A key component of the devices is a special sensor that’s produced in only a handful of countries — not including Russia. That’s why, for years, the country’s military has had to rely on imports. And with the introduction of US and European sanctions following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow’s inability to produce the sensors domestically became a national security concern.

The story of one attempt to tackle this problem by creating a new technology company is a telling example of how public-private partnerships tend to work in Russia.

Reporters for Novaya Gazeta, a partner of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), looked into the details.

The financing for the new firm, which was supposed to fill this crucial missing link in the Russian arms industry, came both from a private investor and from state funds.

But the private investor, hidden in opaque offshore jurisdictions, put up only a fraction of the needed capital. The remainder — to the tune of 85 percent — was supposed to come from the state.

And it may be no coincidence that three people intimately involved in the setup of the company, and who were set to profit from its operations, are closely related to senior government officials.

One is the son of an FSB general. One is the son of the director of a state scientific research institute. And the third is a man Dmitry Rogozin, until May deputy prime minister in charge of the country’s defense industry, has referred to as his nephew on multiple occasions (though he later denied the relationship). This May, Dmitry Rogozin was appointed director general of Roscosmos, a state company overseeing the Russian space program.

Through a series of offshore deals involving the private investor, a company connected to two of these men managed to obtain a significant percentage of the new technology firm — though they had put up almost no money for the project themselves.

In the end, the project failed. Though tens of millions of dollars had already been invested, much of the promised government financing did not come through.

The company still exists, but to this day — five years later — it has not succeeded in mass-producing its own sensors.

A Mysterious Offshore Investor

Back in 2012, Dmitry Rogozin, a deputy prime minister who supervises the Russian government’s Military-Industrial Commission, promised that the country would soon stop being dependent on imported thermal imaging sensors.

“For now, we’re not producing sensors for our Russian thermal imagers, but in a year we will be. The government has already given all the orders to our manufacturers, and I’m sure they’ll be fulfilled. In a year, we’ll have our sensor,” said Dmitry Rogozin, exhibiting his usual confidence, on the Russia 24 TV channel in 2012.

A year later, in September 2013, a new company intended to fulfill Rogozin’s order was registered in Shchyolkovo, a city near Moscow.

The firm, called simply Fotoelektronnye Pribory (“Photoelectronic Devices”), was located in a building belonging to Tsyklon (“Cyclone”), a state scientific research institute and one of the few Russian enterprises that already manufactures thermal imagers, albeit with imported sensors.

By contributing the right to use its property — valued at 385 million rubles (US$ 11.6 million) — Cyclone received a 50 percent stake in the new enterprise.

The other 50 percent of Photoelectronic Devices belonged to an offshore company, registered in Cyprus, called Rayfast Investments.

Rayfast, in turn, was owned by a Panamanian company called Bluebell Investments Trading, whose beneficiary was a wealthy businessman named Konstantin Nikolayev. He was the private investor behind Photoelectronic Devices.

But in several deals that took place over the next few months, Rayfast was split in a way that essentially gifted half of the firm, along with millions of rubles, to another offshore company, this time registered in Panama, called Baron Commercial.

This meant that one quarter of Photoelectronic Devices now belonged to Baron. And, as reporters learned from a leaked email archive (see box), the people behind this company were two young men closely related to senior officials: Alexander Tarasov and Alexey Beseda.

The Email Leak

In 2014, unknown hackers broke into Alexey Beseda’s mail.ru email account. Few paid attention to the hack over the next few years, until Novaya Gazeta reporters noticed an article in The Intercept that was based on documents found in the archive.

One of The Intercept’s staff put Novaya Gazeta in touch with the person who had passed along the emails.

They contained both correspondence and documents that detailed the transactions around Rayfast Investments and arrangements being made for the financing of Photoelectronic Devices.

Reporters verified these documents through publicly available sources and also got in touch with several people who appeared in the email correspondence, including Alexey Beseda. None denied its authenticity.

Little is known about Tarasov — except that, at the time, he was the deputy general director of Cyclone, the state institute that owned half of Photoelectronic Devices. He worked there under his father Viktor, the institute’s general director.

The other young man, Alexey Beseda, occupies an almost contradictory position in contemporary Russia: He is a modest and unassuming son of an FSB General.

The General’s Son

After the outbreak of war in southeastern Ukraine in 2014, one of the prominent Russians who found themselves under US and European sanctions was General Sergey Beseda, allegedly the overseer of the unrecognized Donetsk People’s Republic on behalf of the Russian secret services.

The FSB general’s son Alexey had first became known to the wider public in 2013, when the Russian daily newspaper Vedomosti reported that, at the age of just 26, he had acquired 4.3 hectares of expensive land and a two luxury homes in the Moscow Region. (His neighbors there included the head of Russian Railways, the president of Transneft, and the head of Rostec — all extremely large and influential state firms.)

