For years, the Avilon owners’ dealings were hidden in a maze of corporations registered in various notorious tax havens, including Cyprus, the British Virgin Islands, and the Marshall Islands -- as well as the US state of New Jersey.

But Chaika’s connections to Avilon were uncovered in part when reporters for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting project (OCCRP) obtained court files from a pair of lawsuits filed in the US by warring investors.

The Avilon Automotive Group, which has sold hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of cars to the Russian government and state organizations, has been in business since 1997 and is one of the leading Mercedes-Benz, Ford, Hyundai and BMW dealers in Russia. Its customers include average citizens, well-heeled private clients, and government and law enforcement agencies.

High-ranking officials from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service (the former KGB), the Presidential Administration, and the General Prosecutor's Office ride in Avilon cars. Over the last six years, the company has won state contracts worth at least 17 billion rubles (US$ 286 million at the current exchange rate), which does not include significant additional contracts for service and maintenance.

But the lawsuits, filed in US federal and state courts in 2016, revealed previously hidden details about the firm. The cases show that even as Avilon was benefiting from state contracts with various security agencies in Russia, one of its owners was a business partner of the high-ranking officials who ran those same agencies.

While this conflict of interest may technically not be illegal under Russian law, watchdogs decry this as a common Russian pattern, wherein taxpayers' money flows to those with close ties to the elite.

Elena Panfilova, vice president of Transparency International-Russia, said the Avilon case “once again shows there is an inner circle of elites in Russia bound by such affiliations. This circle is tight, and we stumble upon it time after time.”

The People Behind Avilon

About 90 percent of Avilon Automotive Group is equally split between Alexander Varshavsky and Kamo Avagumyan.

Varshavsky is a naturalized American. He lives in Holmdel, New Jersey, an upscale enclave southwest of Manhattan, and owns a number of US companies which control assets in Russia with well over US$ 1 billion dollars in turnover, including Avilon.

In 2014, he was arrested by federal agents in an unrelated matter as he disembarked from a plane at New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport. He was charged with failing to report foreign bank accounts from which, the complaint alleges, millions of dollars had poured into his US accounts. However, the case against him was dismissed in March 2015. “Further prosecution of this charge is not in the interests of the United States at this time,” said the order.

Avagumyan, an ethnic Armenian who is believed to be a Russian citizen, is a successful businessman in Russia. He is known in the Armenian philanthropic community for his charitable giving, and his son’s wedding in Moscow was even attended by Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan, according to Armenian media. He also “performs representative duties” for Armenia’s General Prosecutor’s Office in Russia, he told OCCRP.

On Trial In New York

At the heart of the dispute that landed Avilon in court are a series of loans that Avagumyan and Avilon had madeto companies controlled by Alexander Zheleznyak and Sergey Leontiev, then the owners of a major Russian bank called Probusinessbank.

“Zheleznyak was a friend of mine for a long time,” Avagumyan told OCCRP, describing how they started doing business together. “He made me an offer to invest my money at a quite high interest rate,” he said.

The arrangement had apparently worked well for a number of years. Avagumyan would provide funds (in bags of cash, according to his own later testimony) to the bank owners’ representatives. As a guarantee, Avagumyan said, he would receive promissory notes in the name of his son, Karen, from offshore companies or from LIFE Financial Group, which were connected to the Probusinessbank owners.

The funds would be invested in LIFE and the offshores, and a year later, Avagumyan would get his money back with an interest of 10-12 percent.

But in the summer of 2015, the arrangement turned sour. That Aug. 12, the Central Bank of Russia revoked Probusinessbank’s license, saying the bank was more than $1 billion in the hole, citing bad loans made for fake assets, among other offenses.

The news caused consternation among investors, and on Aug. 14, Avagumyan’s Avilon co-owner, Varshavsky, met with Zheleznyak and Leontiev in Moscow, and later again in London, seeking assurances that $100 million that had been loaned over the years would be repaid despite Probusinessbank’s problems. But that didn’t happen.

