Some experts believe El Chapo, a shrewd businessman who had established a strong hierarchy, undoubtedly had a succession plan in place.

The most obvious candidate to carry on Guzman’s legacy and maintain the cartel’s vast power in Mexico is Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, his number two man inside the Federation, with the support of the number three man, Juan Jose “El Azul” Esparragoza.

“I have no reason to believe El Chapo did not have a good succession plan in place, and (Zambada) has likely already taken the reins, with (Esparragoza) at his side,” said Sylvia Longmire, a drug war expert and author of Cartel: The Coming Invasion of Mexico’s Drug Wars.

Still, experts are uncertain about what may happen next with the leaderless cartel and just how much the drug landscape could potentially change in Mexico.

Nathan Jones, the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy and an expert on Mexican drug violence, said the question of what’s next is on everyone’s mind, including analysts at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and those examining the politics of Mexico’s drug war.

Serafin Zambada, son of Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada“Zambada is so essentially recognized as number two—and these guys are all so connected – that this is not going to be that much of a hiccup,” Jones said.

Serafin Zambada, son of Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada“Zambada is so essentially recognized as number two—and these guys are all so connected – that this is not going to be that much of a hiccup,” Jones said.

He believes that a serious disruption of cartel activities would require an unprecedented level of strikes against major “capos” (captains) inside the organization, as happened during the violent breakup of the Tijuana cartel a few years back.

But he doesn’t expect it in this case. “I don’t think there is going to be a power struggle,” he said. “I don’t think he (Esparragoza ) is going to make a grab for power…I think Zambada is going to maintain control.”

James Creechan is a retired sociologist and criminologist who taught at the University of Culiacan in the city where Guzman maintained several houses. He said, “The fact is, nobody knows what is going to happen, and it’s really a great period of uncertainty.”

Creechan said that the recent arrests of Zambada’s two sons by law enforcement in America complicates the question of who takes over Sinaloa.

Vicente Zambada, his oldest son, is now on trial in Chicago, following his 2009 arrest in Mexico City. And younger son Serafin Zambada, who was arrested in November along the Arizona border in Nogales, is awaiting trial in San Diego.

Some sources indicate that Serafin Zambada’s phone records led to Guzman’s arrest, although his defense attorneys adamantly deny that. They further insist that the youngest Zambada is not cooperating with authorities.

Vicente Zamba, Ismael Zambada's eldest sonBut, according to Creechan, Vicente Zambada may be a major roadblock hindering his father’s rise to Sinaloa leader.

Vicente Zamba, Ismael Zambada's eldest sonBut, according to Creechan, Vicente Zambada may be a major roadblock hindering his father’s rise to Sinaloa leader.

“El Mayo himself is under attack, because his son is on trial in Chicago,” Creechan said, and his defense is “Well, my father and I have been working with the DEA to bring the other people down. We’ve been feeding information about our enemies and other people and we have a deal…so you leave us untouched and we will give you the other guys.

He said analysts believe Vicente Zambada is simply grasping at straws in court, but that the recent arrests of Guzman and other Sinaloa leaders might lead some in the cartel to suspect the Zambada family is leaking information to help the sons.

“If that’s happening, nobody working in the drug world is going to trust “El Mayo” and his family,” Creechan added.

Zambada faces three possible futures, Creechan believes: he could kill all of his enemies and take the throne by force; he may be forced to take the number one seat; or he could be killed by Sinaloa colleagues who no longer trust him.

Creechan believes Zambada’s negatives are too high for him to prevail: “I don’t see him taking over because of all the other things.”

Violent Turf Battles Expected To Continue

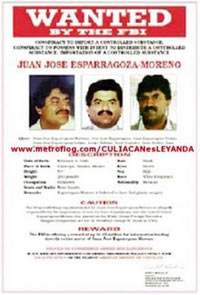

Wanted poster for Juan Jose "El Azul" EsparragozaFor years, the Mexican drug cartels have been fighting over territory and crucial distribution routes to move their product in and out of the country.

Wanted poster for Juan Jose "El Azul" EsparragozaFor years, the Mexican drug cartels have been fighting over territory and crucial distribution routes to move their product in and out of the country.

The violence has led to more than 60,000 deaths since 2006.

