As part of the indictment, an extensive investigative report by the Public Prosecutor’s Office at the Court of Palermo reveals new details of an alleged web of relationships and deals between criminals and state officials. On March 6 2013, a judge in Palermo found there was sufficient evidence in the report for the trial to proceed. If the prosecution’s allegations are proven, then 25 years of Italy's political history will be rewritten, with potentially enormous repercussions.

According to the prosecution, representatives of the Italian government and the Sicily-based La Cosa Nostra held a series of negotiations in 1992 and 1993, reaching a final agreement in 1994. Prosecutors allege the government consented to repeal certain anti-Mafia laws and ease prison regulations against Mafia inmates in exchange for a halt to the killings and bombings that roiled Italy between the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s.

Unlike similar reports in other countries, which are generally limited to the crimes under consideration, the Palermo prosecutors’ report is wide-ranging, addressing not only the crimes to be tried but the historical context and even the cultural influences involved.

The road to ‘repentance’ Prosecutor Antonio Ingroia led the investigation over the pact between state officials and mafia members.

Prosecutor Antonio Ingroia led the investigation over the pact between state officials and mafia members.

The prosecutors’ report alleges that the roots of the “State-Mafia pact” lie in a complex web of relationships between Mafiosi and officials dating back more than two decades. According to the report, drastic regional political changes in the 1980s, including the collapse of Communism, led to radical social, financial and political changes in Italy. One such change involved La Cosa Nostra. Whereas the state had tended to tolerate and, in some cases, legitimize the presence and power of the criminal organization, officials believed it was time to cut the ties and show the public they were committed to moving against the Mafia.

At the time, La Cosa Nostra was not only a criminal organization but an entire criminal system, relying on its solid connections with Italian political and financial elites.

Efforts like the Palermo “maxi-trial”, 1986-87, held in a purpose-built bunker, dealt a devasting blow to the Sicilian crime syndicate by imprisoning numerous affiliates along with several top figures, demonstrating publicly that impunity, once virtually guaranteed for Mafia members, was over. In Italy, the maxi-trial is widely considered the first important strike by the state against the Mafia. The sentence read on Dec. 16th 1987 involved 475 defendants, of whom 360 were found guilty of 120 crimes, totalling 2,665 years of prison. The crimes included Mafia affiliation as well as murder, drug trafficking and extortion.

The maxi-trial would have not been possible without the cooperation of former Mafia boss Tommaso Buscetta, the first major “pentito” in Italian Mafia history. The term (literally “repentant”) describes a Mafioso who collaborates with authorities’ investigations. Becoming a “pentito” is among the most disgraceful things that a Mafia member can possibly do; their ‘honor’ code forbids collaboration with authorities under any circumstances. The punishment for such betrayal is death: not just for the “pentito”, but for his relatives and friends.

Buscetta's decision to cooperate cracked another solid wall traditionally seen as an impenetrable defense against authorities' attacks: the “omertà” (code of silence). While Buscetta may have been Italy’s very first Mafia informant, he was followed by numerous others. The resulting damage to La Cosa Nostra and other criminal syndicates has had serious repercussions for the Mafia even today.

Buscetta revealed crucial information to the prosecutors, not only for the maxi-trial itself but also for understanding the complex system of La Cosa Nostra, its modus operandi, structure and chain of command in Italy and the United States. His revelations would later form the basis of the work by Prosecuting Magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino in the fight against the Sicilian Mafia.

The trial brought the La Cosa Nostra to its knees. But it could still fight back.

“We must declare war on the State so as to make peace afterwards,” said Toto Riina, the Sicilian Mafia’s boss of bosses, in 1992 according to the prosecutor’s report. “In the future we cannot allow politicians to turn their back on us again,” stated boss Leoluca Bagarella in a wiretap. The strategy of La Cosa Nostra was to confront the Italian state with an unprecedented wave of violence and threats. On their black list were politicians and public officials: if the State did not grant La Cosa Nostra a number of requests, blood would flow.

And it did.

The “strategy of violence” Prosecutors Giovanni Falcone (left) and Paolo Borsellino (right), friends and colleagues, killed in 1992.

Prosecutors Giovanni Falcone (left) and Paolo Borsellino (right), friends and colleagues, killed in 1992.

Totò Riina, who had emerged as the undisputed boss of La Cosa Nostra in the aftermath of the 1980’s Second Mafia War, outlined numerous demands to state officials. Among them, a revision of the maxi-trial sentences; a change in Italian law to restore certain rights for inmates like Mafia affiliates and murderers; a revision of the “Rognoni-La Torre law” that made it illegal to have a Mafia affiliation and many others, according to Italian weekly L'Espresso.

