Russian authorities have angrily denied that “Novichok,” a substance blamed by the British authorities for poisoning a former Russian military intelligence officer in the United Kingdom, has ever existed.

But new evidence unearthed in Russia shows not only that an entire group of substances called Novichok did indeed exist, but that some was obtained by criminals after being produced in a government lab as late as 1994 — and has since killed at least two people.

Reporters for Novaya Gazeta, a partner of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), tracked down records from a sealed 1995 criminal case in which a Russian banker and his secretary were murdered using a poisonous substance.

Two specialists who have worked with Novichok independently confirmed to reporters that the toxin described in the investigation was one of several varieties of the Novichok agent.

The case materials show that enough of the poison to create hundreds of potentially lethal doses had fallen into the hands of criminals. A separate criminal case against the man responsible for distributing the substance was labeled “top secret” and never resolved.

Novichok Resurfaces

Sergei Skripal, Novichok’s most recent alleged victim, has lived in the United Kingdom since being convicted of espionage by the Russian government and traded for Russian “sleeper agents” in a prisoner exchange with the United States. His daughter Yulia was also poisoned in their home in the English city of Salisbury, but she is recovering.

The British authorities have declared that Novichok was used in the attempt on Skripal’s life. They blame the Russian government of either being complicit in the attack or of allowing the substance to fall into the hands of the attackers.

Moscow has angrily denied any role in the affair. In response to the British accusations, the Russian government declared that all Soviet chemical weapon development programs were halted in 1992, and that by 2017 any remaining stockpiles had been destroyed. Furthermore, authorities have said that no compound called Novichok ever existed.

“No scientific research programs under the name ‘Novichok’ were carried out in the Russian Federation,” Vasily Nebenzya, Russia’s permanent representative to the UN, said at a Security Council meeting.

Sergey Ryabkov, Russia’s deputy foreign minister, has also insisted that no programs for the development or production of chemical weapons under the name ‘Novichok’ existed, either in the Soviet Union or Russian Federation. The ministry’s official spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, has repeated these claims on Russian television channels.

But according to documents from Russian criminal case 238709, work with a substance of this nature continued “in the period before 1994” and the equivalent of hundreds of lethal doses was given or sold to violent criminals in 1994 and 1995. In the case files, the identity of the substance is referred to as a state secret. However, specialists contacted by reporters identified it as belonging to the Novichok group.

Murder By Telephone

The case began in August 1995, after the sudden death of Ivan Kivelidi — then head of a private bank called Rosbusinessbank — and his secretary, Zara Ismayilova. Both were found to have been poisoned.

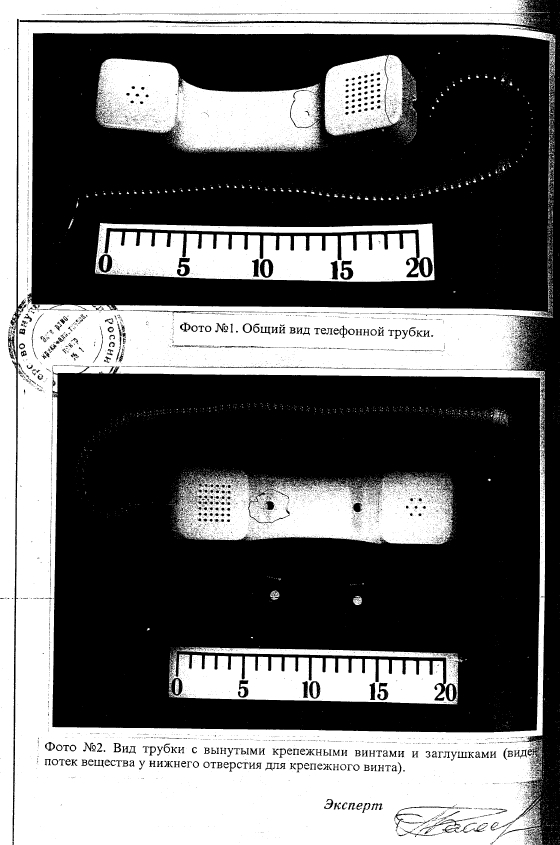

An investigation of Kivelidi’s workplace and of the objects in his office revealed that the poison had been placed beneath the rubber cap, just over five millimeters in size, that covered a screw in his telephone receiver. The substance was used in very small quantities and left a barely noticeable trace.

The banker Ivan Kivelidi, killed by a mysterious chemical substance in 1995. Photo from YouTube A forensic medical examination concluded that “upon contact with bare skin, the contaminated telephone receiver caused damage which proved fatal.”

