Aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska — a one-time business partner and employer of Paul Manafort, the embattled former campaign chairman for US President Donald Trump — was one of hundreds of wealthy individuals who have applied for Cypriot nationality. His application was approved last year.

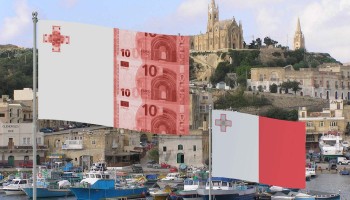

Gold for Visas

For the past six months, reporters with a dozen OCCRP partner organizations have investigated the growing popularity of Golden Visas, which allow the world’s wealthy — including tax evaders, criminals and corrupt officials — to buy their way into new countries. In cooperation with Transparency International, they found that these programs are pumping huge revenues into cash-strapped countries which often cloak the whole process in secrecy. This story is just the first of many; read more on OCCRP.org on Monday, March 5.

The island also offered citizenship to Viktor Vekselberg, another Russian billionaire and a major shareholder in the largest bank on Cyprus, the documents show. Vekselberg appears to have turned down the offer, with his spokesman insisting Thursday that he holds only Russian citizenship.

Documents obtained by OCCRP and The Guardian include several hundred individuals who have taken advantage of programs that allow high-net-worth individuals to acquire Cypriot citizenship and, with it, the right to freely travel, work, and settle in the European Union.

Originating more than 30 years ago in the Caribbean, such schemes — known in the industry as “Golden Visas” — have spiked in popularity in the past decade and are now offered in more than 20 countries. They have been criticized for allowing wealthy people, including those who have obtained their wealth illegally in countries with weak legal systems, special access to life in developed countries that is not available to others.

As reported by The Guardian last September, the Cyprus version of the program requires investment of €2 million in property, or €2.5 million in companies or government bonds, in exchange for citizenship.

Paul Manafort, former campaign chairman for U.S. President Donald Trump, departs after a bond hearing as part of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's ongoing Russia investigation, at U.S. District Court in Washington, U.S., December 11, 2017. Photo (c): Reuters / Joshua Roberts According to figures provided to the Cypriot parliament on Monday, since 2008, Cyprus has awarded citizenship to 1,685 foreign investors — many from the former Soviet Union, as well as from China, Iran and Saudi Arabia — and 1,651 of their family members. The investment inflow from the scheme is estimated at more than €4.5 billion.

Paul Manafort, former campaign chairman for U.S. President Donald Trump, departs after a bond hearing as part of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's ongoing Russia investigation, at U.S. District Court in Washington, U.S., December 11, 2017. Photo (c): Reuters / Joshua Roberts According to figures provided to the Cypriot parliament on Monday, since 2008, Cyprus has awarded citizenship to 1,685 foreign investors — many from the former Soviet Union, as well as from China, Iran and Saudi Arabia — and 1,651 of their family members. The investment inflow from the scheme is estimated at more than €4.5 billion.

The program has come under widespread scrutiny from watchdog NGOs and some politicians.

“All [EU] member states that sell citizenship to the highest bidder must ensure that applicants are subject to the sharpest of checks,” said Naomi Hirst, senior campaigner at Global Witness, an anti-corruption organization.

“This is not just about the risk of dubious characters with dirty money finding safe haven in Cyprus. If the source of wealth and the background of these individuals is not sufficiently scrutinized, then the whole of the European Union could be made vulnerable to those who will use these schemes as a ‘get out of jail free card’ and a means to move freely around Europe,” she said.

Ana Gomes, a Portuguese member of the European Parliament, described the Cypriot program as “absolutely perverse, immoral and increasingly alarming.”

Last year, the European Commission has launched an inquiry into such programs in the EU which is expected to be finalized later this year. Cyprus is one of the countries under scrutiny.

“Cyprus is the biggest European investor in Russia and a great number of Russian nationals acquired Cypriot passports,” Gomes said. “We are all aware that there is also a big problem of recycling money. The point is that Cyprus, like other countries, is not just selling its passport. It is marketing European citizenship.”

Indeed, a trove of more than 400 names obtained by The Guardian and OCCRP confirms the extent to which Cyprus’s citizen-by-investment program has become an avenue for wealthy Russians to obtain EU passports. About one-third of the names on the list appeared to be Russian.

It also raises serious questions about the background checks carried out on applicants by Cypriot authorities.

Deripaska and Vekselberg — two of the most prominent names on the Cyprus list — were both included on a Jan. 29 list of 210 Russian officials and wealthy businessmen believed by the US Treasury Department to be close to Putin. While not a sanctions list, the names were assembled as part of a sanctions package signed into law the previous August.

Russian officials have derided the list as simply a “telephone directory” of rich Russians intended to damage their reputations and sow doubts about doing business with them, while Trump’s political opponents have blasted the list as falling well short of serious sanctions.

A History of Visa Problems

Deripaska, whose net worth has been estimated at $6.6 billion by Forbes, has global business interests ranging from agriculture to aviation to automobiles. He has had previous difficulties in obtaining visas due to alleged ties to organized crime, which he strenuously denies.

For example, The Guardian reported in 2008 that the billionaire had failed to obtain a US business visa in 1998, although he was subsequently allowed to visit the country in 2000 after employing former US Sen. Bob Dole to lobby on his behalf. The FBI interviewed him during that visit, however, and reinstated the ban on US visits.

