The AUP forces would turn security checkpoints into toll booths, demanding cash from anyone who wanted to pass. They moonlighted as private security officers for civilians.

"Despite our best efforts, we could not convince the AUP that this was unethical," Ray said. "When we addressed and condemned it, they merely moved their operations out of view.”

Tom Coughran is a Green Beret major in the US Army and a veteran of multiple deployments to Afghanistan. He has mentored and molded the Afghan army's commandos, and he has observed the training of thousands of young Afghans to become professional officers in the Afghan National Police, or ALP. Coughran has watched as provincial leaders treated the valuable ALP slots as bartering tokens to curry favor with tribal figures and warlords.

"These ALP jobs, they're like baseball cards," he says. "They're a form of currency, they trade them."

The extortion and haggling over security forces described by Ray and Coughran is typical of the everyday corruption that ailsAfghanistan. But that type of commonplace, low-level corruption is not the war-torn nation’s biggest problem.

Coughran explains, "Is it corrupt? Yes. Is it in the grey area? Yes. But is it really degrading to security and stability in Afghanistan? That depends on where it's happening, depends on the area, so there's an example of corruption that's not right by our standards but right by Afghan standards."

With 2014 and the planned drawdown of NATO forces fast approaching, decisions made in coming months will determine the legacy of America's longest war. Some voices are calling for an abrupt pullout while others are calling for the eradication of all corruption, but those on the ground realize that a healthy Afghanistan requires a different approach.

A Way of Life An Afghan police officer stands alongside a coalition soldier in Daykundi province.

An Afghan police officer stands alongside a coalition soldier in Daykundi province.

After more than a decade of fighting, war-weary nations are edging towards a complete pullout from Afghanistan, raising the risk that all progress made by coalition forces will evaporate without a continued international presence.

Sending young men and women to fight in a remote country is becoming ever less appealing to countries with troops in Afghanistan, and public support for the war is slipping away in the United States and its allies. Progress in the developing nation is difficult to measure, while reports of misspent funds, difficulty in training Afghan forces, and rampant corruption are powerful reasons for the US Congress and European parliaments to end the war efforts.

Capt. Ray says that the Western concept of "corruption" does not apply in Afghanistan, where "most Afghans see it as 'survival.'"

Bribery in Afghanistan is often the cost of doing business. Local leaders say they are only able to conduct dealings by giving and taking on the side. Sometimes it's money, sometimes it's jobs, sometimes it's as specific as ammunition, but it's often necessary to grease the wheels to get anything done.

Coughran explains that "in many ways the corruption challenges the peace, but in many other ways the corruption is what's holding this country together." In fact, low-level corruption may benefit the country, he thinks. Local leaders skimming off the top contribute to a more stable Afghanistan, because "they're willing to put the thumbscrews down on the people and tamp down the violence in their areas to make sure that they continue to benefit from the corruption," says Coughran, who believes that tackling low-level corruption is a fool's errand.

Instead of trying to prosecute every police officer who demands a bribe, many analysts and people serving in Afghanistan say that it makes more sense to focus on uprooting the high-level, large-scale corruption that causes far more damage to the country.

In 2012, investigations revealed that the heads of Kabul Bank, the institution paying the salaries of the Afghan military and police, were lining their pockets with hundreds of millions of dollars they funneled to Dubai. The scandal infuriated donors around the world, not only because Kabul Bank was egregious in scale, but because aid money was leaving the country.

And yet not everyone agrees that the major focus should be on high-level corruption. US Maj. Gen. Rick Waddell, in charge of a transparency task force, told NPR that corruption should be tackled from bottom to top.

"We work with good Afghans at all levels of the government," the general said. "What we tell them is let's go after the ones that we can, you go after lower-hanging fruit to make a difference."

But Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington defense analyst Anthony Cordesman counters, "The real problem with the low-hanging fruit is, why low hanging?"

Cordesman believes that the easy targets are either too insignificant to matter or are being hung out to dry by their opponents, and either way it's a waste of resources to investigate them.

Playing the Long Game Head of SIGAR John Sopko

Head of SIGAR John Sopko

For over a year now, John Sopko’s job has been to root out waste, fraud and corruption in aid programs to Afghanistan. Since mid-2012, as head of the Office of the Special Inspector General for the Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR), he has examined programs involving $US10.6 billion in aid money.

Of that, a SIGAR report says, about two-thirds is “at risk of waste, fraud and abuse.”

Sopko believes in going after the big targets. "I’m into accountability," he says. And while he believes that "embarrassing people works," he also says that if it doesn’t, "putting people in jail also works—it gets their attention."

Sopko understands the value of public relations. He says public support is essential to getting things done, and his office "aggressively flags [reports] to reporters," according to The New York Times. "If you want to make a change, you need to get to the American people," says Sopko.

Sopko's aggressive inspections have drawn ire from the State Department and USAID. One senior American embassy official told the Times that drawing so much attention to corruption was counterproductive. "It starts to generate an incomplete and unjustified loss of credibility and trust in what the international community is trying to do on the development side."

