While the citizens of the country live in poverty, President Obiang and his family have enriched themselves using an intricate network of corruption.

Obiang’s corruption has come under the glare of media and governments. Authorities in several countries are tightening their grip on Obiang and his family and their sophisticated network for laundering embezzled funds. French, Swiss and Spanish authorities have filed cases to recover assets tied to the president and his relatives.

But the Obiangs have not worked alone. Reporters for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and its Lithuanian partner, 15min, found that Obiang and his family were assisted by at least two partners in Eastern Europe. The Eastern European-connected deals include owning and managing a fleet of cargo ships as well as constructing and managing a shipyard in the African country.

Power Corrupts

President Obiang has been ruling Equatorial Guinea since 1979 when he overthrew his uncle in a military coup. Despite the country’s natural riches, rampant corruption has left most of its people living below the poverty line, according to the World Bank.

Ruling Equatorial Guinea is a family business. Obiang’s son and heir-apparent Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (nicknamed Teodorin) was appointed by his father to be the first vice-president of Equatorial Guinea in June 2016.

Teodorin is a huge fan of the late pop star Michael Jackson and lives in opulence reminiscent of his hero. American authorities investigated Teodorin’s US assets as early as 2004, laying claim to a Malibu mansion worth $30 million, along with luxury cars and six life-sized statues of the King of Pop, according to a New York Times report.

Official court data published by the US Department of Justice indicates that Teodorin amassed more than $300 million in assets while officially earning less than $100,000 per year.

“Through relentless embezzlement and extortion, Vice President Nguema Obiang shamelessly looted his government and shook down businesses in his country to support his lavish lifestyle, while many of his fellow citizens lived in extreme poverty,” said Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell.

In a settlement filed with the US Department of Justice in October 2014, Teodorin agreed to relinquish assets worth roughly $30 million. Assets were reportedly sold at auctions and the proceeds given to charities dedicated to helping the people of Equatorial Guinea, New York Times reported.

Currently, Teodorin’s assets are under scrutiny in France. In 2012, French authorities issued an arrest warrant for Teodorin and seized several luxury cars and his mansion in Paris on Avenue Foch. The mansion, nicknamed ‘Teodorin Obiang Palace,’ is located a few hundred meters from the Arc de Triomphe. According to news reports by El Pais, Teodorin spent some €25 million on the mansion.

And just this month, Swiss authorities seized 11 luxury sports cars in Geneva ‘as part of a preliminary investigation into alleged corruption,” the AP reported.

The Eastern European Connection

Reporters for OCCRP and 15min discovered that an Eastern European network of companies and people play an important role in the Obiangs’ schemes.

The role of one of those persons is well known. Court records from Spanish and American authorities directly and indirectly identify a former Soviet diplomat, Vladimir Kokorev, as a key player in Obiang’s network. In 2015, Kokorev and his wife, Yulia, and son, Igor, were arrested in Panama on charges from Spain that media say are related to the looting of Equatorial Guinea. A Spanish non-governmental organization had filed a civil claim against the Kokorevs for money laundering for the Obiangs. Kokorev is currently in a Spanish prison but authorities have refused to comment on the charges.

The Kokorevs had fled Spain in 2012, after Spanish law enforcement initiated an investigation focused on their business with the regime in Equatorial Guinea. The case was based on a civil complaint filed in 2008 by the Spanish Association for Human Rights (APHDE) working with the Open Society Foundation Justice Initiative. The complaint, which was taken up by prosecutors, alleged that the Kokorevs, via the country’s very lucrative shipping and oil industries, laundered more than $30 million on behalf of the Obiang regime.

The Kokorev connection was featured in money-laundering reports as early as 2004. One of them is the Riggs report by the US Senate. Named for the former Washington-based Riggs Bank that was used to siphon Equatorial Guinea money, the report mentions two Panamanian companies, Kalunga Co. S.A. and Apexside Trading Ltd., which were allegedly used to invest ill-gotten gains on behalf of the country’s ruling family.

An official report of the World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative identifies the Kokorevs as the managers of Kalunga Co. The report published by StAR also says that Kalunga’s money was allegedly used to buy properties for the Obiangs. The US Senate’s investigation stated that “at least one” of these two companies “may be owned in whole or in part” by President Obiang himself.