Former Probusinessbank president Sergei Leontiev in Moscow on Feb. 4, 2009. (Photo: Yury Martianov/Kommersant)

Former Probusinessbank president Sergei Leontiev in Moscow on Feb. 4, 2009. (Photo: Yury Martianov/Kommersant)

Zheleznyak and Leontiev fled Russia. After a few months of unsuccessful negotiations, during which only $17 million were repaid, the parties sued each other.

In the first suit, filed in the federal court for New York’s Southern District, Leontiev claimed that Varshavsky had caused him emotional distress, threatening to use his extensive contacts in the Russian government to obtain payment.

“In an effort to intimidate Mr. Leontiev, Mr. Varshavsky has repeatedly threatened to bring criminal charges against Mr. Leontiev and Mr. Zheleznyak,” the federal court civil complaint read. “Mr. Varshavsky has also threatened to link Mr. Leontiev’s name to terrorism financing. Upon information and belief, Mr. Varshavsky is capable of carrying out these threats due to his well-established connections with government officials and other individuals in Russia.”

According to court documents, surreptitious recordings Leontiev had made of his London talks with Varshavsky surfaced as evidence during the proceedings. In the recording, Varshavsky tells Leontiev that he simply would not be able to leave without a written guarantee that the money would be paid back.

Avilon co-owner Alexander Varshavsky (left) with Andrei Lomakin, co-owner of Aston Martin Russia. (Photo: Valeriy Levintin/Kommersant) “I can’t fly to Moscow, understand? They’ll rip my head off,” Varshavsky said. “I don’t know what will happen. I don’t even want to think about it.”

Avilon co-owner Alexander Varshavsky (left) with Andrei Lomakin, co-owner of Aston Martin Russia. (Photo: Valeriy Levintin/Kommersant) “I can’t fly to Moscow, understand? They’ll rip my head off,” Varshavsky said. “I don’t know what will happen. I don’t even want to think about it.”

From the recordings presented in court, it isn’t clear exactly who “they” were.

Leontiev appears to interpret Varshavsky’s words as a threat: “You're saying that you are powerful people,” he says in the recording, “that behind you are top prosecutors, [and] (Russian Prosecutor General Yury) Chaika's son. Just great.”

But in an interview with OCCRP, Varshavsky said that, while knowingly recording the conversation, Leontiev had been trying to provoke him into invoking the senior officials himself, to make him appear as an aggressor.

“I have no ties to the Russian prosecution,” Varshavsky said. “I never threaten anyone, it’s just not me.” Instead, he said, he was only trying to make sure his friends and partners, to whom he had recommended investing in Leontiev’s operation, and who also had lost money, were also paid back. These friends included Boris Zuyev, also present at the meeting.

The Investigative Committee Connection

Boris Zuev, who also claimed to be owed money by Leontiev, also attended the London meeting in hopes of securing repayment.

Notably, Zuev -- whom Varshavsky described as a friend -- is a former deputy head of the Main Directorate for Provision of Activities of the Investigative Committee of Russia. This is the department that is, among other things, responsible for the procurement of vehicles for the Investigative Committee.

While Zuev worked as a public servant in the Investigative Committee, Avilon was one of the leading suppliers of cars for investigators. Between 2007 and 2010, the company got 700 million rubles (nearly $12 million) from Investigative Committee contracts, according to a Novaya Gazeta report.

Avagumyan said he wasn’t acquainted with Zuev during the time of his public service.

“I met him at Vnesheconombank [where he worked later]. He worked there as a head of a department and we -- me and Varshavsky – went there to discuss the loan for our greenhouses, for our agricultural business. It didn’t work out though,” said Avagumyan.

Boris Zuev was not available for comment.

According to the proceedings, Avilon’s side believes that Leontiev filed the lawsuit to avoid repaying the debt. In the end, both sides claimed victory. The court dismissed Leontiev’s claims that Varshavsky had intentionally inflicted emotional distress, but also established that Leontiev did not owe any money to Varshavsky in a personal capacity.

Avilon subsequently filed a countersuit in New York State’s Supreme Court, seeking the lost money. The countersuit is still ongoing.