The banker Ivan Kivelidi, killed by a mysterious chemical substance in 1995. Photo from YouTube A forensic medical examination concluded that “upon contact with bare skin, the contaminated telephone receiver caused damage which proved fatal.”

The substance that had poisoned him was clearly of unusual potency. Despite the tiny dosage, the case materials describe it also striking Kivelidi’s bodyguard, visitors to his office, witnesses who were summoned to the scene, a cleaner, and eight police officers. All suffered symptoms of varying degrees of severity.

(The same thing happened in Salisbury, where not only Skripal and his daughter, but also police officers who arrived at the scene of the incident, were affected. One officer required intensive hospital care.)

Investigators looking into Kivelidi’s murder asked three government agencies to analyze the substance.

Both the Ministry of the Interior’s Expert Center for Criminology and the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute for the Environment and Evolution derived the same chemical formula from samples obtained at the scene. In its expert report, the latter noted that “a substance with such a structure belongs to the class of highly-toxic organophosphorus-based compounds used in the production of chemical weapons.”

Another agency, the State Scientific Research Institute for Organic Chemistry and Technology (GOSNIIOKhT), also gave an expert appraisal and reached a nearly identical conclusion, only adding that the substance also contained fluorine.

The expert reports produced by the three agencies (1,2,3) contained detailed descriptions of the poison’s chemical formula, allowing reporters to take them to two independent specialists for analysis.

Vil Mirzayanov is a chemical weapons specialist who has long experience with the Novichok family of poisonous substances. He was the first to reveal the existence of Novichok in the early 1990s, and published their formula in his book about Soviet chemical weapons programs.

The telephone receiver from Kivelidi's office, with residue of the poison highlighted. Photo from case files. In his opinion, the substance used in Kivelidi’s poisoning belonged to the Novichok group. “It is Novichok,” he told Novaya Gazeta. (Mirzayanov emphasizes that it is possible, in principle, to identify the country of origin of such a substance by identifying the origin of the substances used to synthesize the final product.)

The telephone receiver from Kivelidi's office, with residue of the poison highlighted. Photo from case files. In his opinion, the substance used in Kivelidi’s poisoning belonged to the Novichok group. “It is Novichok,” he told Novaya Gazeta. (Mirzayanov emphasizes that it is possible, in principle, to identify the country of origin of such a substance by identifying the origin of the substances used to synthesize the final product.)

A second expert who has worked with Novichok also told Novaya Gazeta anonymously that the substance in the case was of the Novichok type.

Soon enough, investigators discovered where it may have come from.

In the course of their investigation, they learned from the FSB Directorate of the Saratov Region that a senior employee at the State Institute of Organic Synthesis Technology (abbreviated GITOS in Russian), a facility in the closed city of Shikhany, had engaged in the “unsanctioned synthesis” of a poisonous substance in 1994. (Notably, according to a Reuters report last week, a British intelligence briefing identified a facility in Shikhany as the origin of the nerve agent that poisoned Skripal)

As reported by Novaya Gazeta, an FSB employee who testified before investigators said that GITOS was “a secret enterprise whose employees signed agreements on the non-disclosure of state secrets, including when working with potent and poisonous substances.” This was where the Soviet Union’s chemical weapons program was based and where Novichok and its variants were invented and manufactured.

Given that Kivelidi had been killed by such a substance, this piqued the investigators’ interest into what was going on behind the closed doors of Russia’s secret laboratories — and in the man who had sold substances produced there.

