Natalia Andrade was among 270 people killed when a dam collapsed at a project run by mining giant Vale in Brazil’s southeast, sending a wave of mud and water sweeping through the nearby city of Brumadinho. Eleven bodies have still not been recovered.

“My sister Natalia worked in the Vale administration, [where she] started as an intern. We were proud to work at Vale,” said Angelica. “Everyone who was born and raised in Brumadinho dreamt of working for Vale.”

It was a dream for good reason: Vale is one of the largest miners on the planet, with operations in dozens of countries on five continents. In 2018 it generated US$36.5 billion in net revenues.

This story is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a collaboration started by OCCRP and Transparency International, and was reported with assistance from TI-Brazil.

In Vale’s home country of Brazil, many of its operations are in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais, which is home to 40 of the 100 largest mines in the country and where more than half of the country’s metal output is dug up.

But Vale has a deadly history in the state. In November 2015, another dam on a joint venture the company was running with BHP Billiton collapsed near the city of Mariana, killing 19 people and causing the biggest ecological disaster in Brazil's history.

Coming just over three years later, the tragedy in Brumadinho shook the country. Despite pledging it would never let a disaster like Mariana happen again, Vale is now facing several investigations by police, and both federal and state lawmakers.

A relative of a victim reacts during a ceremony to mark one year since the Brumadinho disaster on January 25, 2020. (Photo: Reuters/Cristiane Mattos)

A relative of a victim reacts during a ceremony to mark one year since the Brumadinho disaster on January 25, 2020. (Photo: Reuters/Cristiane Mattos)

It has also raised concerns about the possibility of future collapses. The latest survey by the National Mining Agency (NMA), a regulatory body for the industry, released in April, found that at least 24 of Vale’s dams in Brazil are not fully stable — 23 of them in Minas Gerais.

“We thought such a big company, with such big profits, would put employee safety first and comply with the law so that no life is lost. That is not what happened,” said Angelica Andrade.

“We saw from the investigation report that they could have prevented the breach and did not. They prioritized profit over the life of my sister and other people. And life is priceless.”

Josiane Melo also lost her sister, who was five months pregnant, in the disaster, along with eight colleagues from her job as a civil engineer for Vale. She only escaped because she was on the last day of a vacation when the dam broke.

“I wake up every day to fight. We cannot let Brumadinho fall into oblivion,” she said. “The families are the ones with the strongest will to fight because it hurts ... We deal with the pain every day.”

Risky Business

Three years before the Brumadinho disaster, Minas Gerais lawmakers voted to create a new body to streamline mining approvals called the Superintendence of Prioritized Projects (Suppri).

Suppri started work in January 2017 with the objective to “reduce bureaucracy and speed up the environmental licensing processes” for major projects, defined as ones that cost more than 50 million Brazilian reals (US$8.5 million, according to current exchange rates), or would create more than 250 jobs, or reduce social inequality.

A rescue team searches for victims killed by the collapse of the Brumadinho dam on February 5, 2019. (Photo: Reuters/Adriano Machado)

A rescue team searches for victims killed by the collapse of the Brumadinho dam on February 5, 2019. (Photo: Reuters/Adriano Machado)

It did just that. Suddenly complex applications, which previously would have gone through three stages of assessment involving hundreds of documents and sometimes expert consultants, only had to go through one.

Before, licenses for complex mining projects could take years to be approved. Through Suppri, according to Mariangélica de Almeida, an expert on Brazilian environmental law, they could be obtained in a few months.

The number of licenses issued every year by Minas Gerais increased from around 7,000 before the new process was instituted to 40,000 afterwards, according to the government’s own estimates. The average time spent assessing each license plunged from 51 days to under 10.

Data obtained under Freedom of Information laws shows Suppri analyzed 25 Vale applications between January 2017 and July 2019, including 21 considered “higher risk,” with ratings of five or six on a scale of one to six. It approved licenses for 19 of the 25.

One of the projects Suppri assessed was the Brumadinho dam.

OCCRP obtained a video showing the head of Suppri, civil servant Rodrigo Ribas, addressing the Mining Activities Chamber at a closed-door meeting in November 2018. He urges members of the chamber to downgrade the dam’s risk level, telling them “it was wrong” that the dam had been rated at a level six. The chamber acquiesced, moving Brumadinho out of the higher risk band.

Eight weeks later, the dam collapsed, killing 270 people. Official investigations are still ongoing, but experts say its structure was weakened when water started to leach into it.

A congressional report found Vale’s then-CEO, Fabio Schvartsman, got an anonymous email weeks before the disaster warning the company’s dams in the area were “at their limit.” Schvartsman, it said, “had full knowledge of the necessity of adopting urgent measures to increase the security of the dams.”

