In the space of a day last July, he fired his deputy prime minister and attorney general and sidelined members of a parliamentary committee looking into the apparent theft.

With the press increasingly muzzled and the country’s opposition leader behind bars, Najib appeared to have weathered the crisis unscathed.

That is, until the United States stepped in. On July 20, the US Department of Justice announced it was launching a case to recover more than US$ 1 billion in assets out of a total of about $3.5 billion allegedly stolen from the sovereign wealth fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB).

That amount – the biggest sought so far in a foreign kleptocracy case – is part of an evolving US strategy to go after corrupt foreign leaders through a specialist unit known as the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative.

Set up in 2010 with five prosecutors, the initiative has since tripled in size, seeking about $2.8 billion from figures including the late Nigerian ruler Soni Abacha and Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of the dictator of Equatorial Guinea.

The previous record for assets sought by the Justice Department was about $850 million linked to Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of late Uzbek President Islam Karimov, who is accused of squeezing of more than $1 billion in bribes from foreign firms.

The initiative targets a particularly sticky problem: the world’s most corrupt leaders tend to have total impunity at home, and are untouchable abroad.

“In the criminal kleptocracy realm, if you’re focused on the head of the state, if that person is still in that position, then under the Vienna Conventions they may have head-of-state immunity,” M. Kendall Day, the head of the Justice Department’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section, told the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

So what do you do when you can’t take kleptocrats to court? You take their loot to court instead.

The Justice Department’s initiative uses civil asset forfeiture, a sometimes controversial legal method that allows law enforcement to seize assets suspected of being proceeds of a crime, without ever actually charging suspected perpetrators. It’s a strategy used in concert with the seeking of record settlements under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a 1977 law that criminalizes bribe-paying by US companies.

“The US is clearly the leader... in having developed this kind of peculiar doctrine (of civil asset forfeiture),” said Ken Hurwitz, a senior legal officer at the Open Society Justice Initiative. (Disclosure: Open Society Foundations fund some OCCRP projects).

“In the US, it operates as a legal fiction that instead of prosecuting a person who has done a crime, you’re prosecuting an asset for being an either an instrumentality of a crime, or proceeds of a crime,” he said.

In Malaysia’s 1MDB case, the scale of the alleged spoils is remarkable. Among the assets being sought are a dozen luxury properties, a private jet, two Monets, one van Gogh, and the rights to the 2013 Hollywood film, The Wolf of Wall Street. Prosecutors say the latter, an Oscar-nominated film about white-collar crime, was funded with tens of millions of dollars stolen from Malaysian taxpayers.

American law enforcement allege figures linked to 1MDB, including Najib’s stepson Riza Aziz and Malaysian businessman Jho Low, stole more than $3.5 billion from the fund in three stages between 2009 and 2012, using a series of shell companies with bank accounts in Switzerland, Luxembourg, Singapore and the US.

Najib is not named in the case, which instead details how an individual referred to as “Malaysian Official 1” saw more than $700 million linked to 1MDB flow through his bank accounts. The opposition, media reports, and at least one government minister have identified Malaysian Official 1 as Najib.

The Justice Department’s July announcement was a bombshell in Malaysia, where civil society has all but given up hope of local institutions getting to the bottom of the scandal, said Nurul Izzah Anwar, the daughter of imprisoned opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim.

“I think in terms of the public psyche, everyone was jolted by the report and statements made by the Department of Justice because it was so explicit and clear-cut to the point naming this as sort of a scandal by kleptocrats,” she said. “It really shocked everyone in the country.”

A spokesman for Najib declined an OCCRP request for comment. The prime minister has consistently denied any wrongdoing in the 1MDB case.

For the Justice Department’s Day, the case shows that the US is increasingly serious about going after foreign corruption. It’s an attitude that is at least partly born of national self-interest, he said.

“Our financial system is one of the most liquid and transparent in the world, and that’s why kleptocrats and corrupt officials are going to try to park their money here in the US,” Day said.

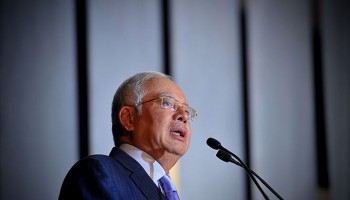

“And that’s frankly one of the reasons we have to be so vigilant through the kleptocracy program, because to protect the very transparency and soundness of our financial system, we have to keep hot money flows out. They distort our markets (and) they undermine our very system of financial reporting: a system that is based on the truthfulness of the information coming in.” Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak (Photo: en.kremlin.ru)

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak (Photo: en.kremlin.ru)

Increasing US attention to kleptocracy cases is having global effects, Open Society’s Hurwitz said. In the 1MDB case, Singapore and Switzerland – both countries with a history of financial secrecy – appear to have worked closely with the US, freezing millions believed to be linked to the scam. (The Justice Department’s Day declined to answer in detail questions about coordination between the US and other countries in the case.)

But while the US is taking foreign leaders to court for record amounts, there are significant potential roadblocks.

So far, the government’s capacity to win cases has only been partially tested. Of the $2.8 billion that has been sought, only $150 million has been won so far. The biggest cases, involving 1MDB and Karimova, are not expected to go to trial any time soon.

Shruti Shah, vice president of programs and operations at Transparency International in the US, notes the US still offers many dark channels allowing dirty money to move unseen.

While it “would be even better… to prevent these assets from being stolen (in the first place),” she said, “we need to do something about intermediaries – bankers, lawyers and the real estate industry.”

According to an investigation by the New York Times, nearly half of US homes valued at more than $5 million are owned by shell companies. States including Delaware, Nevada and Wyoming allow such companies to be registered with little or no identifying documentation.

“I would need more information to renew a library card than to open an LLC (limited liability company) in Delaware,” Shah said.

The US is making some effort to close those gaps. The Treasury Department this year rolled out a pilot project in cities including New York, Miami and San Francisco requiring the disclosure of the names behind cash purchases of property. A bill introduced in Congress in February would mandate the declaration of the people actually behind the shell companies.

Even if US law enforcers do win their cases, getting the money back to the countries of origin carries the risk of it being pilfered all over again.

So far, the preferred option is to give it to charity. In 2007, the US and Kazakhstan settled a bribery case by agreeing to transfer more than $115 million in seized money to a World Bank-supervised foundation operating in the country, rather than returning the funds to the government.

With Najib still firmly entrenched in Malaysia, any returned money would likely have to be treated the same way, Malaysia’s Nurul Izzah said.

Anything else would be “akin to given it back to the thief who stole it in the first place,” she said.

This article was corrected on 23 September, 2016 to reflect the fact that the US and Kazakhstan agreed in 2007 to return seized money to a World Bank-supervised foundation. OCCRP regrets the error.