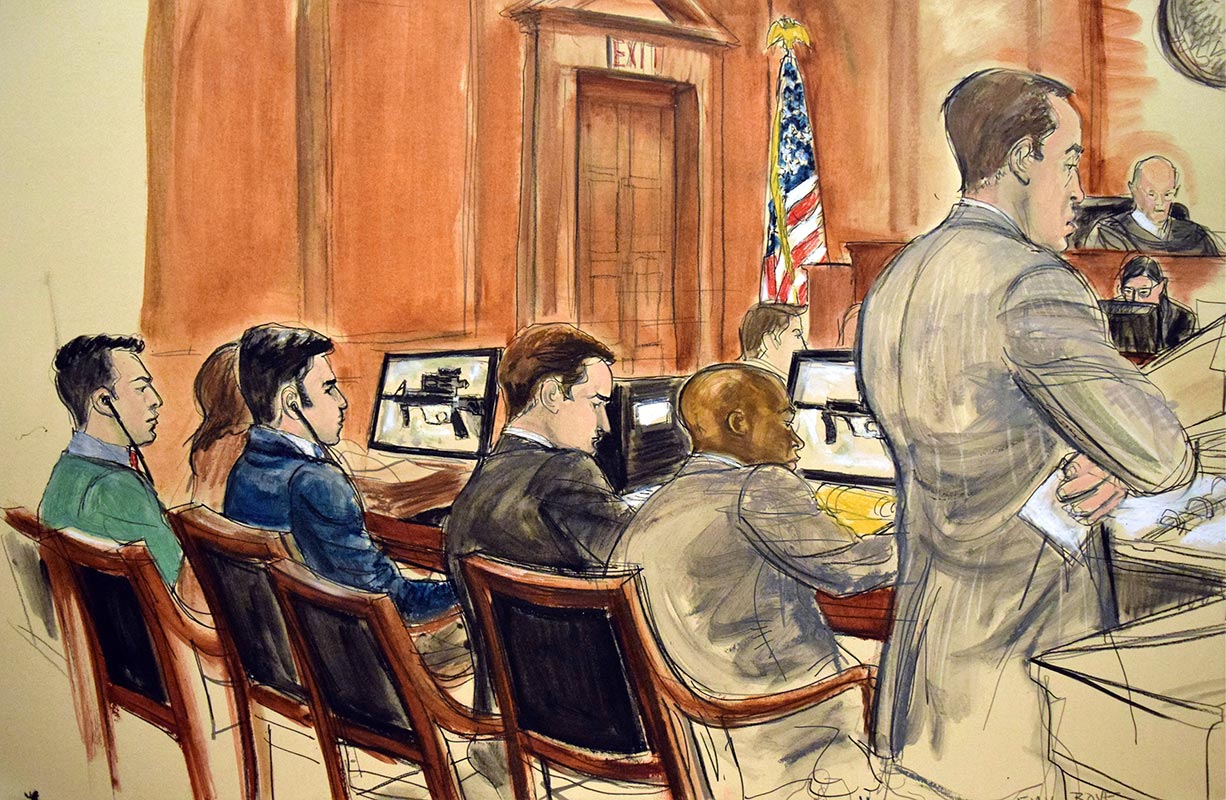

Courtroom artist Elizabeth Williams depicts (from left) Franqui Francisco Flores de Freitas in headphones, defense attorney Elizabeth A. Espinosa, Efrain Antonio Campo Flores in headphones, defense attorneys John T. Zach and Randall W. Jackson and Assistant US Attorney Emil J. Bove, standing. (Associated Press)

Courtroom artist Elizabeth Williams depicts (from left) Franqui Francisco Flores de Freitas in headphones, defense attorney Elizabeth A. Espinosa, Efrain Antonio Campo Flores in headphones, defense attorneys John T. Zach and Randall W. Jackson and Assistant US Attorney Emil J. Bove, standing. (Associated Press)

The story that emerged during their nine-day trial was jaw-dropping.

Flores and Campo are the nephews of Cilia Flores, the wife of President Maduro and a politician in her own right. According to trial testimony, they were planning to move cocaine for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) through Venezuela via the president’s private hangar at the Simon Bolivar International Airport in Caracas.

They expected the deal to bring them as much as $11 million, some of which was to be used to help fund Cilia Flores’ re-election campaign.

