For about 12 kilometers west from the Namibian town of Katima Mulilo, along an old smugglers’ track that runs along the Zambian border, hundreds of teak and rosewood trees lie grey and dead. Their felled trunks ooze red resin, much like the blood of the elephants that once inhabited this stretch of state forest -- before the poachers came.

And just like with the demand for ivory, it’s a Chinese trend -- the current craze for redwood or hongmu furniture as a status symbol -- that has ignited a logging rush that’s devastating sub-Saharan Africa’s remaining hardwood forests.

Here in Caprivi State Forest, the trees are being cut down by crews working for Xuecheng Hou, a controversial Chinese businessman with prior criminal convictions, who, along with his associates, has been involved in the illegal wildlife products trade. He is currently facing several criminal charges in Namibia for alleged dealing in wildlife contraband. When the hardwood teak and rosewood trees are cut down, the local Mafwe tribe and the Namibian government will get a few dollars per tree, and the wood will sell for thousands in China.

Meanwhile, rather than stopping the wholesale deforestation of a national forest, the government has left the land in a vague legal limbo that has made it easier for the plunder to continue. The Director of Forestry gave vague and often contradictory answers to reporters, and no one seems committed to stop the clearcutting.

Bloodwood

A loud crack sent a shudder through the Caprivi State Forest, heralding the fall of another giant.

Three days of covert observation by a journalist from Oxpeckers, an OCCRP partner that specializes in investigating environmental crime, established the pattern: Every morning, the Chinese foreman would drop the logging teams off deep in the state forest, several kilometers away from Katima and Liselo Farms, where, according to their contract, they were supposedly clearing an area for the Green Scheme, a crop growing program designed to spur food production.

Carrying water and fuel, the men would fan out, looking for the densest copses of rosewood and teak, where they cut down the oldest and biggest trees before dismembering them to dry the wood quicker. The oldest ones oozed the deepest red resin.

Later, a heavy front-end loader would be brought in to rip open a path for a machine that lifts the logs onto a rickety trailer and moves them to a camp near an electricity sub-station where several hundred trees had already been piled.

Saw-men at work cutting trees in the Caprivi State Forest. (Caption: John Grobler)

Saw-men at work cutting trees in the Caprivi State Forest. (Caption: John Grobler)

The region’s agricultural lands have long been denuded of the slow-growing African rosewood and teak trees. But a number still remain in areas under state control. That’s where the crews have now moved in to harvest them.

Approached by a reporter a few days later at a service station and informed that his teams were harvesting illegally, the crew’s Chinese foreman, Weichao Li, became visibly angry and refused to discuss their work. “Me no talk to you, only to state.”

“You no come here again, you see [what happens],” he said.

It’s back-breaking and dangerous work, six days a week, for good pay: N$100 (about US $7.50) per tree, said one of the saw-men. “My best total for one day of cutting was 60 (trees),” he said.

With six two-man teams at work day after day, it quickly adds up to serious deforestation. Instead of clearing only 1,650 hectares within the two designated farm areas, the crews have felled trees over an area estimated to be four times larger in the adjoining state forest.

Already, an estimated 8000 hectares, or 5.4 percent of the Caprivi State Forest, has been felled, according to an analysis of satellite photos. The forest had been untouched since at least 1968, when the apartheid South African government, which then administered Namibia, ordered the local people out of the area, according to former Caprivi game warden Jo Tagg.