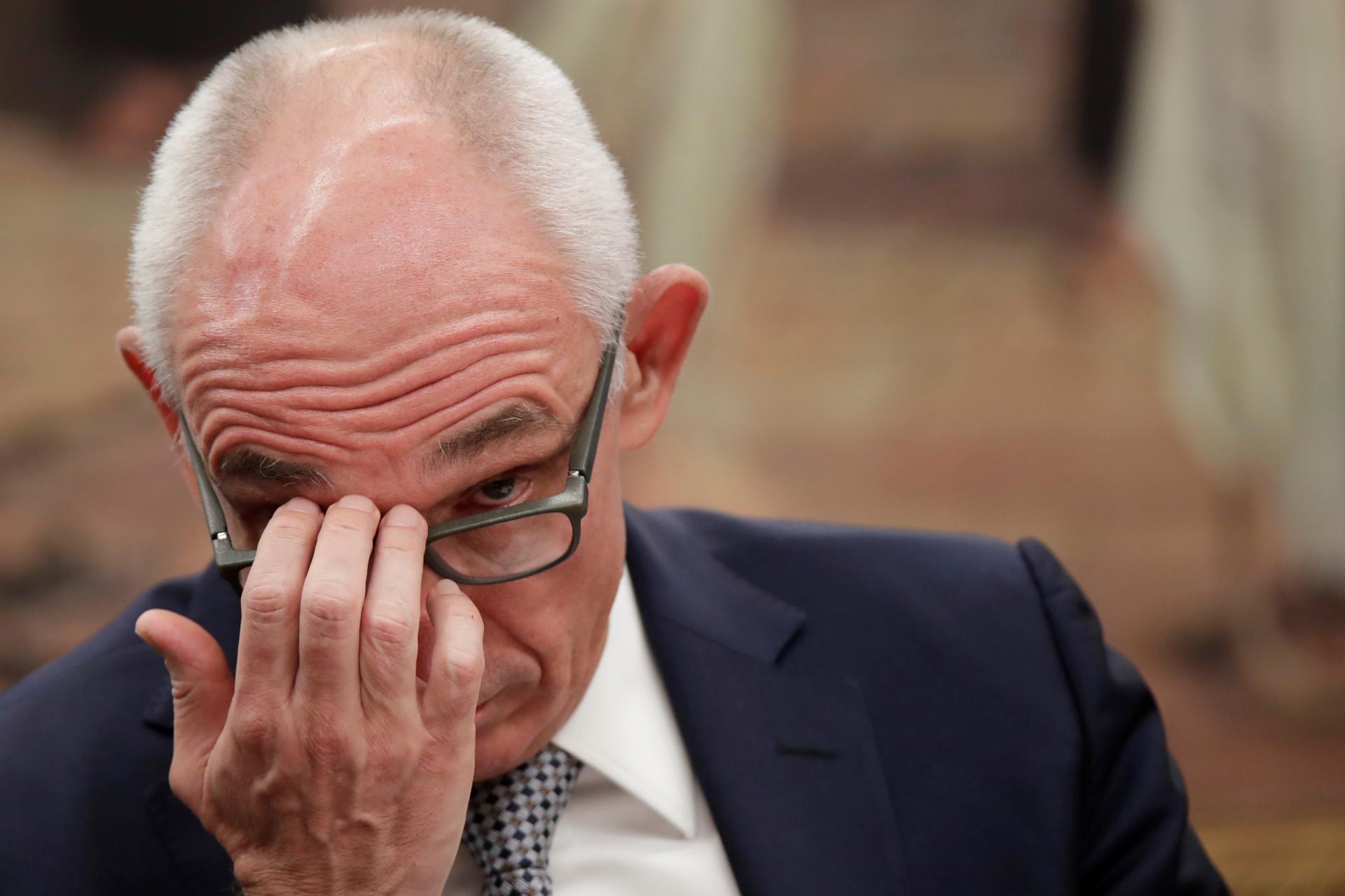

Vale S.A. CEO Fabio Schvartsman at a session of the external commission of Brumadinho at the Chamber of Deputies in Brasilia, in February 2019. (Photo: REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino)

Vale S.A. CEO Fabio Schvartsman at a session of the external commission of Brumadinho at the Chamber of Deputies in Brasilia, in February 2019. (Photo: REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino)

In January, Brazilian prosecutors charged 16 Vale executives with homicide. Prosecutors said they had known since at least November 2017 that the Brumadinho’s dam was at risk of failing.

Asked to comment on the decision to downgrade Brumadinho’s risk rating, the Minas Gerais government said the decision was based on technical assessments in accordance with the laws and regulations of the time.

Vale said the Brumadinho dam “met all the criteria” and safety regulations defined by law. In a statement, the company said the structure was checked several times by independent auditors and an inspection carried out two days before the disaster had found no issues.

The dam “was considered a safe structure by all Vale geotechnicians and the external companies responsible for auditing it,” Vale said.

Digging for Influence

Suppri was created by the administration of Minas Gerais Governor Fernando Pimentel, of the Workers Party, who held the post between 2015 and 2019.

Governor of Minas Gerais state Fernando Pimentel speaks at a news conference in 2015. (Photo: REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino)

Governor of Minas Gerais state Fernando Pimentel speaks at a news conference in 2015. (Photo: REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino)

Klemens Laschefski, a professor at the Institute of Geosciences at Minas Gerais Federal University who specializes in political ecology, said he believed Suppri was established to give mining companies more influence over government decisions.