The story of how her nephews came to be arrested, tried and convicted illuminates dark corners of “official” involvement in the illegal drug trade in Venezuela -- raising serious questions about the nexus of crime, law enforcement and government in that country.

Prosecutors say that in the months leading up to their arrest, Campo and Flores met repeatedly with traffickers from Colombia, Honduras and Mexico to plan the drug-smuggling operation.

“You will hear Flores brag that he had complete control of the airport in Venezuela,” Assistant US Attorney Emil Bove told jurors in his opening statement. “And he assured the people at the meeting that the drugs would be sent from the presidential hangar at the airport.”

Unfortunately for the nephews, some of their “partners” were informants for the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

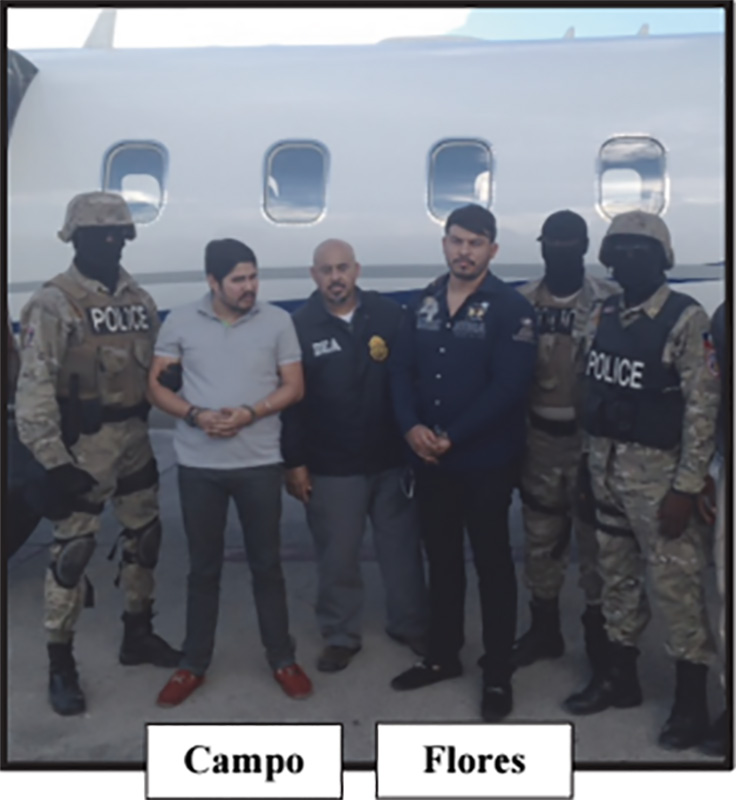

The Colombian cocaine was to be transported through Caracas to an island off Honduras en route to its final destination in the US. On Nov. 10, 2015, the cousins flew to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, to collect their pay for the deal in advance.

Instead, they were arrested by the Haitian police and turned over to US authorities.

Defense lawyers said it was a setup, a DEA sting operation that entrapped their clients, who they called too stupid to have come up with such an elaborate plan.

"These guys, in terms of what actually happened, are idiots, okay?” said defense lawyer Randall Jackson. “They didn't understand what they were getting into.”

Neither defendant was rich, the lawyers said, noting Campo runs a small taxi business, while Flores lives in a two-room apartment.

High-ranking Venezuelan officials have denounced the verdict, calling it a fraudulent attempt to smear Maduro’s family and his United Socialist Party of Venezuela. When her nephews were arrested, the First Lady accused the DEA of “violating our (Venezuelan) sovereignty and committing crimes within our borders.”

President Maduro pivoted to blame the US. “Do you think it’s a coincidence for imperialists to come up with this case with the sole objective of attacking the First Lady, the first fighter, the president’s wife?” he said. “Enough of attacks against revolutionary women, including my wife, Cilia Flores.”

One of the fiercest denunciations came from Diosdado Cabello, a Maduro ally and former president of the National Assembly, who said, “Those boys are kidnapped … in the United States.”

But the US says the denunciations are disingenuous. Media reports accused Cabello of heading the shadowy organization known as the Cartel of the Suns, a drug trafficking network involving mostly high-ranking military officers, a charge Cabello vehemently denies. On wiretaps played in court, rumors of Cabello’s connection with the cartel are discussed.