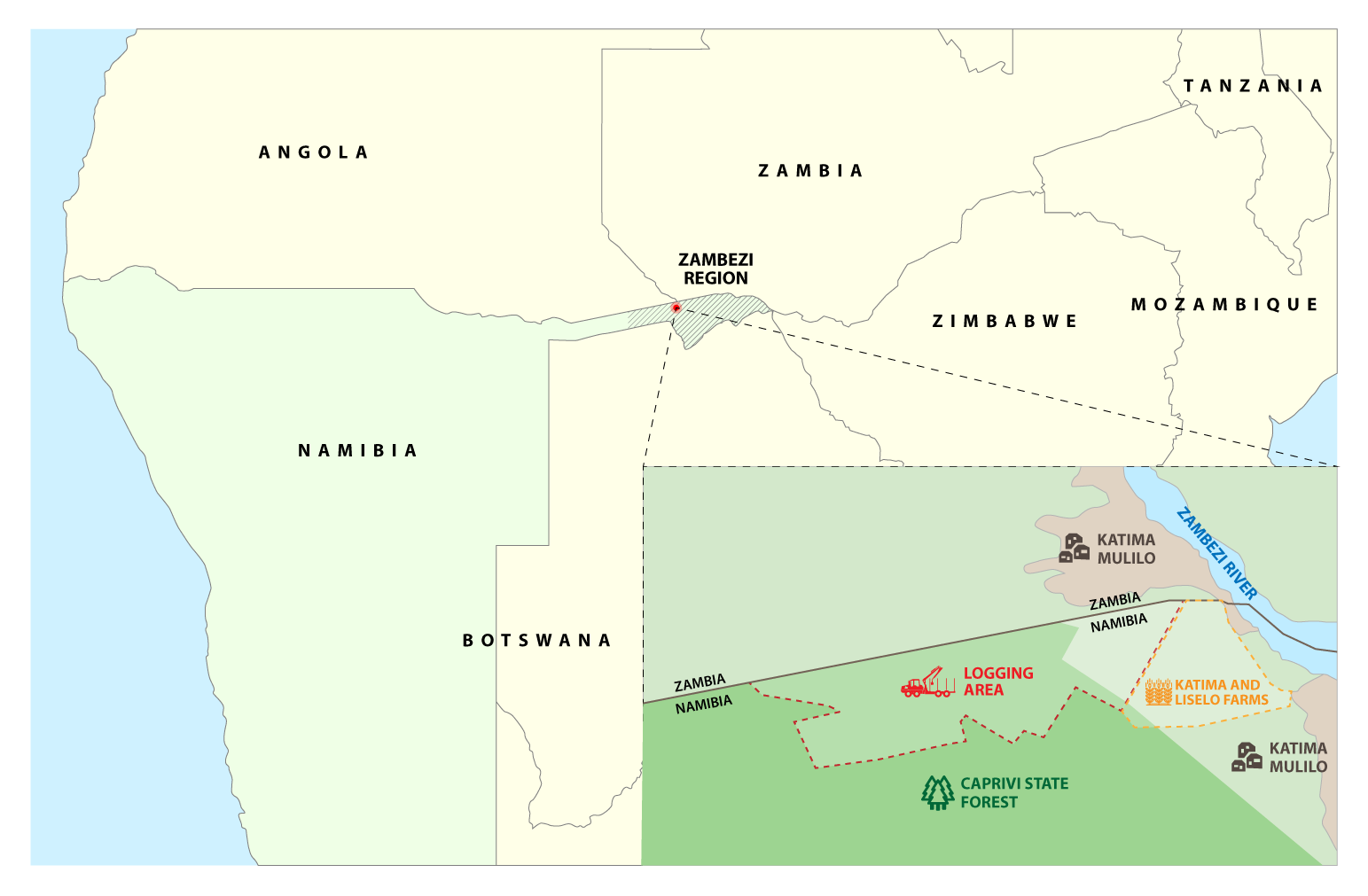

An analysis of satellite images shows where loggers crossed deep into the Caprivi State Forest. The park is in Namibia's Zambezi region. (Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic)The Caprivi State Forest lies in the Zambezi region, formerly known as the Caprivi Strip, a narrow extension of Namibia that juts like a handle 280 miles to the east. The area remains sparsely populated, rich in wildlife, and is an important migration corridor for animals in the surrounding countries. The region’s rosewood forests are particularly susceptible to destruction because they grow very slowly -- only about 3 mm in diameter per year. Many of the trees being cut are over 150 years old.