Now, with the largest cartel in Mexico decapitated, experts believe there is a potential for escalated violence from other cartels, which may look to capitalize on Sinaloa’s momentary weakness stemming from Guzman’s arrest.

Currently, Sinaloa controls much of western Mexico along Baja California and major trading routes in the south and north, while embroiled in bitter conflict with groups like Los Zetas, the Beltran Leyvas, Cabelleros Templarios, La Familia Michoacan and others.

George Grayson, a professor at the University of William & Mary and an expert on the Mexican drug wars, said he doesn’t believe groups like the Cabelleros Templarios and La Familia Michoacan present much of a threat due to internal divisions and recent struggles with a civilian paramilitary force that is challenging the cartels in their stronghold territories.

“A lot of the cartels are split, and others have their hands full,” Grayson said.

The experts think Los Zetas are the most likely candidates to escalate violence against Sinaloa. Said Jones, “If anyone is going to smell weakness, it’s going to be Los Zetas.”

Los Zetas were formed as an elite body guard unit to protect the Gulf Cartel in the 1990s, but broke away in 2010 and soon became the second strongest drug cartel in Mexico, employing violent and brutal tactics which included beheadings, hangings and wholesale slaughter.

Jones believes the Zetas could combine with their allies, the Beltran Leyvas and the Carrillo Fuentes organization, to strike at the heart of Sinaloa.

Longmire, the author, agreed the Zetas were the most likely candidates to escalate violence, but felt it would be limited and brief because at present Sinaloa “is too large and too powerful to be completely taken over as a whole.”

“The violence may temporarily increase in places where (Sinaloa) is already in conflict with other cartels like Los Zetas, but I think that will ease back to normal levels once things readjust,” she said, citing areas like Nuevo Laredo where the groups are “fighting for control of lucrative drug smuggling corridors.”

The Big Picture

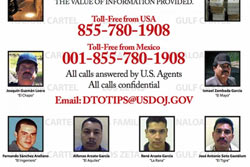

Wanted poster for major cartel leadersProfessors Grayson and Jones believe that the intelligence gained from Guzman’s arrest could potentially lead Mexican and U.S. authorities to other leaders like Zambada and Esparragoza, which would mean a huge disruption for Sinaloa.

Wanted poster for major cartel leadersProfessors Grayson and Jones believe that the intelligence gained from Guzman’s arrest could potentially lead Mexican and U.S. authorities to other leaders like Zambada and Esparragoza, which would mean a huge disruption for Sinaloa.

Jones said if this happens, violence would likely spike as Sinaloa breaks down from losing multiple leaders in quick succession.

Creechan believes Guzman’s arrest is part of a larger initiative by Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto that marks a change from the previous administration of former Mexican President Felipe Calderon and his party.

“The government… (is)going to be quite willing to live with a lot of little cartels and a lot of little gangs in the sense that these little gangs may do local damage (but)can’t do much in terms of warfare,” he said. “In a way it’s a kind of a Colombian strategy.”

In 2012, Nieto hired Oscar Naranjo, the former head of the Colombian National Police and a retired general. Naranjo broke up major cartels in Colombia to stabilize the country, subsequently ending their reign.

Creechan said that Nieto could be using Naranjo to do likewise in Mexico, breaking up the major cartel networks while leaving smaller, weaker organizations in place as he enacts reforms to open up Mexico’s oil market to the world.

Since August of 2013, Nieto has been working to convince foreign firms to form partnerships with the state-owned oil monopoly, Pemex. But investors have been reluctant due to widespread reports of corruption, thefts and involvement by drug cartels in the oil business.

“Nieto is trying to convince the world to invest in Mexico, particularly in Pemex,” Creechan said. But “if I’m an investor, a foreigner, there is no way I am going to touch Pemex.”

In 2012, a Pemex investigation found more than 5,000 illegal siphons, leading to the loss of 3 million barrels of crude oil that cost the company US $475 million, according to an article in In Sight Crime.

The previous year, Pemex had reported an increase in thefts of crude oil by drug cartels including Sinaloa and Los Zetas which then sold the stolen oil on the black market.

“Nieto opened up Pemex to the world, now he’s got to sell it,” Creechan said. “And I am sure the take-down of the cartel bosses is to say ‘No, we really are in charge.’”