A deal a long time in the making

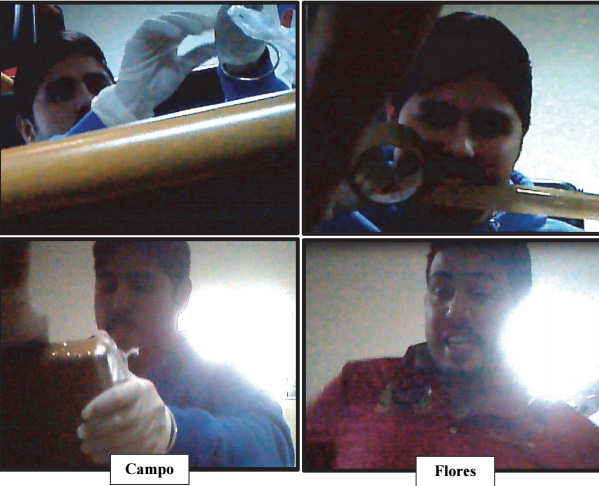

Efraín Campo (in blue) handles a package said to be a kilo of cocaine while Franqui Flores, in red, grimaces. This composite photo was submitted as evidence during the trial. The trail that the two well-connected Venezuelans traveled to a federal courtroom in New York City stretches back to the fall of 2015, although some of the groundwork was laid a full decade earlier.

Efraín Campo (in blue) handles a package said to be a kilo of cocaine while Franqui Flores, in red, grimaces. This composite photo was submitted as evidence during the trial. The trail that the two well-connected Venezuelans traveled to a federal courtroom in New York City stretches back to the fall of 2015, although some of the groundwork was laid a full decade earlier.

In 2005, Venezuela abruptly suspended cooperation with the DEA, when then-President Hugo Chavez accused the American anti-drug agency of aiding drug traffickers and spying.

Mildred Camero, who had been serving as Chavez’s drug czar, was forced from office. Camero, the co-author of the book, “Chavismo, narcotráfico y militarismo” said that Chavez’s move had the effect of opening up the illicit drug trade to more players.

Concurrent changes in the country’s laws gave the Armed Forces authority to fight drug trafficking, an activity that was previously limited to the National Guard, she said. This allowed more military officers to get involved in drug trafficking via the Cartel of the Suns, an organized crime network allegedly controlled by the highest-ranking officers in the military. The group is named after the distinctive sunburst-shaped military insignia worn by generals. “In fact, not only generals are involved, but there are majors, lieutenants, almost everyone in the Armed Forces,” said Camero.

How the scheme was supposed to work

Prosecutors say in the run-up to the drug deal, set for Nov. 15, 2015, the conspirators met six times: three times in Caracas, twice in Honduras and once in Haiti. All of the meetings were surreptitiously recorded.

According to the plan, FARC would deliver the cocaine to Caracas, where it would be loaded onto a plane in the privacy of the president’s hangar before being flown to Honduras. At that point the Mexican partners would take over to move the drugs from Honduras to the US.

In one of the wiretaps, Campo is heard talking with Sinaloa cartel drug trafficker José Santos Peña, identified in court documents as Confidential Source 1 (CS1). In a choppy, interrupted and sometimes inaudible conversation, the two discuss financing Cilia Flores’ campaign; the “war” with the United States; the Venezuelan opposition and the FARC.

[In the transcript, Campo refers to Cilia Flores as his “mother”. She is both his biological aunt and his adoptive mother, as he is the son of her deceased sister.]

Campo tells Santos Peña of his exchange with a FARC guerrilla: “We don’t know each other, but he does know who we are and what … And he is the one who [inaudible] a commander for the FARC. And the guy is supposedly a high-ranked one. I don’t know who he is exactly, but...(inaudible) a very serious person… No, I don’t deal with them directly… Because (inaudible) no, I have a, a guy... No. I placed a person to put me in touch with them.”

Campo tells Santos Peña he needs the money because his mother faces a tough race, despite her strong record in the National Assembly and popularity with voters.

“We need the money. Why? Because the Americans are hitting us hard with money. Do you understand? The opposition... is getting an infusion of a lot of money ... that's why we are at war with them.”

In a surreptitious video recorded at a meeting on Oct. 27, Campo is seen holding a one-kilo “sample” bag of cocaine while Flores looks on. Campo dons gloves to open the bag so that the DEA informants can examine it, and then re-seals it for them with packing tape.