Laschefski accused Suppri of giving priority in assessing companies that had made political contributions.

“There was no discussion about why these projects should be prioritized,” he said. “There is no technical justification for this. It's a scandal. There is no transparency at all. Suppri decides behind closed doors what the priority projects are and also decides how it can simplify environmental licensing.”

Pimentel received 1.5 million Brazilian reals (US$254,000 according to current rates) in donations from two companies owned by Vale, Vale Manganes and Vale Energia, in 2014, the last year private companies could donate to electoral campaigns in Brazil.

And he was not alone. According to official declarations of campaign funds from that year, 102 out of 130 politicians serving in the state or the federal parliament received donations from the mining industry.

The company logo of Brazilian mining company Vale SA at its headquarters in downtown Rio de Janeiro August 20, 2014. (Photo: REUTERS/Pilar Olivares/File Photo)

The company logo of Brazilian mining company Vale SA at its headquarters in downtown Rio de Janeiro August 20, 2014. (Photo: REUTERS/Pilar Olivares/File Photo)

In total, mining companies gave almost 15 million Brazilian reals to political campaigns in Minas Gerais in 2014 — the most of any state, according to an investigation led by the Brazilian newspaper Estadao.

Of those donations, 14.7 million reals (around $6 million) came from Vale. In total, the company spent 82.2 million reals ($33.6 million) on Brazil’s political campaigns that year.

“Campaign financing may have led to the creation of these structures captured in both the legislative and the executive [branches of government],” said Bruno Carazza, author of Money, Elections and Power: The Gears of the Brazilian Political System.

“If this happens via the capture of state agents in a way that takes into account only the interests of companies, to the detriment of the common good, that is a problem. This creates doubt.”

The Minas Gerais government said Suppri was an independent body that was free of political associations.

“Suppri was created by the Assembly Minas Gerais State Legislature after a broad debate with society,” it said in a statement. ”The Secretariat's actions are not based on political motivations.”

Vale said all its electoral donations “were made in full compliance with the criteria of the legislation in force at the time and were regularly reported to the Electoral Court.”

A lawyer representing Pimentel did not respond to a request for comment.

‘A Labor Crime’

Today, 12 of the 19 Vale projects approved by Suppri in Minas Gerais have been stopped, either halted by authorities or by the company itself due to concerns about the dams.

They include the Cava da Divisa project, a vast iron-ore mine that was expected to cover 800 hectares, produce 15 million tons a year. and run until 2040. Suppri approved a license for the project in November 2018, giving the Cava Divisa dam a level six rating, and work started as early as 2019.

In February 2019, Vale started evacuating people from the area due to concerns about a dam on the project called Sul Superior. Then in October 2019, the NMA warned the dam, which was holding back some 5 million cubic meters of tailings, was “an imminent risk.”

In the Nova Lima municipality, the NMA also stopped the development of the Vargem Grande Complex. Suppri granted the project a license, but work was halted in February 2019 after stability risks emerged. About 50 families had to leave the area.

After asking for certification that the dam was safe, the NMA said in October 2019 that the project “did not demonstrate stability.”

Suppri said in response to questions from OCCRP that the Cava da Divisa expansion was rated before issues were raised about the stability of the nearby Brucutu Mine, which impacted the dam. Overall, it said, the body follows the same technical and legal criteria as other regional environmental regulatory bodies.

“Suppri does not participate in decision-making regarding the definition of the priority of the processes sent for analysis by it,” it said. “There are no differences in the forms of analysis or judgment powers of the processes analyzed by Suppri in relation to the other Suprams [regional environmental offices].”

At the time of publishing, Vale had 12 new applications before Suppri.

People march to Brumadinho city, as they protest against the Brazilian mining company Vale SA, in Belo Horizonte, Brazil January 20, 2020. (Photo: REUTERS/Washington Alves)

People march to Brumadinho city, as they protest against the Brazilian mining company Vale SA, in Belo Horizonte, Brazil January 20, 2020. (Photo: REUTERS/Washington Alves)

For the people of Brumadinho, however, the damage has been done.

Vale has reached an agreement with Brazil’s Labor Prosecutor to pay spouses, children, and parents who lost relatives in the tragedy R$700,000 ($118,000) individually. The company is still under criminal investigation, while former CEO Schvartsman was charged with homicide.

But some locals, including Juliana Fonseca, want more to be done. She moved to Córrego do Feijão, where the dam was located, in 2005 and has worked there as a schoolteacher ever since. Several of her students died when their community was flooded with a torrent of mud.

She is a leader of the Affected Families Commission, which is lobbying for criminal charges to be brought against Vale over the collapse of the Brumadinho dam. On the 25th of every month, they meet to remember the people killed in the disaster.

“My husband lost his sister, my stepdaughters, and four cousins. We lost a lot of family, friends, colleagues,” she said. “In Vale's view, reparations are indemnities. They think that because they paid, it's settled. But we do not see it that way.

“Compensation is necessary because [our] family members died working. It was a labor crime; Vale was aware of what was happening. In addition to the financial compensation, we want punishment for those responsible.”