The investigation of money flowing through Riggs Bank revealed that Kalunga got more than $26.5 million in wire transfers from the Equatorial Guinea government’s account designated for receiving funds from foreign oil companies doing business in the country.

The report reveals that Riggs Bank had reason to believe that the Obiangs were behind the Panamanian accounts. According to the Senate document, the bank reached out to the president himself, but he “declined to provide any additional information about the wire transfers to these companies, other than to say that the wire transfers had been authorized.”

The Lithuanian Proxy and the President’s Ship

Reporters for OCCRP and 15min learned that while the Kokorevs’ investigation was drawing unwanted attention, another key player in the Obiangs’ Eastern European network was quietly working on their behalf.

Vladimir Stefanov is a Lithuanian citizen linked to both the Kokorevs and the Obiangs via documents assigning power of attorney, contracts and businesses.

Since 1999 Stefanov, together with Yulia and Vladimir Kokorev, managed a Panamanian company called International Shipping Advisors S.A. This company was established by Ismael Gerli Champsaur, a Panamanian lawyer who did work for the Kokorevs and was later subpoenaed by Spanish authorities in December 2015 to provide information.

In 1999 Gerli Champsaur set up another shipping firm in Panama, Intracoastal Trading Services SA. Stefanov, Kokorev and his wife, along with Fausto Abeso, President Obiang’s son-in-law, have all received in 2013 powers of attorney to conduct business on behalf of the company. Abeso is now the minister of civil aviation in Equatorial Guinea and was the country’s ambassador to Russia in 2005.

Fausto Abeso shaking hands with Vladimir Putin.

Fausto Abeso shaking hands with Vladimir Putin.

Stefanov’s most important Panamanian connection is to Glomar Supplies S.A., a company that is managing a fleet of cargo ships tied to Equatorial Guinea’s regime. One of those ships is known to be owned by Obiang, and others may be as well. Glomar is also a shareholder in a Lithuanian company, Minijos Salos, together with Stefanov’s daughter.

Stefanov received a power of attorney for Glomar Supplies which granted him the right to manage its bank accounts, conclude business deals and register movable or immovable property, including ships.

In an interview with 15min, Stefanov confirmed having the power of attorney for Glomar Supplies, but said it was exclusively for performing his duties as a director. He refused to disclose Glomar’s ownership. “It’s a commercial secret. Maybe I know [the owners], maybe I don’t,” said Stefanov.

Ghost Ships

Understanding Obiang’s ties requires looking at the vessels the company operates. Rio Ekuku, a cargo ship with the length of one and a half soccer fields, is one of the vessels in the Glomar-managed fleet. The ship was bought in April 2008 from a Chinese company by Backyard Marine Services Inc., another Panamanian company established by the Panamanian lawyer Gerli Champsaur. Backyard was represented during the purchase of the ship by Vladimir Stefanov.

Subsequent records seen by OCCRP allege that Rio Ekuku went through a puzzling chain of secretive transactions involving tens of millions of dollars. The scheme, often seen in money-laundering or tax evasion cases, followed a pattern in which a set of companies connected to each other sold assets amongst themselves. The sales are part of the Spanish investigation.

Reporters met Stefanov at his office in the Lithuanian port of Klaipėda, where he said that the alleged chain of consecutive sales are “either fiction or [a] setup”.

He said that Rio Ekuku changed ownership only twice: “I’ve heard this tale. I will not confirm it.”

Stefanov said such a sale would require changing the vessel’s country of registration which would require a lot of paperwork. “We checked it. None of these ships went through this procedure.”

Stefanov blames Gerli Champsaur for the paperwork and any problems.

Rio Ekuku appears in the center of a chain of transactions among Panamanian companies involving tens of millions of US Dollars.

Rio Ekuku appears in the center of a chain of transactions among Panamanian companies involving tens of millions of US Dollars.

While Stefanov would not identify the vessel’s owner, he said an Equatorial Guinea company called Smart is now the owner of the Rio Ekuku and three other Glomar-managed vessels which reporters confirmed. However, he indirectly linked the ownership to the Obiang family by mentioning that the owner of the vessel contracted Stefanov to manage a shipyard in Equatorial Guinea, which OCCRP has learned is owned by the Obiangs.

Stefanov flatly denied any connection to the Obiangs. Later, when confronted with documents showing his ties to former ambassador Fausto Abeso, Obiang’s son-in-law, Stefanov refused to comment further.