An analysis of satellite images shows where loggers crossed deep into the Caprivi State Forest. The park is in Namibia's Zambezi region. (Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic)The Caprivi State Forest lies in the Zambezi region, formerly known as the Caprivi Strip, a narrow extension of Namibia that juts like a handle 280 miles to the east. The area remains sparsely populated, rich in wildlife, and is an important migration corridor for animals in the surrounding countries. The region’s rosewood forests are particularly susceptible to destruction because they grow very slowly -- only about 3 mm in diameter per year. Many of the trees being cut are over 150 years old.

A Legal Limbo

Like Namibia’s five other state forests, Caprivi was supposed to be protected from this kind of commercial logging. But an investigation by Oxpeckers reveals how the system has failed.

The forest is stuck in a legal limbo that has made the illegal exploitation much easier. Caprivi State Forest was slated to be one of the six national forests, according to the Forest Act of 2001. Article 13 of the act prescribes how state forests of national importance for their biological diversity are to be declared by the Minister of Environment and Tourism. In conjunction with the Ministry of Land Reform, the Minister is supposed to issue a notice in the Government Gazette.

But no such Proclamation or Ministerial Notice appears to have ever been issued since 2001 for the Caprivi State Forest or any of the other state or community-controlled forests. Willem Prinsloo of the Legal Assistance Center (LAC), a legal rights organization in Windhoek that also tracks land use issues, said neither he nor anyone he has spoken to have seen such an announcement.

Also complicating the issue is a claim to some parts of the area by the indigenous Mafwe tribe.

The lack of legal clarity has left a loophole that the Chinese wildcat loggers may now be exploiting, using the Zambezi region’s Green Scheme as a means to bypass forest protection regulations.

As part of the scheme, a bush-clearing contract was awarded to MK Capital Investment and Okatombo Investment, a joint venture of two local Namibian companies. The work was then sub-contracted to another company called Uundenge Investments, who entered a contract with Xuecheng Hou’s New Force Logistics to allow the latter to cut any trees with a diameter beyond 15 cm after they had cleared the bush away. (See: Illegal Tender)

Except the Chinese largely ignored the fact that they were only to fell trees on the contracted area, which includes the Katima and Liselo farms abutting the Caprivi State Forest. Instead, they started felling trees in the adjacent forest, where they were much more numerous.

The Forest Steward

Reporters talked to Director of Forestry, Joseph Hailwa, who has run the directorate for 15 years. As secretary of the Forestry Council, he is the man responsible for protecting forests and enacting the Forest Act. But since he has been in office, he has never designated Caprivi State Forest -- or any of the other five state forests -- as protected land.

Director of Forestry Joseph Hailwa. (Credit: John Grobler) In two separate meetings with a reporter on behalf of OCCRP, at the head office of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF) in Windhoek, Hailwa gave vague answers, contradicted himself, or made statements that turned out to be untrue.

Director of Forestry Joseph Hailwa. (Credit: John Grobler) In two separate meetings with a reporter on behalf of OCCRP, at the head office of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF) in Windhoek, Hailwa gave vague answers, contradicted himself, or made statements that turned out to be untrue.

Pressed to explain why none of the designated forests had never been declared as envisioned by the Act, he angrily said that “Caprivi State Forest was declared by the (apartheid-era) Pretoria government!” However, there is no evidence this is true.

Hailwa’s involvement has been questionable since Feb. 2, when forest wardens from Katima Mulilo on a routine patrol caught the Chinese-run groups cutting within Caprivi State Forest, west of the Liselo farm boundary. They confiscated the loggers’ chainsaws and logged the incident on their internal GIS system.

Although he initially denied it, Hailwa admitted in a second interview that he had ordered the equipment be returned to the Chinese logging group. Hailwa explained that the confiscation was a misunderstanding because his officials had been unaware that the Chinese crew was entitled to harvest trees under the Green Scheme project.

Hailwa could not explain the scope of the Green Scheme, saying he had no maps of the project. He initially said the project encompassed 4,000 hectares, but then in the second interview insisted he had said 2,000 hectares (the actual amount is 1,650 hectares).

