When Erik Súñiga died in U.S. custody in April, he left a rich religious and political legacy in the Guatemalan town where he founded an evangelical church, and served as mayor for over a decade.

He also left behind a property empire that was most likely built with drug money. Some of that cash appears to have been laundered through his religious and political network.

That is one of the findings of a cross border investigation by 12 media organizations from nine countries, coordinated by Columbia Journalism Investigations and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), OCCRP’s regional partner in Latin America, into church-related money laundering across the Americas.

The phenomenon is widespread, as religious organizations often escape scrutiny due to their respected role within communities and the lack of regulation governing their affairs, experts say. In a number of countries, this includes tax exemptions.

“Over the years, religious institutions have been repeatedly used ... to launder money,” said Mark Califano, a former assistant U.S. attorney and chief legal officer at Nardello & Co, a global investigative firm. “And their special and protected place in most countries and societies has allowed that to happen.”

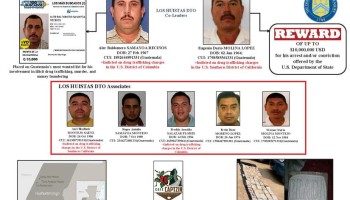

Súñiga turned himself in to U.S. Drug Enforcement agents in Guatemala in December 2019 and was extradited to Texas. The Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control identified him and his organization as “significant foreign narcotics traffickers” and froze his assets in the U.S.

He was reportedly suffering from pancreatic cancer and died before facing trial on drug trafficking charges.

American officials also probed Súñiga's finances, but did not charge him with money laundering,as they didn’t find strong evidence of illicit transactions occurring within the U.S., said a source with knowledge of the investigation.

“Money laundering charges require more direct proof of financial transactions that touched the United States,” the person said in an email.

In Guatemala, reporters scoured court and land records to uncover evidence indicating that Súñiga probably laundered at least US$1.4 million through a scheme in which a fellow pastor bought properties and then resold them to the municipality Súñiga headed.

A municipal accord passed shortly after Súñiga came into office allowed him to grant at least three pieces of public land to people linked to convicted drug trafficker Juan Alberto Ortiz López, also known as Chamale. Ortiz was reported to have ties to Mexico’s powerful Sinaloa cartel.

A 2013 document from the Guatemalan authorities identified a mayor in San Marcos, the department that includes Ayutla, as someone “believed to be involved in drug trafficking.” A 2015 court document revealed that authorities wanted to strip the immunity Súñiga held as mayor, because he was suspected of money laundering. The court recommended he be prosecuted for money laundering, but charges were never brought against him. Súñiga remained in office another five years, 12 in total, until he surrendered to U.S. authorities in December 2019.

While other churches have also been accused of laundering the proceeds of drug sales, the cross-border investigation found that cash came from other sources too.

Biofuel Fraud

Jacob Kingston, a member of a Mormon sect primarily based in Utah, was involved in a $1 billion renewable fuel tax credit fraud scheme. Kingston headed of a company called Washakie Renewable Energy, which falsely claimed to be selling the cleaner fuel in order to access tax credits.

Kingston and his wife, mother, and brother all pleaded guilty to crimes relating to the biofuel scam, including money laundering and mail fraud. They cooperated with U.S. prosecutors, who brought charges against their accomplice Lev Dermen, a California businessman. Dermen was convicted in March, and he and the Kingstons are awaiting sentencing for the scheme that ran from 2010 to 2016.

The money trail began with Washakie, which would sell biodiesel to a company controlled by a co-conspirator. The same fuel would then be moved through another company the conspirator either had an interest in or controlled, giving the impression that it was being bought and sold on the open market. That company would resell the fuel as a biodiesel mixture to Washakie, which then claimed it qualified for tax credits.

“To further create the appearance they were buying and selling qualifying fuel, the co-conspirators cycled more than $3 billion through multiple bank accounts,” the U.S. Justice Department said in a March 16 statement.

The fuel was shipped around the U.S. and internationally. Kingston and Dermen “doctored production and transportation records” in order to claim renewable fuel tax credits, according to the Justice Department.

Washakie filed fraudulent Internal Revenue Service forms, and received checks in the mail from the U.S. Treasury Department. Dermen and the Kingstons would use various methods to hide the money, including depositing some in Turkish bank accounts, buying luxury vehicles, and purchasing real estate. Some money was laundered through the Kingstons’ Latter Day Church of Christ.

Prosecutors found that the church ended up with $194,040 out of over $71.6 million in payments from the Treasury Department, which passed through the church on its way through various companies and finally back to Washakie.

According to a separate complaint filed last year in a district court in Utah, the church’s doctrine includes a tenet called “Bleeding the Beast,” which justifies fraudulent conduct against outsiders to benefit the congregation.

A church spokesperson denied the practice, saying: “These allegations by a small number of ex-members are absolutely false.”

The biofuel scandal has not affected the church’s eligibility to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions.

“It’s this untouchability aspect that we have unintentionally crafted in the U.S. through several different mechanisms,” said Marci A. Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies religion.

The reason “religious groups are so convenient for money laundering, parking proceeds, is that for federal tax files you don’t have to specify where your money came from and what you do with it,” said Hamilton. “There’s this black box quality to their public space.”

Further Investigation

The scope of the investigation shows how widespread across the Americas allegations of church involvement in money laundering are. Here are some of the cases reporters examined:

In Mexico, reporters looked into the case of Naasón Joaquín García, who heads a church called La Luz del Mundo. Authorities in California arrested Joaquín on charges of raping a minor and human trafficking, He is also under investigation in Mexico for laundering money. Members of his congregation allegedly hid cash on their bodies or smuggled it inside luggage into Mexico, where the church is connected to 51 properties. Naasón, his family, the church and a charity incorporated by one of his sisters are also linked to 31 properties in the U.S. estimated to be worth nearly $20 million. The country’s Financial Intelligence Unit is probing suspicious transfers of cash to accounts in Hong Kong, Bolivia, Poland, and the United States. Mexico earlier this year froze about $19.4 million held in accounts connected to the church, according to local media reports.

A pastor from the Dominican Republic, Jorge Mercedes Cedeño, pleaded guilty before a Colombian court to belonging to a criminal organization called the Urabeños (now known as the Gulf Clan), which is one of Colombia’s most powerful drug cartels. According to his 2015 conviction, he managed a “good part” of their finances and bought property for them. The ruling also established that he wired money from the organization to his home country disguised as donations from parishioners. Cedeño had been caught in Colombia a year earlier carrying a large amount of cash.

Reporters discovered that an Argentinian prosecutor is investigating the country’s branch of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, a global behemoth that began in Brazil. Authorities detected suspiciously large cash deposits into church accounts between 2010 and 2014.

The case in Argentina illustrates how churches can be vulnerable to being co-opted for money laundering, according to Emilio Guerberoff, a prosecutor with the country’s Economic Crimes Jurisdiction.

“By receiving anonymous donations through tithes – whose origin may not be explained – churches become the perfect money laundering machine,” said Guerberoff, who is taking part in a probe.

"There may be a clash of interests between freedom of religious worship and the prevention of money laundering.”

Stories by Columbia Journalism Investigations (U.S.), Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism, OCCRP, Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad (México), Nómada (Guatemala), Canal 13 Noticias (Costa Rica), IDL-Reporteros (Perú), Infobae (Argentina), Agência Pública (Brazil), Folha de São Paulo (Brazil), La Diaria (Uruguay), El Tiempo (Colombia)