At another meeting on Nov. 6, the conspirators agreed the drugs would be packed in suitcases and Flores said in the recordings that “the plane would arrive clean,” meaning that it would have a registered flight plan from Venezuela.

And then he concluded: “We’re very twisted. We cheat, do stuff and everything. We don't walk straight.”

The day the masks came off

On Nov. 10, 2015, Campo and Flores flew from Caracas to Haiti aboard a Cessna jet piloted by a four-man crew. They thought they were going to pick up $11 million, the advance payment for moving the drugs through the president’s hangar in five days’ time. Once on the ground, they met with agents in a restaurant, where they were arrested.

According to defense lawyers, the cousins’ first thought was that they were being kidnapped by criminals.

Court filings indicate that they “knew many other people who had been kidnapped for ransom; indeed, Mr. Flores de Freitas alone knew more than 15 such individuals, some of whom had been killed by their captors. Given their relationship to the president and first lady of Venezuela, they feared they might suffer a similar fate.”

Agent Sandalio González was responsible for interrogating them. He testified that Campo inquired about cooperating with US investigators, and whether agents were interested in information on money laundering. The agent, however, didn’t record the conversation.

Accounts differ on what happened during a subsequent flight from Haiti to New York. According to the case files, the defendants said they were handcuffed, threatened and told that if they didn’t cooperate, they would spend the rest of their lives in prison.

The detainees said they were hungry and thirsty, but got only water to drink as they were interrogated. They signed Miranda waivers, indicating they had been informed that they had the right to remain silent and anything they said might be used against them in court.

The authorities say they handcuffed the nephews, attached leg irons and treated them according to procedure.

The evidence

Efraín Campo (left) and Franqui Flores (right) were detained in Haiti on 10th November 2015. As the trial unfolded, the cousins presented a dignified front in expensive sweaters. Williams, the courtroom artist, said she was shocked at how preppy they seemed compared to their initial court appearances.

Efraín Campo (left) and Franqui Flores (right) were detained in Haiti on 10th November 2015. As the trial unfolded, the cousins presented a dignified front in expensive sweaters. Williams, the courtroom artist, said she was shocked at how preppy they seemed compared to their initial court appearances.

“They were completely different,” she said. “They were clean-shaven, wearing clothes that seemed like they [came] from J.Crew.”

Flores was the more somber and cautious of the two, mostly frowning and staring straight ahead, avoiding eye contact with journalists.

Campo, on the other hand, seemed more relaxed. He talked with the lawyers and occasionally laughed. But as soon as the prosecution began to sort through the record of his phone calls, his attitude changed, and he grimaced, rubbed his lips and blinked like it was raining.

On the cold November day when key witness Santos Peña testified, tension was thick in the courtroom. The visual contrast was stark between the witness in blue jail scrubs and Campo and Flores, flanked by their six lawyers.

The cousins paid close attention, conferring often, as Santos Peña’s story unfolded.

Santos Peña testified that he is a drug trafficker and that he worked for the Sinaloa Cartel in the 1990s. After his arrest in Mexico in 2000 on kidnapping charges, he became a confidential source for the DEA, but the arrangement fell apart over time as agents accused him of continuing to both lie to them and deal drugs.

He was the main contact with the nephews, meeting with them three times to discuss details of the drug deal. During his four days on the stand, he spoke through an interpreter. Initially, he was calm and confident, but he grew increasingly nervous as defense lawyers accused him of continuing to deal drugs while in jail.

Prosecutors buttressed their case with evidence including wiretaps, videos, photographs and messages from the defendants’ phones. The phones in particular contained photos of private plane trips and expensive weapons, indicating the cousins might not be as poor as defense lawyers had claimed.

On Campo’s phone, for example, one text message said: “One for me and one for my uncle [he didn´t identify the uncle]. US$1,000...Mini Uzi.” The phone also contained a picture of one of the Israeli machine guns.

In the wiretaps, the defendants also discussed their bodyguards, who were to help load the drugs into the plane. Venezuela’s minimum wage is $31 per month; and bodyguards, who usually work in pairs, earn about $88 monthly--a payroll too expensive for most Venezuelans.

For the first month after the arrests, Campo was represented by the high-end international law firm Squire Patton Boggs, allegedly at no cost. The firm withdrew from the case on Dec. 17, leaving both nephews in the hands of New York City public or court-appointed defenders.