He also insisted that no harvesting permits were required because the Chinese crews were operating under the tender to clear land for the Green Scheme. However, the tender itself is questionable because only Liselo Farm had to be cleared, as Katima Farm was already cleared prior to 1990 for a failed scheme to produce bio-fuel.

“The tender is the harvesting permit,” Hailwa insisted.

According to Forestry Regulations promulgated in 2015, no forest products can be harvested without a harvesting license and transport permit. Hailwa confirmed that only one permit had been issued for Katima farm. According to a Directorate of Forestry brochure, a permit is required for any tree cutting or harvesting of wood in an area greater than 15 hectares per year.

“If I have proof that they are cutting outside the area they’re supposed to stick to, then I will order that wood confiscated,” Hailwa said in his first interview with reporters.

Later he said of the loggers, “my staff said they were within the legal area.” But he had also prohibited his staff from speaking to the press, saying any queries could only be answered directly by him.

In the second interview, Hailwa said the directorate had ordered the logging to be halted and investigated. But a week after the interview, on August 11, Xuecheng Hou’s trucks were allowed to leave for the port of Walvis Bay with loaded containers of wood after paying an “admission of guilt fine,” said Martin Dumeni, director of investigations at the customs service, which is investigating the logging.

Hailwa claimed to know nothing of the illegal logging within the Caprivi State Forest, but on July 14, witnesses observed state forestry staff in the Chinese foreman’s vehicle, deep inside the forest, counting felled trees and marking the choice logs as Hou’s.

Hailwa said that forestry staff have been tracking the logging in the state forest because “this wood should not be for mahala [nothing].” But Namibia is not getting a good deal. He admitted the Chinese were paying only N$200 (US$ 15) per tree. A tree yields on average six cubic meters of timber. On the Chinese Alibaba website, such timber sells for between $400 and $2,100 per cubic meter.

At another point, Hailwa argued that the land in question was really under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Land Reform, the Regional Land Board, and the local Mafwe traditional authority.

Trucks loaded with hardwood timber from the Democratic Republic of Congo parked at Katima Mulilo. (Credit: John Grobler)

Trucks loaded with hardwood timber from the Democratic Republic of Congo parked at Katima Mulilo. (Credit: John Grobler)

In an interview with The Namibian on July 10, senior Mafwe advisor Elias Mueze told people to mind their own business. He argued that the traditional authority supported the harvest and had signed an agreement for 1,600 hectares for the Green Scheme project.

The Mafwe traditional authority was receiving some income from the logging which was being used to upgrade their offices, Mueze told The Namibian.

“Therefore, the government has all the right to cut down all those trees or to allow any company that has won the tender to cut down those trees from that area,” he was quoted as saying.

But what isn’t clear is why Hailwa considers the land now being harvested to be outside the park. Pressed to produce a map to show the boundaries of the area to be de-bushed, Hailwa could not do so or point to anyone in his department who had that information. This was the responsibility of the Directorate of Agricultural Production, Extension and Engineering Services, he said.

Hailwa also did not have either the map or coordinates used by the Chinese loggers now, and therefore could not tell whether they were working within the designated area. “Bring me the hard evidence, and I will take the wood from the trees cut outside [the construction area],” he said.

A Google Earth map, marked up with GPS data showing how far the Chinese loggers were working outside of the designated area, was sent to Hailwa’s office after the first interview.

The blurring of both the legal boundaries and official lines of responsibility within the MAWF has facilitated a contract creep from 1,650 hectares to over 8,000 hectares – and likely much more.

The threat to the state forest may be even more dire. Sources in the Directorate of Forestry told reporters that there were plans to dish out various tracts of land amounting to 44,000 hectares to various private and public entities, all within the 146,100-hectare Caprivi State Forest.

Another controversial plan, pushed by rising politician Armas Amukwiyu of the ruling SWAPO party and Chinese interests, will turn 10,000 hectares of the state forest into a tobacco farm over objections from local environmental NGOs and community leaders.