The Palermo prosecutors believe the very survival of the Mafia was at stake. The requests were meant to give new impetus to La Cosa Nostra and form the backbone of a new relation with the State, building a new and prosperous future for the Sicilian Mafia.

At the same time, prosecutors say, Riina launched the stick that went with his carrot -- a campaign of murders. Dozens of policemen, state officials, politicians, judges, journalists and lawyers were killed in reprisal and as part of a bloody strategy aimed at forcing the state to accept La Cosa Nostra’s demands.

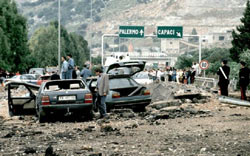

On May 23 1992, Prosecuting Magistrate Giovanni Falcone together with his wife and three escort agents were blown up on a motorway near Palermo. Almost two months later, a bomb in Palermo claimed the life of Falcone's close friend and colleague, Magistrate Paolo Borsellino and his six agents. It didn’t stop there. On May 27, 1993, a car bombing in the centre of Florence killed five people. Two months later, on July 27, two bombings in Milan and Rome claimed another six victims. The violence shocked and outraged the nation.

“These killings certainly influenced the beginning of what we describe as the Second Italian Republic, and in between we have discovered – which is the issue in this trial – that there were parts of the State who were negotiating with criminal organizations, with the Mafia, about a new deal for cohabitation”, former Deputy Prosecutor of Palermo Antonio Ingroia told Euronews last October.

Riina was arrested in January 1993 after being wanted for 24 years. He partially rescinded the strategy that had been in effect for several years but, according to Ingroia and his colleagues, it did not stop the mob’s negotiations with the state.

“La trattativa” The scene after a highway bomb took the life of prosecutor Giovanni Falcone, his wife and three escort agents.

The scene after a highway bomb took the life of prosecutor Giovanni Falcone, his wife and three escort agents.

The trial of the bombings that shook Italy in 1993 ended in March 2012. One hundred pages of the 500-page sentence report focus on the reasons behind the bombings. One paragraph reads:

“A negotiation [between State and Mafia,] based on a do ut des undoubtedly took place.” (Do ut des is Latin for the equivalent of “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.”)

The people who allegedly made the deal now must face the court. Five Mafia bosses (Totò Riina, his replacement as mob boss Bernardo Provenzano, Leoluca Bagarella, Giovanni Brusca and Antonino Cinà), two former ministers (Calogero Mannino and Nicola Mancino), a senator (Marcello Dell'Utri), three former Carabinieri (Generals Mario Mori, Antonio Subranni and Colonel Giuseppe De Donno) and former Palermo mayor son's Massimo Ciancimino are now defendants in the trial on the State-Mafia agreement.

The criminal charge against Mafia bosses Riina, Provenzano, Bagarella, Brusca and Cinà is “violence or threat against a state institution”. The prosecutors believe that the extortion came through the murders, bombings and other violent acts carried out against institutions and politicians to force the government to agree to their requests.

State officials Mannino, Mori, Subranni, Dell'Utri and De Donno are also charged with violence agains the state. The prosecutors believe they deliberately helped deliver Mafia threats, acting as mediators but in reality extorting concessions from the state. Former minister Mancino is charged with “false testimony”, whereas Massimo Ciancimino faces charges of making false statements.

According to the prosecutors, the negotiators’ final targets were former Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti (who died on 6 May this year, and was in office from 1989 to 1992), and his Minister for Special Interventions in the South, Calogero Mannino. Only they and President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro had the power to grant La Cosa Nostra's requests, say the prosecutors. The state apparently compromised, and in 1993 around 300 Mafia members gained improved prison conditions, while Riina was removed from solitary confinement.

However, the prosecutors say, La Cosa Nostra was not satisified. Their ultimate aim was to establish permanent relations with the political elite, believing this necessary for long term prosperity. They also wanted access to contracts and tenders, and impunity. They got their chance when Andreotti’s successor, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi's government, was replaced by a new political era: Silvio Berlusconi had come to power.

The prosecutors believe that the negotiation was finally resolved in 1994 when La Cosa Nostra managed to hand over their wish list to recently elected Prime Minister Berlusconi. Through the crucial mediation of now former senator Marcello Dell'Utri – a close collaborator of Berlusconi – Mafia bosses Giovanni Brusca and Leoluca Bagarella received the necessary guarantees that a pact was finally reached, the prosecutors say. Dell’Utri was eventually sentenced to seven years in prison in March of this year by the lower court of Palermo for the crime of “external participation in Mafia affiliation”.

More disclosures are likely to come out of La Trattativa as the trial progresses but justice will not be swift.

“It will likely be a long trial,” Ingroia told the daily newspaper, La Repubblica last year. “We need to be patient.”