By early 2016, Probusinessbank’s top managers were being investigated in Russia for allegedly embezzling about 2.5 billion rubles (about $44 million). Several managers and others believed to be affiliated with the bank were arrested. Zheleznyak and Leontiev, who had fled to the US after the bank was shut down, were put on a wanted list by the Russian Ministry of the Interior.

Both Avilon principals agreed to talk to OCCRP, while neither Zheleznyak nor Leontiev could be reached for comment.

Avagumyan told OCCRP that Zheleznyak had been worried about facing criminal prosecution in Russia and even asked the Avilon owners not to file any criminal complaints with the Russian authorities.

For their part, both Varshavsky and Avagumyan strongly deny any involvement in the Russian legal proceedings against the bank’s owners, arguing that this would not have helped them get their money back.

The Chaika Connection

Kamo Avagumyan and Igor Chaika, Prosecutor General Yury Chaika's other son, at the Saint Petersburg Economic Forum in June 16, 2016. (Photo: Kristina Kormilitsyna/Kommersant) The New York cases are important because of what they reveal, almost incidentally, about the Avilon owners’ connections. “Chaika’s son,” mentioned in Leontiev’s recording as someone who stands behind the Avilon owners, likely refers to Artyom Chaika, son of Russian Prosecutor General Yuri Chaika. The court documents led to the revelation that Avagumyan is business partner of the younger Chaika in a five-star hotel on Greece’s Chalkidiki peninsula called the Pomegranate Wellness Spa.

Kamo Avagumyan and Igor Chaika, Prosecutor General Yury Chaika's other son, at the Saint Petersburg Economic Forum in June 16, 2016. (Photo: Kristina Kormilitsyna/Kommersant) The New York cases are important because of what they reveal, almost incidentally, about the Avilon owners’ connections. “Chaika’s son,” mentioned in Leontiev’s recording as someone who stands behind the Avilon owners, likely refers to Artyom Chaika, son of Russian Prosecutor General Yuri Chaika. The court documents led to the revelation that Avagumyan is business partner of the younger Chaika in a five-star hotel on Greece’s Chalkidiki peninsula called the Pomegranate Wellness Spa.

The hotel is well known because of a video that emerged as part of a joint investigation by OCCRP partner Novaya Gazeta and opposition activist Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation which drew millions of views on Youtube.

The video shows the younger Chaika and Olga Lopatina, the ex-wife of Deputy Prosecutor General Gennady Lopatin, cutting the ribbon at the hotel’s opening in May 2014.

It was quite a party. Relatives of the top brass in the Russian Prosecutor’s Office invested millions of euros in the hotel and celebrated in style with a military orchestra and fireworks. The popular Russian singer Philipp Kirkorov gave a performance, and Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky gave a speech.

The investigation caused a great stir among the public, revealing that the top prosecutors’ relatives owned hotels, factories, and luxury villas all over the world. Lopatina also ran a joint company with the wives of leaders in the former gang headed by Sergei Tsapok, one of the deadliest in Russia’s rich history of organized crime.

But the scandal seemed to have little effect on Yuri Chaika’s career -- he was appointed for a third term in 2016. Nor is there evidence that it in any way harmed his son’s business activities.

Artyom Chaika and Lopatina are major investors in the Pomegranate Spa, each currently holding 21.25 percent of the shares. Another 42.5 percent is owned by a Cypriot company, Amiensa Holdings, whose ultimate owners were hidden behind a chain of offshore corporations.

But according to the US court files and the Cyprus company register, Avagumyan owns at least half of Amiensa Holdings. Avagumyan told OCCRP that he owns 21.25 percent of Pomegranate, with an identical stake held by Amiensa’s other investor, Samvel Karapetyan of the Tashir Group of Companies, a major construction and real estate developer.

“This was an offer from my partner Samvel Karapetyan. We went there one time, I looked at it and agreed to became his financial partner. We jointly own our share but the project is managed by his office, by his lawyers. The sum of the investment is a commercial secret, and I can’t disclose it,” Avagumyan told OCCRP.

He insists his decision to invest in the Greek hotel was not an attempt to help relatives of top Russian prosecutors.