However, the defense roster changed again in April when Venezuelan businessman Wilmer Ruperti hired six lawyers to represent the cousins. In an interview given to Wall Street Journal in September last year Ruperti declared that he’s covering the cost.

Ruperti was comparatively unknown in Venezuela until 2002, the year of a major oil strike aimed at bringing down the Chávez government. Instead of joining the strike, Ruperti subverted it, leasing Russian ships so that the national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), could deliver the oil abroad.

Two years later, he paid $1.6 million for two pistols originally owned by Venezuelan national hero, the Liberator Simón Bolívar and gave them to Chávez in 2012. A report from the Spanish press agency EFE indicated that Ruperti acquired the weapons as “a matter of national identity.”

Over the years Ruperti’s client base grew, as did his contracts with the Venezuelan government. On Sept. 29, he announced that he was paying for lawyers. The week previous, he had closed a deal with the PDVSA. Prosecutors produced a copy of a press release announcing that Ruperti’s company, Maroil Trading Inc. received a contract for $138 million.

He says his only motive is patriotism.

He’s paying for Campo and Flores’ defense, he says, so that the judicial proceedings will not disturb the presidential family’s peace. “We need the president to be calm… I’m helping preserve the constitutional government,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

Caracas, Venezuela´s capital, is one of the most violent cities in the world. According to Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia were 28.479 violent deaths in the country during 2016.

Caracas, Venezuela´s capital, is one of the most violent cities in the world. According to Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia were 28.479 violent deaths in the country during 2016.

A scandal-ridden clan

Prior to their arrest, Campo and Flores weren’t the First Lady’s most famous relatives. Carlos Erik Malpica Flores, another of her nephews, is a former head of the Venezuelan Treasury as well as the former head of the state oil company’s finance department.

In November of 2015, he was also the center of an investigation that revealed he owned 16 different companies in Panama.

He appears in court documents in this case as well. Allegedly Malpica Flores rejected a proposal from Campo to “collect commissions, i.e., bribes, from debtors of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)”. (Campo told investigators that his ongoing money worries were one of his motivations for setting up the drug deal).

A previous notorious case surfaced in 2008, when 47 members of Cilia Flores’ family were found to be working in the National Assembly during her time as Speaker of Parliament.

Living the High Life on Social Media

Both defendants were active on social networks. Campo had pictures of a yellow Nissan GT-R and a Lamborghini in his Twitter profile, with a picture of football superstar Lionel Messi as the cover. He also had Snapchat and WhatsApp accounts and had a picture of Hugo Chávez in his Blackberry profile. He even used the initials HRCF for Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías.

Flores’ Blackberry Messenger username was Don Ramón and he had a picture of the clumsy character from the popular Mexican show “El Chavo del 8,” with his trademark shirt and light-blue hat.

According to the court files, the defendants’ phones included contact numbers for “Pepero,” allegedly the middleman for the FARC; and others connected to the deal.

The Cartel of the Suns

Diosdado Cabello is perhaps the highest-ranking member of the Venezuelan government to be mentioned in the case. He has served as acting president of the country and held numerous important government positions over the years.

An article in the Wall Street Journal alleged that he heads the Cartel of the Suns, an allegation that he challenged unsuccessfully in court.

Cabello’s name surfaced in one of the recordings presented at trial. According to one of the transcripts, Flores said: “Diosdado has the [Venezuelan] Armed Forces. He controls them… he has issues with the US and they accused him of drug trafficking.”

The DEA’s cooperating witness then says that he’s heard that Cabello is the boss of the Cartel of the Suns. Flores replies, “They say he is the boss, just rumors. No, I really don't know that, but [Cabello] tells me that he'd be good for president.”

It took six and a half hours for the 12 jurors to find Flores and Campo guilty.

Author Camero is convinced that the involvement of military officers in drug trafficking has increased in recent years. Originally, they simply allowed drugs to be transported through Venezuela, but they eventually became main players of the illegal trade in the country, she says.

Before former US President Barack Obama left office in January, he extended the designation of Venezuela as an “unusual and extraordinary” threat.

Cabello’s response was swift. “Yes, we’re a threat!” he said. “Because we’re socialists, we’re a threat because we’re revolutionaries, we’re a threat because we’re chavista, we’re a threat because we want the people to live in peace!”