President Putin’s decades-long crackdown on Russian press freedom is a well-established, even banal fact. So it’s easy to miss the significance of the latest round of repression in Moscow. But it’s not just more of the same.

Over the last year, the Kremlin’s assault on independent Russian journalism entered a new, qualitatively different stage. Dozens of major media outlets and individuals who report critically about the government have been targeted by a law designed to make it nearly impossible for them to continue their work.

Modeled superficially on legislation that exists in other countries, the law requires its targets to publicly declare themselves as “foreign agents,” a term that carries the same alarming implications in Russian as it does in English. They must also submit to a set of onerous requirements.

Here’s how it works — and why it matters.

Where did the “foreign agent” law come from and how does it work?

President Putin signed Russia’s first “foreign agent” law, which targeted non-profit organizations, just months after beginning his third presidential term in 2012.

That year’s election had been followed by the largest and most intense protests in Russia since the break-up of the Soviet Union, and the law was accompanied by a host of other restrictive measures against the country’s civil society.

The foreign agent law allowed the Ministry of Justice to declare non-profits as “organizations carrying out the functions of a foreign agent” if they engaged in political activity and received funding from abroad. Among the first organizations designated as such was the Memorial Human Rights Center, which has worked since the 1980s to highlight human rights violations and preserve the historical memory of Soviet repression.

A media version of the foreign agent law, which similarly targets outlets or individual journalists that receive foreign funding, was passed in November 2017. Officials justified the measure as a “mirror response” after the United States designated the American branch of Russian state outlet RT as a foreign agent earlier that year.

But while the American and Russian “foreign agent” designations have some similarities, their effects in two very different legal systems are nowhere near equivalent.

How does the Russian law work? How’s it different than the American version?

RT America was pressured to register as a “foreign agent” after an intelligence report found that it played a role in the Kremlin’s efforts to interfere with the 2016 presidential election. The designation, carried out under the U.S. Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA), can be applied when an outlet is acting “at the order, request, or under the direction or control” of a foreign party — merely accepting foreign money is not sufficient to mandate registration.

In Russia, the scope to declare an organization a “foreign agent” is much broader. Outlets that receive any foreign funding at all are vulnerable. Their employees may be declared foreign agents themselves, subjecting them to individual reporting requirements and steep fines for errors or omissions.

A Russian journalist can be declared a “foreign agent” merely for receiving money from a friend abroad. Even being reimbursed for expenses on a foreign press tour can serve as pretext for a designation.

What happens if you’re declared a “foreign agent”?