Despite these claims, 15min obtained a document that connects the Rio Ekuku directly to the ruling clan in Equatorial Guinea. Reporters met a sailor who was employed by Glomar in the Lithuanian port of Klaipėda where the Panamanian company has had an office since 1998.

His name is being withheld for security reasons but he was one of many Lithuanian sailors employed to work on the Rio Ekuku and other vessels tied to Glomar. He provided his work contract for the Rio Ekuku, concluded shortly after the ship was built, that lists an Equatorial Guinea company called Abayak S.A. as the true owner of the cargo ship.

He also said that his initial employer was Glomar but added that new contracts were issued to the crew once they boarded the Rio Ekuku. Company records obtained by OCCRP from the Equatorial Guinea registry of companies show that the shareholders of Abayak are President Obiang, his wife and his son.

After being confronted with this evidence, Stefanov repeated that the vessel is under a different ownership now. “The owner of the vessel is a company called Smart. I don’t know where you found Abayak … The sailors can say whatever they want. I can send you a copy of the document where the owner is indicated,” he said.

Abayak is mentioned in the US Senate Riggs report as a partner of multinational corporations such as Exxon Oil and Marathon in a range of oil and land deals in Equatorial Guinea. The report also states that the company is controlled by the president.

The Glomar-managed cargo fleet is not the only connection between Stefanov and secretive businesses in Equatorial Guinea.

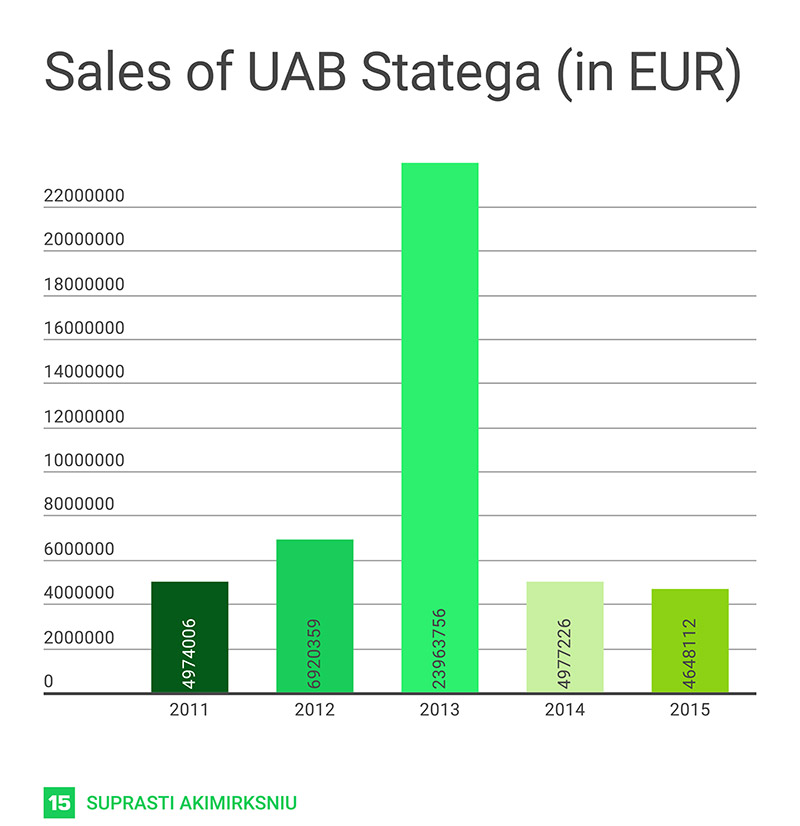

In 2011, Stefanov’s Lithuanian company Statega was hired by Glomar Supplies for € 80 million (about $110 million) to build and subsequently operate for 20 years a shipyard in Malabo, the capital of Equatorial Guinea. Both the shipyard construction contract and the shipyard lease agreement mention that Glomar is acting on behalf of an Equatorial Guinea company called Asaba Astillero SA.

Shipment records listing exports to Ukraine and imports from Russia connect this firm to the same Abayak SA that belongs to the Obiangs. Statega’s financial records also recorded that the Lithuanian company has a valid lease agreement in Equatorial Guinea that terminates on Feb. 1, 2031, which coincides with the terms of the lease agreement obtained by OCCRP.

Stefanov would not say who owns the shipyard. “Statega has a contract to manage the shipyard. The shipyard doesn’t belong to the government. It’s a private company,” he said.