Professor Rink

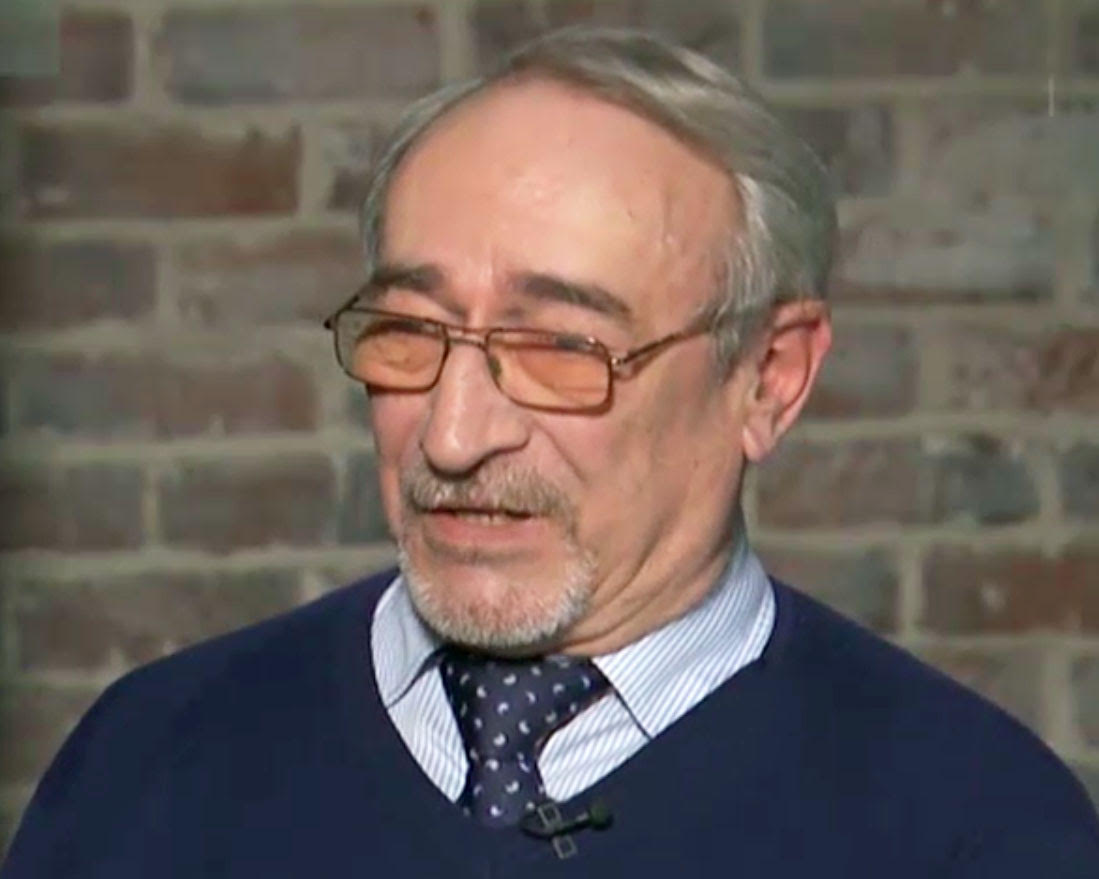

That man was Leonid Rink, a chemist described in case files as a “head of a GITOS unit.” Investigators pulled him into the Kivelidi murder investigation as a witness, questioning him repeatedly and in detail, over several years, about the development of the poisonous substance and about his role in distributing it.

A Telling Correction

Leonid Rink has been outspoken in the Russian media about the recent controversy — though one prominent interview carried an interesting correction.

“Novichok is not one substance; it’s a whole system of applying chemical weapons,” the state news agency RIA Novosti initially reported Rink as saying. “The system adopted by the Soviet Union was called ‘Novichok-5.’ The name wasn’t used without [accompanying] digits.”

Soon after, however, these quotes were removed and replaced with a denial of any program under such a name: “It’s absurd to talk about a ‘Novichok’ formula, and about a project under that name.”

In the same interview, the scientist said that the British could have poisoned Skripal themselves.

An industry colleague of Rink’s describes him as a professional with impeccable qualifications in the field of highly toxic compounds, noting that “you can count the number of specialists of that caliber on your fingers.”

According to his testimony, Rink didn’t work alone. In 1994 — two years after Russian officials said that chemical weapons agents had ceased being made — he brought in a colleague to help him synthesize the substance, telling her that it was required by the military.

“I warned [my colleague] that she shouldn’t discuss this with anyone … This was an ‘unofficial’ order, and I didn’t want any third parties to know. She didn’t object, since I told her that she would be paid for the work, and she really needed the money,” Rink said during his interrogation.

“The substance I wanted to obtain ... is labelled a state secret. … In terms of its toxic impact, it is similar to VX [a highly toxic nerve agent],” Rink added. “We poured it out into vials, about 0.25 grams each. … I took the vials home with me and put them in my garage.”

It’s not clear exactly how many vials Rink took with him. According to files from a separate top secret criminal investigation launched against him as a spin-off of the Kivelidi case, he had made “8-9 vials” and, on Sept. 13, 1995, gave some to “individuals of Chechen origin in the city of Moscow.” But that case was closed after it was found that these sales occurred after Kivelidi’s death, and Rink faced no consequences for the delivery. No other explanation for closing the case was given.

Criminal Elements

Tiny but Deadly

According to a specialist who took part in Rink’s interrogation, 0.25 grams of the substance would be enough to poison 100 people.

“If applied to the skin, only a hundredth of the amount contained in a vial would be enough to kill a person weighing around 80-90 kilograms,” he said, according to the interrogation document.

During interrogation, both the specialist and Rink confirmed that the substance was top secret and that it was produced at GITOS.

Two other specialists contacted by reporters who were knowledgeable about Novichok said that if the substance was produced correctly and sealed in a vial, it would remain effective even after 25-30 years of storage. While they acknowledged that it would lose strength over time, the dose needed to kill someone is so minimal that it would be effective even at reduced strength.