“I don’t communicate with them,” he said. “I’ve never had any personal relationships with Artyom Chayka, we are not talking to each other over the phone, we are not friends. But at least, I met him once. As for Olga Lopatina, I have never even seen her. The press reported that I had attended the opening ceremony of the hotel but I hadn’t.”

From Contacts to Contracts

Given the connections now revealed to exist between Avilon’s co-owner and top Russian prosecutors, the company’s success at attracting government contracts appears in a new light.

Almost every branch of the Avilon Group relies on such contracts or support. But most go to Avilon AG, which supplies cars to most of Russia’s law-enforcement agencies.

One of Avilon’s most important state customers is the Office of the Prosecutor General, which since 2011 awarded Avilon contracts worth 700 million rubles (around $12 million at the current exchange rate).

There have also been problems. In 2013, Mercedes-Benz RUS (the official distributor in Russia) tried to end its dealership contract with Avilon. According to Forbes, the German manufacturer had a number of complaints, including that Avilon had sold cars to state institutions for almost 1.5 times over the recommended price. Avilon successfully defended its contract in the Moscow Arbitration Court.

But the connections between Avilon’s owners and prosecutors may go beyond the Pomegranate Spa. Court documents indicate that the Avilon investors may have provided financial support to the daughter of Deputy Prosecutor General Saak Karapetyan.

A Favor for the Family?

During negotiations between Varshavsky and Probusinessbank, lawyers for both parties drew up a draft settlement agreement. The document, which was never signed, listed all the promissory notes of the offshore companies and LIFE Financial Group that were given to investors.

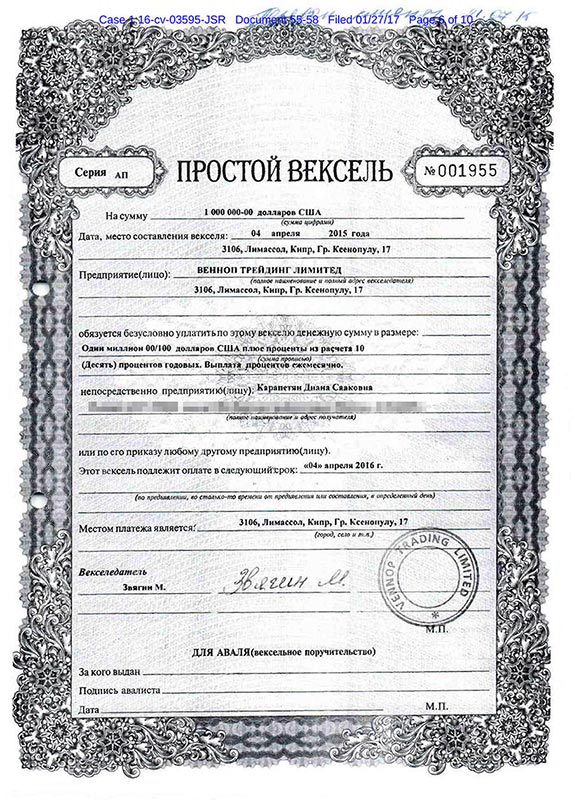

A promissory note worth $1 million in the name of Diana Karapetyan. Among those holding notes were Avagumyan’s son Karen -- and a young woman named Diana Karapetyan.

A promissory note worth $1 million in the name of Diana Karapetyan. Among those holding notes were Avagumyan’s son Karen -- and a young woman named Diana Karapetyan.

This is Saak Karapetyan’s daughter, and she holds promissory notes worth $4 million issued in 2015 from a Cyprus company called Vennop Trading.

Reporters for OCCRP were unable to find any substantial sources of income that could explain how Diana Karapetyan came to possess such wealth. She is 32, and, according to her Facebook profile, she lives in London. In Russia, Diana Karapetyan, her mother Karine, and two relatives own a company called ARDT-7, which reported a loss in its 2015 financial report to the Federal State Statistics Service.

