Meanwhile, Georgian officials point to the weak protection laws as evidence of their “business friendly environment.”

JSC Imeri is a Georgian-owned factory that produces high-end women’s coats for major Italian and Germany clothing companies. LTD Georgian Textile is a Turkish-owned company that supplies the LC Waikiki clothing store chain.

A reporter worked for two days in each factory in August. Hired on a trial basis, the reporter did not identify herself to managers as a journalist. The reporter learned that unpaid overtime work is routine and neither factory gives its workers the number of holidays required under Georgian law.

The reporter also learned first-hand that conditions can be harsh in the summer heat, with dust-filled air, poor ventilation, few opportunities for water or toilet breaks and some supervisors who don’t speak the Georgian language.

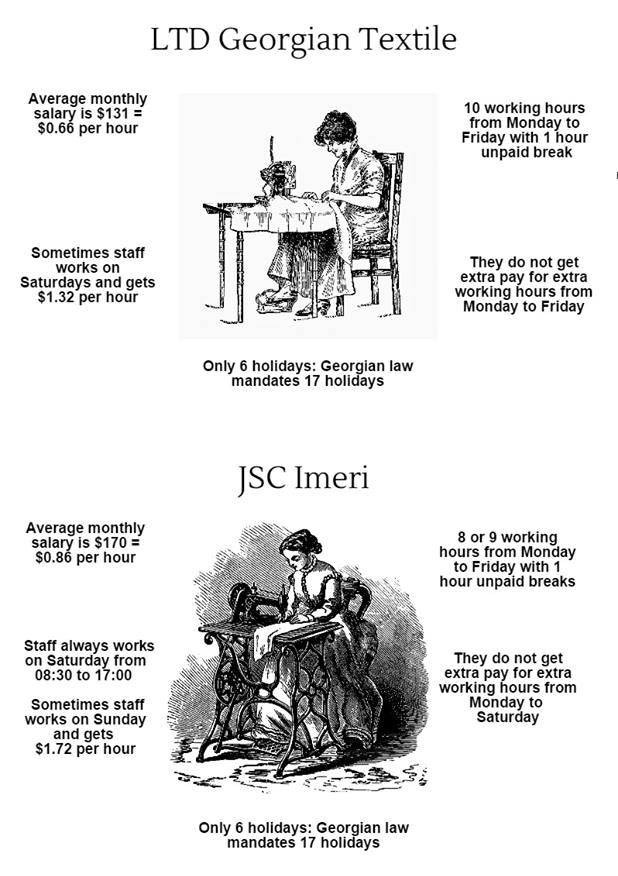

According to the Georgian Labor Law passed in 2013, factory workers should receive overtime pay if they work more than 48 hours a week. Neither JSC Imeri, with a regular six-day work week, or LTD Georgian Textile which works five days, pay overtime for hours worked on regularly scheduled days, although the workers are required to stay extra hours on the job several nights a week until the daily production quota is met.

The labor law requires that workers receive 17 holidays each year. At these two factories, workers receive only six holidays.

At least JSC Imeri and LTD Georgian Textile don’t violate Georgia’s minimum wage law. That would be almost impossible. The minimum wage has been $11.50 a month since a 1999 decree by former president Eduard Shevardnadze.

That’s not to say wages are high at the two Kutaisi factories. At LTD Georgian Textile, the average wage is 66 cents per hour. At JSC Imeri, it’s 86 cents per hour.