By what means could a recent graduate of Moscow State University’s foreign affairs department acquire such real estate? That remains a mystery.

But despite his evident wealth, Beseda’s acquaintances characterize him as a modest young man.

“Why do journalists even care about him? He's a regular guy,” one of them told reporters. “He lives with his family in a [two-bedroom apartment] in the city center and drives a regular car. From what I understand, he’s not a ‘silver-spoon-in-the-mouth’ type, though there could be something I don’t know.”

Another acquaintance said that Beseda “doesn’t throw extravagant parties, goes to regular Moscow bars with friends, and never mentions his high-ranking father.”

This image is confirmed by Beseda’s emails and his internet presence, where he doesn’t come off as the son of an influential government strongman. His social media accounts boast no photographs of chic cars or luxury interiors, he sells his used possessions second-hand on the internet, and he is registered on Couchsurfing (a service where users can stay, for free, as one another’s guests). Beseda subscribes to the fashionable publications The Village and FurFur, and follows the opposition account “Peskov’s Mustache” and the Dalai Lama on Instagram.

In fact, nothing in Alexey Beseda’s public appearance indicates that he exploits his father’s powerful position.

It’s the assets he owns that say otherwise.

A Gift Worth Hundreds of Millions

The email discussions that shed light on how Photoelectronic Devices was apportioned —and how it was meant to be financed, largely by state funds — began in the summer of 2013.

In addition to Tarasov and Beseda, the third party in the exchange was a representative of Konstantin Nikolayev, the private investor behind the new firm.

In one of his emails, Tarasov writes Nikolayev’s managers that “this project requires around 2.5 billion rubles. You are providing less than 400 million (roughly 15 percent), and the remaining two billion or more come from businesses and collateral from the other party [state companies]. This is an unhealthy disparity.”

One might think that in this email Tarasov was defending the interests of the state companies that were providing the most financing and collateral for the new venture. After all, he worked for one of them. But that’s not the case.

In fact, judging from a complicated and lengthy series of emails, it’s clear that he and Beseda were advocating for larger benefits on behalf of Baron Commercial.

Why would he do this? Reporters could not confirm who owns the Panamanian company, but the only plausible explanation is that Tarasov and Beseda had an interest in the firm — which, within a few months, had come to own one quarter of Photoelectronic Devices, essentially for free.

This was arranged through a strange series of financial maneuvers.

First, on Dec. 6, 2013, just a few months after Photoelectronic Devices was registered, Nikolayev’s Bluebell Investments Trading sold Rayfast Investments (which owned 50 percent of the new technology firm) to Baron Commercial for $10,000.

Then, just four days later, Baron sold half of Rayfast to Rubyshine Ventures, a firm registered in the British Virgin Islands, for 187 million rubles ($5.7 million). According to documents from Alexey Beseda’s emails, the beneficiary behind Rubyshine was also Nikolayev.

In effect, Nikolayev had sold a company for $10,000 and then bought back half of it for 570 times more. And Baron, the Panamanian company tied to Beseda and Tarasov, obtained a 25 percent stake in Photoelectronic Devices and almost 200 million rubles — all for next to nothing. According to official Rayfast documents, this money was invested back into the founding capital of Photoelectronic Devices.

When contacted by reporters, Nikolayev did not explain the economic rationale behind the deal. Alexander Tarasov did not answer phone calls and refused to comment through an intermediary.

Alexey Beseda’s email archive ends abruptly in the summer of 2014. Since then, the ownership structure of Rayfast Investments changed several more times, until, by 2016, Alexey Beseda was left as its sole owner. As such, the son of the FSB general now owns half of Photoelectric Devices.

Dmitry Rogozin at a May 2018 press conference with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Rogozin was recently made director general of Roskosmos, and from 2011 to 2018 deputy prime minister with oversight of the country’s defense industry. Credit: Grigory Dukor / Reuters

Dmitry Rogozin at a May 2018 press conference with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Rogozin was recently made director general of Roskosmos, and from 2011 to 2018 deputy prime minister with oversight of the country’s defense industry. Credit: Grigory Dukor / Reuters

Promised From On High

The Nephew

Not only did Rogozin refuse to comment on whether he was lobbying on behalf of his nephew — he denied he had a nephew at all.