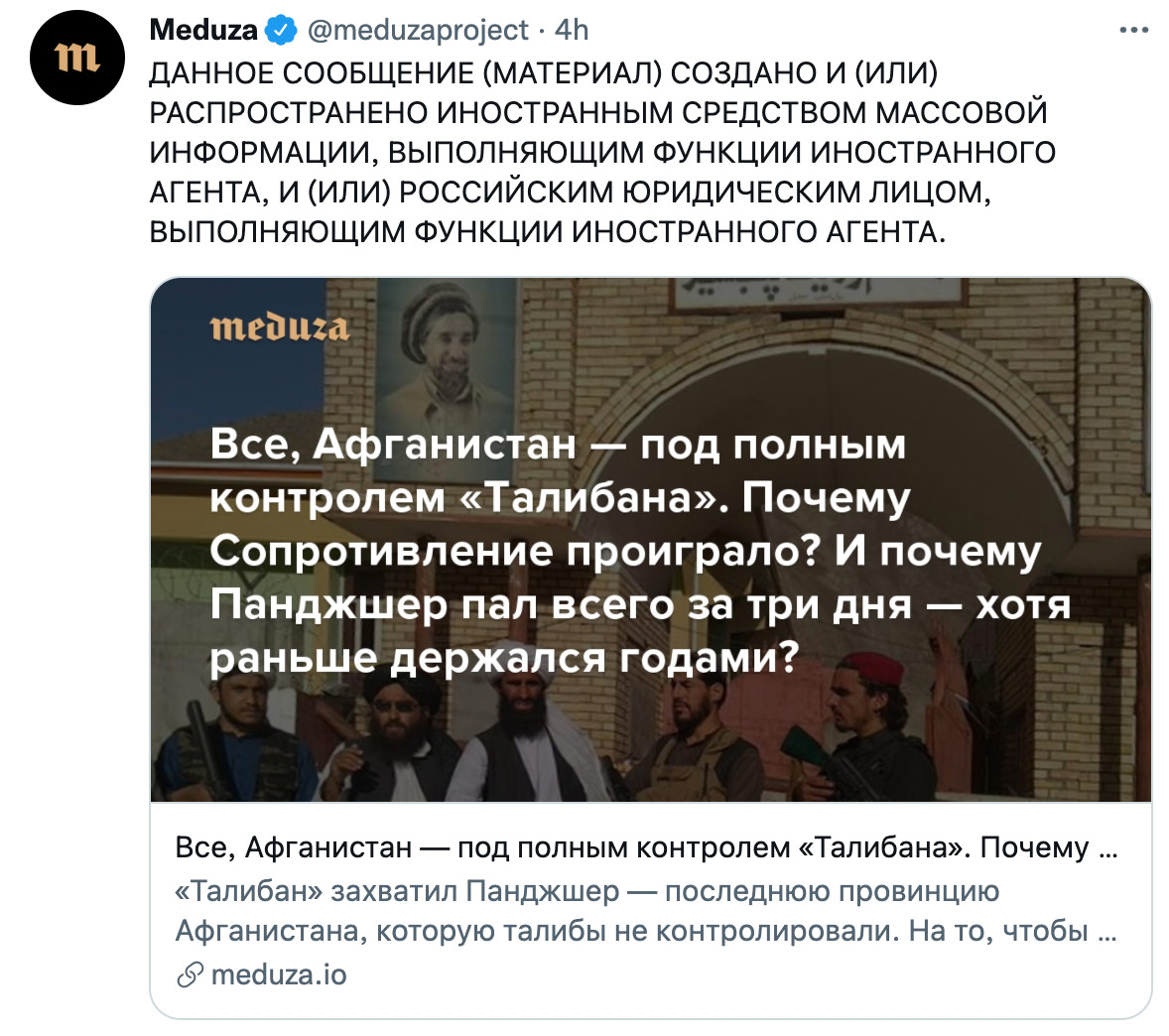

Media outlets and individual journalists designated as foreign agents must mark all their publications, including even their tweets, with a clumsy and ominous 24-word declaration: “This message is created and/or distributed by a foreign media outlet carrying out the functions of a foreign agent, and/or by a Russian legal entity carrying out the functions of a foreign agent.”

Roskomnadzor, the country’s media regulator, explains that this is “intended to inform the audience that the materials disseminated by these outlets are pursuing the interests of other states.”

In practice, the distracting messages make the outlet’s materials difficult to stomach for readers unfamiliar with the repressive nature of the requirement. They also poison relationships with sources and advertisers.

Even social media posts that have little to do with Russian politics — such as this explainer about the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan — must be accompanied by the intrusive “foreign agent” label. (Credit: Twitter / @meduzaproject)

Even social media posts that have little to do with Russian politics — such as this explainer about the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan — must be accompanied by the intrusive “foreign agent” label. (Credit: Twitter / @meduzaproject)

Non-compliance with these rules can mean fines of up to 5 million rubles ($68,000). Repeated violations can lead to criminal charges and even imprisonment. Even other outlets who cite a “foreign agent” in their own stories can be fined if they don’t indicate their status.

As a result of these and other requirements, outlets designated as “foreign agents” have faced serious setbacks. Meduza, a well-known outlet that publishes in both Russian and English, has lost many of its advertisers and survives only thanks to a special fundraising campaign. Even so, it has reportedly been forced to cut its employee salaries by up to 50 percent.

Several other outlets have shut down outright. “We're a business publication, how will we exist without officials, without big business? We’re [now] naturally toxic for them,” said Alexander Gubsky, the co-founder of shuttered publication VTimes.

Which outlets have been declared “foreign agents” in Russia? Has anyone in the OCCRP network been affected?

The first outlets declared “foreign agents" were Voice of America, Radio Liberty, and a host of associated publications such as the TV channel Current Time. Other well-known targets include Meduza and The Insider.

Since December 2020, the list has included individuals as well. Among them are well-known human rights activist Lev Ponomarev and artist Daria Apakhonchich.

Roman Badanin, the founder of an outlet called The Project, which has partnered with OCCRP on several major investigations, is included. OCCRP’s Russian member center, Important Stories, as well as six of its individual journalists, are also on the list.

As of today, the list includes 47 entities, most added just this year. New additions have been made almost every week since July.

What about the “undesirable organization” designation?

This is a separate, even more restrictive designation. Organizations labeled “undesirable,” ostensibly on grounds of national security, are essentially banned from working in Russia.

Among them are major international development organizations like the Open Society Foundation, think tanks, foreign-based Russian opposition groups, and even academic institutions like Bard College.

Though this label can only be applied to “foreign or international” organizations, many independent Russian media outlets are registered abroad, leaving them vulnerable as well. The Project, registered in the United States, was declared undesirable earlier this year, prompting its head Badanin to leave Russia.

How have Russian journalists responded?

Some journalists have resorted to creative ways of highlighting the absurdity of the law.

Denis Kamalyagin, editor-in-chief of the designated newspaper Pskovskaya Guberniya, transferred money to several local officials by phone. In a report to the Ministry of Justice, he then listed them as having received funding from a “foreign agent” and suggested that they be required to label themselves as such.

On September 1, top editors from several Russian outlets sent President Putin a list of proposed amendments to the foreign agents law. In particular, they said, the designation should be done not by the Ministry of Justice but by a court. Other proposals include more clearly defining the term "political activity" and allowing up to 30 percent of an outlet’s funding to come from abroad without mandatory inclusion.

On September 8, marked in some countries as the International Day of Journalists’ Solidarity, many Russian outlets published banners reading "We’re Journalists, Not Foreign Agents" in support of their designated colleagues.