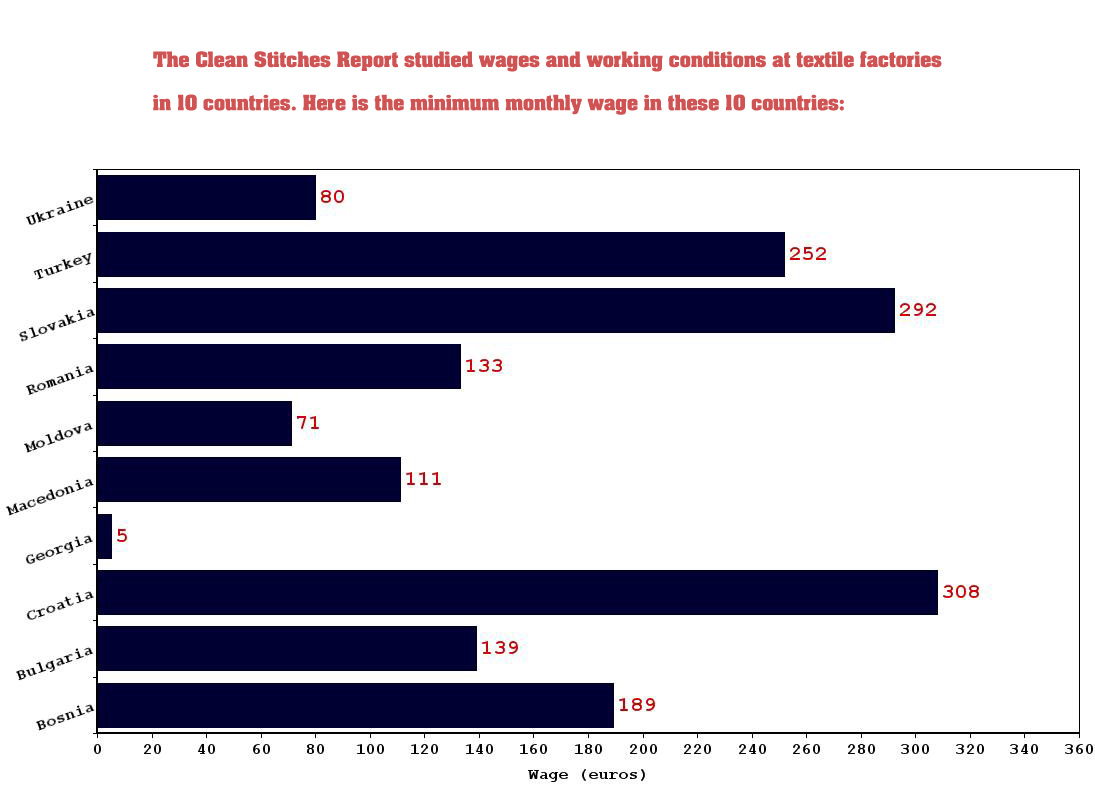

The Clean Clothes Campaign, a European worker-advocacy project, in May released “Stitched Up,” a survey of the textile industry. It included factories in Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Macedonia, Moldova, Ukraine, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovakia and Georgia. Only Georgia had no realistic minimum wage.

Ukraine’s was the next lowest at € 80 per month (US$ 101); Croatia was highest at € 308 per month (US$ 390). The survey singled out Georgia as a country where a “legal rights protection system and institutional mechanisms such as labor inspection and labor court barely exist at all.”

What is the Georgian government ’s position on such labor issues?

A 2012 letter sent out to potential investors under the signature of former Prime Minister Nika Gilauri neatly summarizes the National Movement Party’s business-friendly policies while they ruled the country from 2004-12: “Favorable logistics, rather cheap labor, low and flat taxes, efficient export regimes and additional investment incentives initialed by the Georgian Government lead the country to be the hub of the apparel industry.”

Labor has fared no better since the Georgian Dream party came to power in 2012. Former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili held few significant meetings with labor representatives. Current Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili is chairman of the Tripartite Commission, a mediation mechanism made up of representatives from government ministries, companies and labor. But the commission hasn’t met for more than five months.

Three labor bills are being prepared for discussion by Parliament. None of them include a new minimum wage, and they contain very few specifics on a Georgian government commitment to reinstate workplace inspections, which were halted by the government in 2005 as part of the campaign to make Georgia extremely business-friendly for outside investors. A five-year, US$ 2 million US Department of Labor grant is designed to assist the Georgian government in setting up a system for inspections of workplace conditions. This initiative is opposed by pro-business advocates within the Georgian government.

JSC Imeri

Gvantsa, 22, drew several patterns on cloth, and trainees had to follow those lines as they learned how to sew. One of about 350 workers, she quit school in the ninth grade and for the past seven years has worked at Imeri, starting her job six days a week at 8:30 am. On good days she finishes at 5:30 pm, but when the daily quota has not been met, she must stay until perhaps 7 pm or 7:30 pm with no extra pay.