Her father Saak has worked in the Soviet and Russian justice systems since the 1980s. In the early years of this century, he worked under Chaika at the Ministry of Justice, and followed his boss to the Prosecutor General’s Office in 2006 to head the General Department of International Legal Cooperation. He later became Chaika’s deputy. In 2015, Saak Karapetyan's declared income was 3.5 million rubles ($50,000).

On paper, his wife Karine Karapetyan is the richest in the family – she declared 43 million rubles (about $ 610,000) in income, in 2015. She partially owns a plot of about three acres of land with a group of buildings in the center of Rostov-on-Don, Russia’s biggest city in the Southern Federal District. The buildings are rented to a variety of tenants: a movie theater, shopping mall, and offices.

One line in the draft settlement agreement between Avilon and Avagumyan and Probusinessbank’s owners is puzzling.

The agreement says that Avagumyan and Avilon provided Zheleznyak and Leontiev “directly, or to their affiliated companies, a number of loans in various forms,” and then lists all the promissory notes, including those belonging to Diana Karapetyan.

A word-for-word reading of the text suggests the notes were bought not by Karapetyan, but by Avilon or Avagumyan in her name.

Varshavsky and Avagumyan stated in court that they do not know who Diana Karapetyan is, nor how her name appeared in the settlement agreement’s text.

However, Diana Karapetyan is friends on Facebook with Avagumyan’s son Karen and another of his relatives.

While speaking with OCCRP, both Varshavsky and Avagumyan affirmed they are not acquainted with Diana Karapetyan.

Diana Karapetyan did not respond to messages sent to her Facebook page.

Avagumyan claimed to have no social or business affiliation with Saak Karapetyan. “I just know he works there [in the Prosecutor’s Office]. I don’t socialize with him, I don’t go around with him, we don’t drink vodka together. We are not friends, I don’t meet with him. I only came across him a couple of times when prosecutors from Armenia visited. He also met them, since he was head of the International Department,” said Avagumyan.

Varshavsky believes the name of Diana Karapetyan was intentionally inserted into the draft agreements by Leontiev’s people to “politicize the case.”

“All those tables [listing the promissory notes] were presented [to court] not by us, but by Leontiev’s lawyers. This is probably one more way to politicize the whole affair. I don’t know who this Karapetyan is who has a daughter named Diana. And I don’t know Diana herself. I’ve never seen her in my life – this I can state under any oath. And I have never represented these people,” Varshavsky said to OCCRP reporters.

But the US court documents seem to contradict some of these statements by Avilon’s co-owners. Among them is a letter from Robert Stahl, Varshavsky’s US lawyer. The letter, with the subject “Debt confirmation,” is addressed to Leontiev’s lawyer, Robert Weigel. Attached to this letter are a number of bank guarantees and promissory notes, including those in the name of Diana Karapetyan.

The court documents also contain a number of letters sent by Vitaly Popov, the head of Avilon’s Legal Department. In one of them, Popov wrote: “We propose that you review the possibility of documenting these relationships by making agreements under which the persons specified [Leontiev and Zheleznyak] acquire the relevant promissory notes and claims from the current holders.” In other words, Leontiev and Zheleznyak would buy the promissory notes directly from Avagumyan, Avilon and other holders.

The drafts of these buy-and-sell agreements were presented in the courts as well. Among them is “Agreement No. 2 on Promissory Note Acquisition” from Diana Karapetyan.

These documents prove that at least Avilon’s lawyers knew about the promissory notes in the name of Diana Karapetyan and even tried to make Leontiev and Zheleznyak buy them back.

The General Prosecutor’s Office declined to clarify how the daughter of the Deputy Prosecutor General could have made an investment worth $4 million. The press office of the General Prosecutor’s Office suggested OCCRP contact Diana Karapetyan directly, but she never responded to a request for comment.

Avagumyan insists that his joint projects with relatives of top officers of the Prosecutor’s Office don’t help his company get state contracts. He said that neither his company nor he personally can be considered as affiliated parties with those relatives.

“Avilon takes part in state tenders under the same conditions as our competitors. And we don’t always win, by far. Over the last three years, Avilon sold 85,000 cars. Out of those, only 81 were sold to the Prosecutor’s General Office,” he said.