His lawyer Svetlana Baracevičienė, who also attended the interview, said documents obtained by OCCRP and 15min were forgeries, later adding that the forgeries were “obtained illegally”. Baracevičienė had an additional connection to Stefanov’s family: records obtained by 15min show that Marius Stefanov, Stefanov’s son, used to be the director of Tesinita, a now-dormant Klaipėda-based company owned by Baracevičienė.

“Some are trying to step on President Obiang’s foot”

Stefanov claims that the Kokorev family is being scapegoated because it got caught in the crossfire between competing interests in Equatorial Guinea.

He says the Spanish prosecution is due in part to resentment by the Spanish government because Obiang allowed only the Americans to drill for oil in his country.

Of Equatorial Guinea itself, he said, “Yes, it is a dictatorship. Later, the Americans tried to overthrow it. But it is Africa. Let’s not get into their internal matters.”

He said Spanish authorities aligned themselves with the opposition in Equatorial Guinea, a group made up of “Obiang’s relatives, who the president had removed from power leading to a conflict where the relatives are posing as democratic opposition to a dictator.”

While the 2004 US Senate report on Riggs Bank named the company Kalunga, run by the Kokorevs, as a tool for money laundering, Stefanov says he believes Kokorev, who he has known for decades, was unjustly accused.

Kokorev “was framed for money laundering. He allegedly stole $28 million on behalf of the president ... Some are trying to step on President Obiang’s foot. Others might be trying to seize [Kokorev’s] properties,” he said.

The Aftermath

Vladimir Stefanov (Photo by: Vidmantas Balkūnas / 15min.lt) Weeks after reporters talked to Stefanov, he was asked to step away from Glomar and the businesses run by the Panama company. “They said, ‘Thank you and goodbye.’ Maybe they wouldn’t have if this scandal hadn’t happened. Because of Kokorev. Because Mr. Gerli [Champsaur] began telling everything.”

Vladimir Stefanov (Photo by: Vidmantas Balkūnas / 15min.lt) Weeks after reporters talked to Stefanov, he was asked to step away from Glomar and the businesses run by the Panama company. “They said, ‘Thank you and goodbye.’ Maybe they wouldn’t have if this scandal hadn’t happened. Because of Kokorev. Because Mr. Gerli [Champsaur] began telling everything.”

Stefanov also acknowledged that other businesses that belong to his holding company Statega--including a real estate company in Spain called Premium Trust--are in trouble because of the cases. “All of our attempts to find out what’s happening with the assets of Premium Trust give no result. Since the case of Mr. Kokorev is labeled as a state secret, the secrecy automatically covers Premium Trust,” he said.

Stefanov says he believes the figure behind the problems is Gerli Champsaur, Kokorev’s former lawyer who participated in the formation of numerous companies tied to the network.

“I don’t know what happened between them [Gerli Champsaur and Kokorev], but it’s an attack party. He’s attacking, he’s making accusations. As far as I understand, he’s the principal witness in Spain,” he said.

Gerli Champsaur, reached by OCCRP, denied any knowledge of Kokorev’s businesses with Equatorial Guinea, saying he is just a formation agent who established companies for Kokorev.

Gerli Champsaur denied the characterization: “I did not cooperate and I’m not cooperating with the Spanish police in the Kokorev case. … I received a subpoena from a Spanish judge for the 1st of December 2015 and I answered the questions that I have been asked,” he said

Since the interview with Stefanov, the fleet of vessels managed by Glomar changed ownership again. Glomar disappeared from the management of some vessels tied to Equatorial Guinea.

According to the most recent data from Equasis, Smart S&P SA is now listed as the registered owner of Rio Ekuku, Mikue 3 and Rio Utamboni. The company is officially acting as ‘care of’ ITS International Trades & Services, a company registered in Belgium. Also, two of the ships have recently dropped their Panamanian flags. Rio Ekuku with Rio Utamboni were reregistered in an even more secretive jurisdiction: Belize.

"Unfortunately, after our conversation, I have trouble at work. Therefore, I am no longer willing to talk about these subjects," Stefanov said when contacted for the last time.

"You did nothing, but I have trouble, because you ask questions as if I'm working for some kind of an enemy. When I talked about it at the company, they said 'Thank you, we probably no longer need your services, goodbye'".

When asked to specify what company he meant, Stefanov hung up.