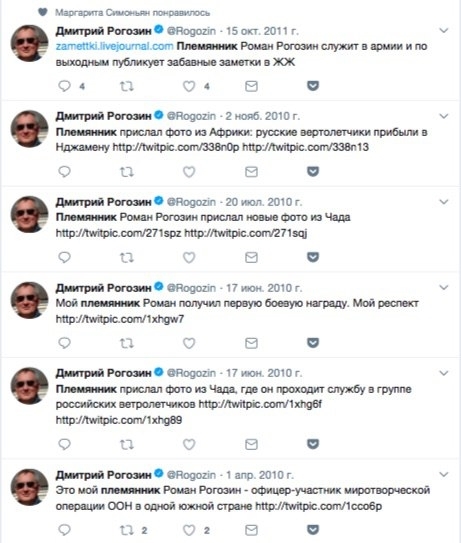

How can one prove otherwise? Of course, Russian government officials don’t keep public lists of their relatives, but journalists investigating corruption can use other sources — chiefly, social media. From 2010 to 2011, Dmitry Rogozin mentioned “his nephew Roman” online six times.

For example, in October 2011 he wrote: “My nephew Roman Rogozin serves in the military, and on weekends writes funny posts in LiveJournal.” In June 2010, Rogozin senior wrote that he was “proud of his nephew who got his first military award” and attached a photo of the relative in question.

The photo corresponds with an image of Roman Rogozin in Novaya Gazeta’s possession which shows him among the board of directors of the thermal imaging sensor production facility. The date of birth of Rogozin’s “nephew” also matches that of the businessman from Photoelectronic Devices.

A few weeks after contacting Rogozin for comment, his spokeperson Nikita Anisimov reached out to reporters to tell them that the “deputy minister has never had a nephew named Roman, and doesn’t have a nephew at all.” Anisimov refused to clarify what Rogozin had meant in his repeated mentions of his relative on Twitter.

The email archive reveals still more about how Photoelectronic Devices was meant to be financed.

Alongside Beseda and Tarasov, another young relative of a high-ranking official was involved in the project. Emails from the leaked archive indicate that, from the moment of its founding, a man named Roman Rogozin sat on Photoelectronic Devices’ board of directors.

Dmitry Rogozin — the deputy prime minister who had first announced that Russia was working on its own thermal imaging sensors — has referred to Roman as his nephew several times on his Twitter account.

In the email archive, one text discussed by Tarasov and Beseda was a draft of a formal letter addressed from Dmitry Rogozin to the director of VneshEkonomBank, a state-owned bank. The text requests a loan from the bank for Photoelectronic Devices. Rogozin refused to comment to Novaya Gazeta as to whether he was lobbying on behalf of his nephew. In fact, he denied that he had a nephew at all (see box).

Following this exchange, posts about Dmitry Rogozin’s nephew Roman started vanishing from his social media accounts. Nevertheless, some of them are still available in Google Cache.

In any event, in 2015, the factory manufacturing sensors for thermal imagers became part of a government support program for investment projects, making it eligible to receive large government loans. The website of the Ministry of Economic Development details the loan profile: VneshEconomBank was to loan 2.3 billion rubles ($36.5 million) to Photoelectronic Devices at an 11.5 percent annual interest rate. The loan was guaranteed by two state companies: Ruselectronics (controlled by Rostec, the owner of Cyclone) and Cyclone itself.

Meanwhile, the liabilities of the private investor, Rayfast, were limited to the promises to make additional investments “in case of unforeseen circumstances” (this was the wording used in the loan application).

Instances of Dmitry Rogozin describing Roman as his “nephew” on his personal Twitter account. In 2015, Russia’s Industrial Development Fund allocated a separate loan of 500 million rubles for the project at an annual interest rate of five percent.

Instances of Dmitry Rogozin describing Roman as his “nephew” on his personal Twitter account. In 2015, Russia’s Industrial Development Fund allocated a separate loan of 500 million rubles for the project at an annual interest rate of five percent.

But a source familiar with the project told Novaya Gazeta that, at the last moment something went wrong, and that while VneshEconomBank’s loan had been approved by the ministry, it was never paid out. According to this source — later confirmed by a VneshEcomBank employee — Roselectronics refused to provide loan collateral at the last second.

A military project of strategic importance for the country — which had already received almost a billion rubles from state companies — had fallen through.

In December 2015, Viktor Tarasov, who had served as director of Cyclone since 1996, left the company.

Alexey Beseda refused to talk to Novaya Gazeta, saying that he didn’t see any evidence of corruption in the episode.

A Matter of Honor (And Profit)

What, then, do we know about Konstantin Nikolayev and his motivations — given his important role in this complex scheme?

“I had a couple of meetings with him,” began a minority partner for one of Nikolayev’s projects who asked to remain anonymous. “He gave the impression of being a very friendly and open person. I don't know how he manages to be a successful businessman at the same time.”

Nikolayev’s success might be the result of his skillful choice of business partners. He built up his first big company with billionaire Alexey Mordashov, the owner of Russian steel giant Severstal. Together with Arkady Rotenberg, a longtime friend of President Putin, he constructed a motorway through the Khimki Forest. Nikolayev also shared ownership of an oil transport company with another good friend of Putin, the businessman Gennady Timchenko.