There’s been a textile factory in this building for 85 years. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgians took control. The current director is Giorgi Chikhladze. Chikhladze is on the floor every day, checking for speed and quality of the work. Employees say that if they complain, he tells them if they don’t like it here, then quit. Workers paid under a dollar an hour produced baby coats that Moncler sells for $325.

Workers paid under a dollar an hour produced baby coats that Moncler sells for $325.

Imeri has two major contracts – with the German company Barbara Lebek and the Italian company Moncler. While the reporter was working, Imeri was producing three styles of women’s coats, and also blouses and trousers, for Barbara Lebek. Imeri was producing baby coats for Moncler that were priced at €257 (US$ 325) on the company’s website; the factory was producing more than 100 baby coats a day.

The workers usually can make quota working six days a week, but occasionally must also work on Sunday, in which case they receive double pay ($1.72/hour). Depending on the orders, they may get as much as four weeks paid vacation in August.

The sewing machines are located in one huge hall, about 10 meters wide and more than 100 meters long. The ceiling is more than four meters high. Three walls are painted dull gray. The fourth wall has windows two meters high that are always open on hot summer days. There is one water tap in the room, where workers are allowed to fill bottles.

Employees are divided into six work teams, each with a foreman who often yells at them to work faster. There are three break times: 10-10:15 am, 12:30-1 pm and 3:30-3:45 pm. The women’s toilets are located so far from the work floor that it’s impossible for 300 women to use them during these short breaks. There is a small café, but it is hot and noisy.

One group of workers does not sew, but is responsible for checking the finished products for pencil marks and loose threads before packaging. These workers have no chairs and must stand all day, and their salary is slightly lower than those who sew.

LTD Georgian Textile

LTD Georgian TextileLTD Georgian Textile has a Turkish manager, Adil Sari. His father, Nuri Sari, is the owner of LTD Georgian Textile and another factory in Batumi.

LTD Georgian TextileLTD Georgian Textile has a Turkish manager, Adil Sari. His father, Nuri Sari, is the owner of LTD Georgian Textile and another factory in Batumi.

About 250 workers start when a bell rings at 9 am. Until the workday ends, usually at 7 pm, workers are not supposed to use their phones or even speak, unless it is to ask a foreman or a fellow employee a work-related question.

The workers are divided into two teams, each with a Georgian foreman who often yells at them to work faster. There is also a Turkish head foreman, but that person doesn’t speak Georgian. While the OCCRP reporter was working there, his interpreter didn’t show up; co-workers said that happens often.

If the workers don’t make quota, which happens several times a week, they must stay after 7 pm for no extra pay. There is no air conditioning, and temperatures in Kutaisi in August can reach 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). The hot air is full of lint from the fabric. By the end of the day workers’ arms were black with lint.

The normal work week is five days. There is one break from 1-2 pm. There is no café, just a small, dirty room with three small tables. There is only one toilet apiece for men and women, with no soap or any way to dry hands.

The work force is divided between two rooms, each about seven meters wide and 70 meters long with a four-meter high ceiling. There’s one drinking water dispenser for all to share. The outside walls for both rooms are constructed of glass block; a few blocks have been removed, letting only a little bit of air into the room.

The fixed salary works out to about $91 a month, or 56 cents per hour. Bonuses for perfect attendance, making quota, and quality of the product often bring that total up to about $125 a month. If Saturday work is required, workers get double pay ($1.32/per hour). Depending on orders, workers might receive paid vacation in August.

The company’s main customer is LC Waikiki, a company founded in France in 1985. It’s been based in Turkey since 1997 and is a division of LC Waikiki Mağazacılık Hizmetleri Ticaret A.Ş.

The company says it now has 475 retail stores in 22 countries. In August this factory was making women’s jackets that sell for about US$ 17.

Union Struggles

Garment workers in Georgia organized their first union in 1906 and succeeded in getting an increase in wages and a decrease in hours.

More than a century later, there are 26 apparel factories in Georgia and only two of them belong to the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC) garment division.