Austin Long, a former analyst and adviser to the military in Afghanistan, says that perception is crucial. The future of the mission is dependent on perceptions of progress, and corruption is a popular metric for evaluating progress. If after a few years no significant gains seem to be made, the US Congress and European parliaments will be thinking "we are just pissing money down a rat hole," Long says.

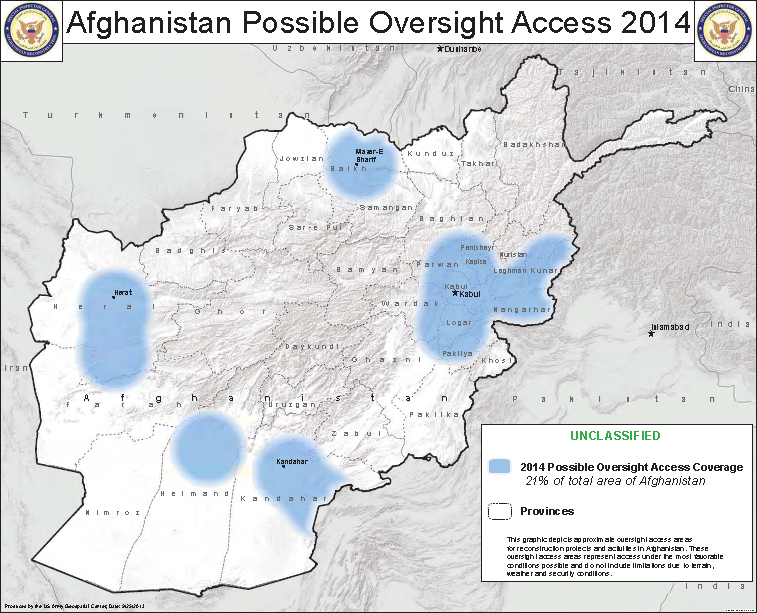

Tracking the money is one way to measure whether corruption is hurting Afghanistan. If stolen funds are sent out of the country, as was the case with Kabul Bank, the long-term impact could be severe. Money that is stolen and secreted in offshore accounts is money that is not used for better roads, schools, hospitals or other long-term investments in Afghanistan’s future. "Oversight bubbles" are expected to cover only 20% of Afghanistan in 2014.

"Oversight bubbles" are expected to cover only 20% of Afghanistan in 2014.

Such large-scale acts of corruption threaten stability not only because of the immediate impact of the crimes, but because they infuriate the foreign nations writing checks.

"Whatever investment the US has made in Afghanistan to date will only survive if there's continued investment in the future," says Long, who believes progress in Iraq evaporated after the US troops left in 2011. He says donors will stop supporting Afghanistan if they believe their money is being stolen, abandoning the country to crime, corruption, and lingering insurgency.

That is, ideally, where Inspector-General Sopko comes in. But Sopko believes his hands are being tied as coalition forces pack up and go home, reducing the area in which he can work. Military planners divide Afghanistan into districts based on access to advanced medical facilities—each hospital is surrounded by a one-hour "bubble", meaning anyone injured within that area is less than an hour’s travel away from treatment.

Sopko and his inspectors are only supposed to work within these "oversight bubbles." But as the troops go home and one bubble after another disappears, they have less and less area to work in. The protected area is projected to be only 20 percent of the country by 2014.

Legacy on a Deadline Afghan President Hamid Karzai stands before the Loya Jirga.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai stands before the Loya Jirga.

Public opinion in the United States is increasingly against the war, with the percentage of Americans who call it a mistake ticking closer to a majority in nearly every Gallup poll since the 2001 invasion. At the onset, less than one in 10 Americans were against the war. That portion has climbed up to half of all Americans in 2013.

Against this backdrop an Afghan grand council of elders known as the loya jirga convened in November to debate the future of international forces. While Afghan opinion is not unanimous on allowing a continued international presence, a deal is expected.

Critics have slammed the loya jirga as merely a front for Afghan President Hamid Karzai, saying that an agreement with Washington is inevitable; the council is seen as merely a smokescreen for the Afghan president to avoid appearing as an American puppet. A healthy Afghanistan needs foreign money, and Karzai knows this.

In mid-November Karzai announced that a tentative forces agreement between Washington and Kabul had been reached albeit with several contentious factors still up in the air, but as of the end of November Karzai has refused to sign off despite pressure from both the council and Washington.

On the other end of the negotiations, the intentions of foreign coalition nations are more uncertain. The war in Afghanistan is continuing to lose support, while administrations in America and Europe experience the usual turnover and fluctuations in political will.

On the other end of the negotiations, the intentions of foreign coalition nations are more uncertain. The war in Afghanistan is continuing to lose support, while administrations in America and Europe experience the usual turnover and fluctuations in political will.

Current plans would leave 8,000 to 10,000 international troops in Afghanistan after the 2014 drawdown, but guesses vary as to how long those troops would stay. A pullout by US forces, who make up the bulk of the troops, would be mirrored by all other coalition nations, leaving Afghanistan alone to deal with insurgency and crime.