According to the New York Times, Deripaska nevertheless managed to make eight visits to the US between 2011 and 2014, traveling as a Russian diplomat with Moscow’s permission.

Deripaska also has a previous history in Cyprus. In 2016, he had applied for a Cypriot passport through the island’s collective investment scheme, which allowed a group of individual investors to band together, contributing a minimum of €2.5 million each, for a minimum total investment of €12.5 million. His application was denied.

Documents seen by OCCRP and The Guardian indicate why Deripaska's first attempt to become a Cypriot citizen was unsuccessful. He was asked to resubmit his bid amid allegations from Belgium that he had been involved there in money-laundering. Deripaska denies the claims.

Russian tycoon and President of RUSAL Oleg Deripaska attends a lecture during the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the Swiss mountain resort of Davos January 22, 2015. Photo (c): Reuters / Ruben Sprich

Russian tycoon and President of RUSAL Oleg Deripaska attends a lecture during the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the Swiss mountain resort of Davos January 22, 2015. Photo (c): Reuters / Ruben Sprich

At that time, those who applied as individuals were required to acquire Cypriot assets worth at least €5 million, which could include companies, real estate, securities, government bonds, or even bank deposits with a three-year maturity.

On Sept. 13, 2016, the country’s Council of Ministers revised the visa process by cancelling the collective scheme and reducing the eligibility threshold for investors to €2 million.

As the Cypriot government was weighing Deripaska’s initial application, officials were notified by European authorities that he had been investigated in 2015 by Belgian officials in a money-laundering case involving art and property worth “tens of millions.”

Deripaska responded by presenting a letter from the Bureau of the Royal Commissioner of Brussels on July 27, 2016, saying that “the case was archived and because of lack of evidence it was not further pursued.”

That October, the Cypriot Council of Ministers decided to further investigate the allegations and to re-submit his application for a final decision at a later stage. Deripaska’s new application was filed on March 24, 2017 and ultimately approved.

But, though Deripaska’s new Cypriot passport enables him to travel freely around the European Union, it will not necessarily get him into the US. Cyprus is currently awaiting approval for inclusion in the US Visa Waiver Program, which allows citizens of 38 countries to travel to the US without a visa.

An easier route to the EU: banking

A second and even richer Russian billionaire, Viktor Vekselberg, appeared to have an easier time getting at least the offer of a Cypriot passport. According to a request filed by the country’s Minister of Interior to the Council of Ministers on March 27, 2017, he was granted Cypriot citizenship via an “honorary naturalization.”

Under Cypriot law, the Council of Ministers can grant such naturalizations in very exceptional cases of high-level services offered to the country, or for reasons of public interest. This was the case with three Greek athletes and a Romanian trainer who competed for Cyprus in various venues from 2008 to 2010.

In Vekselberg’s case, it appears to be his considerable investment into the Bank of Cyprus that won him the offer.

Vekselberg is the owner and president of the Renova Group, a large Russian conglomerate active both in the country and abroad.

Chairman of the Board of Directors of Renova Group, Viktor Vekselberg attends a session during the Week of Russian Business, held by the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP), in Moscow, Russia February 7, 2018. Photo (c): Reuters / Sergei Karpukhin

Chairman of the Board of Directors of Renova Group, Viktor Vekselberg attends a session during the Week of Russian Business, held by the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP), in Moscow, Russia February 7, 2018. Photo (c): Reuters / Sergei Karpukhin

The Lamesa Group, which a spokesperson said “is affiliated with” Renova, is also owned by Vekselberg. In August 2014, Lamesa contributed to the Bank of Cyprus’s €1 billion capital increase.

That was the year now-US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross was elected vice chairman of the bank, together with Vladimir Strzhalkovskiy, a former KGB official and Putin ally. In 2015, upon resigning as board member, Strzhalkovskiy sold part of his stake to Vekselberg. Ross resigned from the bank after he was confirmed in the Commerce post in 2017.

As of Jan. 19, 2017, Lamesa was directly or indirectly the owner of 9.3 percent of the bank’s shares, making it the largest single shareholder.

“[The Lamesa] investment took place during a difficult period for the economy of Cyprus, when foreign investment was [the only hope] for recovery and investors could hardly demonstrate confidence in the Cypriot economy,” reads the interior ministry document.

Furthermore, “as an indication of his commitment to the Cypriot economy, Vekselberg indicated interest in further increasing Lamesa Group’s shareholding in the Bank of Cyprus and the request is under review by the authorities in charge.”

Despite his investments, Vekselberg’s spokesman Andrey Shtorkh was adamant in a written statement Thursday. “Mr. Vekselberg has only one citizenship — of [the] Russian Federation and was never granted any other citizenship, including Cypriot.”

According to the interior ministry document, Vekselberg is also a citizen of both Russia and Ukraine. He owns the world’s biggest collection of Fabergé eggs and his personal wealth is estimated by Forbes to be $14.9 billion.

He was among the attendees of a December 2015 dinner in Moscow for the Kremlin TV channel RT, where Trump’s future national security adviser Michael Flynn was photographed seated next to Putin. Vekselberg was also in Washington during Trump’s inauguration ceremony 13 months ago, according to the Washington Post.

With additional reporting by Tanja Milevska.

This story is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a partnership between OCCRP and Transparency International. For more information, click here.