Hailwa acknowledged these projects, but could not provide any published notice of revocation of the forest land status in the Government Gazette, as required by Article 17 of the Forest Act.

The main man in the Chinese led operation, Hou, could not be reached for comment, but in a previous interview, he denied that he was involved in hardwood harvesting and said his company, New Force Logistics, only did the transport.

Hou has a long track record of involvement in criminal cases in Namibia, including being accused of possessing and dealing in illegal ivory, stolen animals skins, and other crimes, but he has yet to face trial on any of these charges.

A member of Hou’s group, Otjiwarongo shop-keeper Wang Hui and three other Chinese citizens, were sentenced to 14 years in jail by the Windhoek Regional Court in September last year for the attempted smuggling of 14 rhino horns in March 2014.

The Illegal Tender

(Return to main story)

The land-clearing tender which allowed the crews to cut the trees is highly problematic. To understand why, one has to go back to July 2016, when two tenders – one for de-bushing irrigation fields, the other to fence in the area – were issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry.

Forty-seven bids, ranging from N$4.8 million ($335,000) to an astronomical N$441.7 million ($30.8 million), were received for the de-bushing contract, and 46 offers ranging from N$6 million ($418,000) to N$43.6 million ($3 million) for the fencing job.

Both tenders were specifically written for black economic empowerment “tenderpreneurs,” a South African term for a person who uses their political connections to secure government contracts. For the de-bushing contract, 51 percent of the company had be Namibian-owned. For the contract to fence the area in, 100 percent had to be Namibian-owned. In both tenders, 30 percent of the shareholders had to be from previously disadvantaged groups, according to the Tender Bulletin, which monitors all public tenders.

The de-bushing tender was awarded to MK Capital and Okatombo Investments by the Tender Board and confirmed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF). That joint venture then sub-contracted the job to Uundenge Investments, which is owned by local businessman Laban Kandume.

However, about two months after both tenders closed on July 19, an engineer from the MAWF’s Directorate Agricultural Production Extension and Engineering Services, applied for a tender exemption from the Tender Board for the very same de-bushing tender.

The letter, dated Sept. 21, stresses the project’s national importance as a reason for the tender to be declared exempt from the normal public bidding process -- even though the process had already taken place.

“This project should necessarily be treated as one of the priority projects aligned to the Harambee Prosperity Plan (HPP), contributing to enhanced food security and hunger eradication in Namibia,” the unsigned letter said.

Harambee, a Swahili word related to charity, is the name given by President Hage Geingob to his poverty reduction policies, which call for accelerating certain projects. It is not clear whether this exemption was granted by the Tender Board -- its officials referred all queries back to the MAWF.

To add more to the confusion, the letter asked for the de-bushing contract to be accelerated but referenced the separate fencing contract.

Neither MK Capital nor Okatombo Investments had entered any bid for the second tender -- erecting a fence around the project area -- but they were awarded the N$20 million ($1.4 million) contract anyway, bringing their total contract value to about N$46 million ($3.2 million), as they later confirmed in a meeting at a Windhoek restaurant on Aug. 10.

In this meeting, Kandume explained that he was invited by Matty Kamati, who introduced himself as the owner of MK Capital, and was present in the meeting, to become involved in this project, but insisted they had nothing to do with the wood business and intended to end the contract with Hou although they could offer no proof.

Why the MAWF would request a tender exemption for this de-bushing contract and then award the fencing contract to a company that did not enter a bid is not clear. The author of the letter was in the field and could not be reached for comment, a person answering his office phone said.

Kandume did not respond to phone calls or texts messages to clarify why neither MK Capital or Okatombo Investments nor their joint venture had entered any bid for the fencing contract, but somehow still obtained the job under a questionable tender exemption for the other contract.

This story was reported in collaboration with Oxpeckers. It is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a partnership between OCCRP and Transparency International. For more information, click here.