The original case mentions nothing about Chechens. But the case files do contain testimony about the eventual fate of some of the vials Rink took home.

He initially told investigators that in 1994, he gave one of them to a man named Ryabov who had initially told him he wanted to poison a dog, but then “said that the poison was needed not for a dog, but for a person.” However, in court testimony in 2007, Rink said that he had given Ryabov four vials and that they were eventually seized by the Federal Security Service.

Rink said that Ryabov had started to threaten him. “I was afraid of Ryabov’s threats; [he] was connected with criminal elements. … [so] I agreed to get this poison for him,” he told investigators in 2000.

In the spring of 1995, according to a file from the investigation, Rink sold another vial to Artur Talanov, who lived in Latvia at the time — as the document puts it, “for self-defense.”

Leonid Rink, a former GITOS lab director who synthesized and marketed a poison substance, according to his testimony. Photo from YouTube. “Some people needed the substance to settle [their] gangster disputes,” Rink explained in 2007 court hearings. “They found out where my relatives live. Ryabov came to my home, and I had to buy him off somehow. First I gave him something simple, I thought that would be enough. Then something more serious.”

Leonid Rink, a former GITOS lab director who synthesized and marketed a poison substance, according to his testimony. Photo from YouTube. “Some people needed the substance to settle [their] gangster disputes,” Rink explained in 2007 court hearings. “They found out where my relatives live. Ryabov came to my home, and I had to buy him off somehow. First I gave him something simple, I thought that would be enough. Then something more serious.”

Talanov subsequently took part in an attempted robbery on a cash delivery van in Estonia, where he was shot and seriously wounded.

But — at least according to the investigation — the vial Talanov bought ended up in the hands of Vladimir Khutsishvili, a long-time acquaintance of the murdered banker and former board member of Rosbusinessbank. Khutsishvili was eventually convicted of Kivelidi’s murder in 2007 — as the investigation saw it, he was in the banker’s office at a time when poison could have been applied to the telephone receiver.

Khutsishvili’s legal counsel insisted that he had been in plain sight of the secretary and bank employees when he was in the office, and could not have put the poisonous substance into the telephone receiver. In order to avoid being fatally poisoned himself, continued the defense, he would have needed at least a pair of thick rubber gloves and a respirator.

The fate of the other vials Rink took home is unknown. He declined to comment for this story.

Hard Times, Desperate Measures

In his testimony, Rink said that he had given the recipients of the vials detailed information about how the poison works and how to use it safely.

“The substance takes effect upon contact with the skin, or when it enters the body in food. … I said that the signs of death would resemble heart disease. The dose of the substance in the vial was sufficient to lethally poison a person,” he said.

“When you handed over the substance you had prepared… did you understand that you were handing it over to be used against a person?” asked the prosecutor.

“Yes, I understood that [they] were planning to use the substance on people,” acknowledged Rink.

Understanding why Rink may have acted as he did requires understanding Russia in the 1990s, when life was hard — especially in closed cities and secret institutions that relied on government funds. They had no money and salaries sometimes went unpaid. Employees came to work looking for ways to survive.

The closed towns of Shikhany-1 and Shikhany-2, Saratov Region, Russia. Satellite image from Google Maps

The closed towns of Shikhany-1 and Shikhany-2, Saratov Region, Russia. Satellite image from Google Maps

In his testimony, Dmitry Ayatskov, former governor of Saratov Region, recalled meeting with enraged GITOS workers whose salaries had not been paid: “Once … at a meeting in the institute’s club, one of the women threatened to cover the porch of the regional administration building with such a poisonous substance… As a result, I got the idea that GITOS was manufacturing some chemical poisons,” the governor told the investigation.

For the hundred doses of the substance contained in the vial he sold Talanov, Rink received “from US$1,500 to $1,800,” according to his testimony.

In July 2004, law enforcement within the Kivelidi murder case decided to halt the criminal investigation against Rink and those he sold the poisonous substance to (on the illegal preparation, acquisition, storage, transport, and sale of potent and poisonous substances), as the statute of limitations for criminal prosecution had expired.

In 2007, during court hearings for the case, the defendant’s lawyer asked Rink about the other, top-secret case against him, in which he had been accused of taking 8-9 vials home. However, the court dismissed the question.

In protest, the lawyer said: “The question was regarding … the number of vials with a military-grade poisonous substance, which were sold and ended up wandering the world, including in Moscow, in an unknown quantity and with unknown people, and could have been used in a crime.”

The question was never answered, and neither the court records nor the criminal files indicate any further information about the fate of the vials.