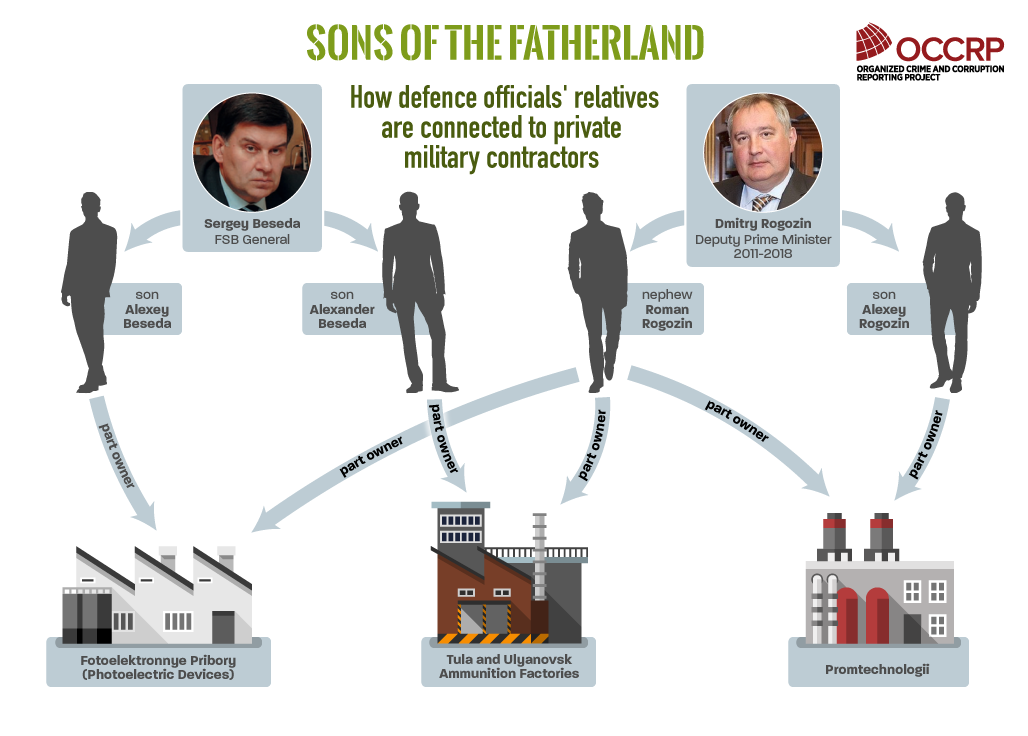

Producing thermal imaging sensors is not the first instance of Nikolayev partnering up with relatives of general Beseda and deputy prime minister Rogozin.

In 2010, he became co-owner of Promtechnologii, the company that controlled Orsis, a major rifle company based in Moscow. And ever since Promtechnologii was established, Dmitry Rogozin’s son Alexey has been the company’s deputy general director.

In 2012, when Dmitry Rogozin was appointed deputy prime minister and supervisor of Russia’s military-industrial commission, a scandal erupted about the conflict of interest.

In an emotional post on his Facebook page, Rogozin wrote: “At a family meeting, my son and I took the difficult decision that he leave the company to avoid any speculation about a conflict of interest,” he explained. “Our family has always, for centuries, been involved with the army. For us honor, integrity and reputation are more than just words.”

But after a while, Rogozin’s son was replaced by Roman Rogozin, the elusive nephew.

Meanwhile, Promtechnologii was expanding. In 2012, the company acquired a share in two ammunition factories in Tula and Ulyanovsk. After that, first Alexander Beseda, the second son of FSB general and Alexey’s brother, became a board member, followed by Roman Rogozin, who took Beseda’s position on board a year later. Over the last five years, these factories have sold ammunition worth almost two billion rubles to various law enforcement and military agencies.

Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP

Still Dependent

In July 2016, the Ministry of Defense held an event showcasing new advances in weaponry and military technology over the past year. After all the time and money spent on its development, Cyclone’s new director Alexander Borisov announced that his institute had finally created a prototype of a Russian thermal imaging sensor. “We have received prototypes that conform to international standards, and have launched the production of microdisplays with an output up to 10,000 a year” he declared.

The Cyclone Institute has new management — it seems they want to manufacture sensors for thermal imagers without any private investors.

However, Cyclone’s press service later clarified to Novaya Gazeta that Borisov had been wrong, and that production had not yet been launched. According to Cyclone’s 2016 annual report, it was still importing “microbolometer sensors of the required format” to produce the thermal imaging devices.

The Russian armed forces, it seems, will have to wait a while longer.