JSC Imeri is one of the two companies with union workers. GTUC garment sector deputy director Klara Macharashvili said the union has failed in several attempts to unionize LTD Georgian Textile.

“We negotiated with Georgian Textile’s workers in 2011, and initially they accepted our offer,” Macharashvili said. “After several days, they decided against becoming members because their employers threatened them.”

Nona Kakabadze, the financial manager at Georgian Textile, says there are reasons why their workers do not want to become union members. “We have former teachers and policemen working here who were members of GTUC, but they didn’t get any support from GTUC when they were fired from those jobs,” Kakabdze said. “They do not want to pay over $1 a month now for a GTUC membership. People at GTUC think that we threaten those people, and that is why they reject membership. I cannot dictate to them what is wrong and what is right. They are adults and they can decide everything themselves.”

Macharashvili says Georgian Textile managers refused to let her enter the factory’s main hall when she visited in July. She said she had received anonymous phone calls and decided to try to inspect the factory herself.

“They do not get extra payment for extra hours,” Macharashvili said. “Management tried to convince me there was a fair bonus system. But it was not clear how the bonus system worked. I sent an official letter about salaries and working conditions to Nuri Sari, the Turkish owner of the factory. But (I received) no reply.”

The union says it does what it can for its members at JSC Imeri. “We know that salaries at Imeri are not high, but we cannot demand more,” she said. “The contract prices between Imeri and the European companies are low. The Europeans know we pay low wages, which is why they are here.

“People accept it because they have no choice. This money is probably very important to their family. But I think that when a new investor comes into the country, the government should make them put minimum rights in the contract.”

Macharashvili says nothing happens when the union reports wage and working condition complaints to the labor policy department of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Social Affairs. Ivanidze, acting director of the department, disagrees and says they have a close partnership with GTUC.

The department was created in 2013, shortly before a new labor bill passed that did not mandate a higher minimum wage. Ivanidze says the government currently has no tools to control either local or foreign businesses operating in Georgia. He hopes the new legislation will at least lead to the formation of a Labor Inspection Department in 2015, with regional offices to follow, and create a system for fining companies that fail the inspections.

“The minimum salary in our country is $11.50 a month,” Ivanidze said. “So the salary in the factories you have mentioned seems to be quite good compared to the law now. I know the main attraction of our country is cheap labor and no labor legislation.”

Maia Simonidze, chairwoman of JSC Imeri’s council board, has an office in the factory and comes to work every day. “When we started negotiations with the Italian company Moncler, we tried to increase the contract price. Now we are waiting for a new partner to appear. Moncler’s representative is aware that when a new company will appear, we will end our partnership with Moncler.

“But thanks to Moncler, we kept two of our teams working. Nowadays we have this problem; we are looking for qualified staff so we can increase our productivity. Salaries make up 60-70 percent of our expenses. If we were more productive, we could increase salaries.

“Our labor market in Kutaisi is too small. A large number of women have left Kutaisi and gone to European countries to find jobs. They send money home. So their family members do not want to work at a factory from early morning to evening and get maybe $200 per month.”

Kakabadze says the minimum wage at Ltd Georgian Textile was defined by oral agreement with the previous (United National Movement) government. “When Turkish owners launched the company in Adjara, they were not aware of the regulations in Georgia,” claimed Kakabadze. “The government told us that $70 should be the minimum monthly salary.

“Nowadays we know how to pay salaries and no one from the government intervenes in our business.” Ivanidze confirms that the government does not negotiate with new businesses over minimum wages.

Ivanidze says he hopes the 2014 signing of the Association Agreement with the European Union will lead to Georgia raising its labor standards. Kakabadze from LTD Georgian Textile says it’s possible that if the standards are raised, the European companies will leave the market.

“It will be harmful to our workers, who will lose their jobs,” she said. “I know a salary around $170 isn’t great, but if I do not have any other income, it is not bad. I can cover at least some of my expenses with this money.”

Questions e-mailed twice to the home offices of Barbara Lebek, Moncler and LC Waikiki asking what they know about the wages and working conditions in their Kutaisi factories have yet to be answered.