With fingers on the triggers, they moved down narrow streets, broke into homes, basements, and shacks, and pulled sleeping men out of their beds.

By sunrise, 116 alleged members of the ‘Ndrangheta – one of the world’s most powerful crime syndicates – were under arrest, including the bosses of some of its most important clans.

“Mandamento,” a long-planned operation aimed at crushing one of the world’s most dangerous criminal groups, had ended with a big catch. It also helped investigators piece together, with more detail than ever before, how the group operates.

The Calabria-based ‘Ndrangheta stretches its tentacles throughout Europe. Italian prosecutor Nicola Gratteri, who wrote an authoritative book on the cocaine trade, believes that the syndicate controls over 40 percent of the world’s market of the drug.

Experts say that in 2013, it made more money than Deutsche Bank and McDonald's put together, with a turnover of €53 billion (US$ 70.41 billion), mostly from drug trafficking.

These huge profits are, for the most part, safely invested in off-shore accounts. But the organization’s soul still rests on the sun-dried hills of southern Italy. This is where all the important decisions are made.

Over the decades, the old farmlands of Calabria have turned into a network of tiny towns and villages, connected by country roads that cross barren fields, dotted with the concrete skeletons of unfinished houses. It is one of Italy’s poorest regions.

The Calabrian town of Staiti. (Photo: Jacopo Wether, CC-BY 4.0)

The Calabrian town of Staiti. (Photo: Jacopo Wether, CC-BY 4.0)

In the towns, among the shops and government buildings, there are always at least a couple of places, normally bars, where one can find a middle-ranked clan member who is in charge of the street. He’s the one to whom residents can complain about their problems.

And from the little tables on the verandas to the most secret bunkers where the top bosses hold court, the flow of information is constant.

The investigation that led to operation “Mandamento” - led by local anti-mafia prosecutors and the Carabinieri - went on for years. Detectives pieced together clues from dozens of previous anti-mafia operations and put them together like a jigsaw puzzle.

The picture still has a few missing parts. But it already reveals a state-like criminal structure that has developed here over centuries.

A 3,000-page-long indictment that includes transcripts of tapped conversations, confiscated documents, and other sources reveals who is who in this parallel society and how it works.

Just like a federal state, the ‘Ndrangheta is divided into territorial units, and its structure rests on its own legislative, executive, and judicial pillars.

As was discovered during operation "Crimine," that resulted in the 2010 arrest of 305 suspects, a single council -- the “Provincia” -- rules over the whole syndicate.

The Provincia exercises influence over the whole region, and the whole world as well. Calabria itself is divided into three smaller territorial units, known as the ‘Mandamenti: the Mandamento Tirrenico, the Mandamento Ionico, and the Reggino (from the city of Reggio Calabria).

Of these, it is the Ionian side of Italy -- the “sole of the shoe” -- that has been home to the most prominent ‘Ndrangheta families. This area has the religious sanctuaries that its members especially revere.

Each town within ’Ndrangheta territory contains a “Locale” - а basic administrative unit ruled by a boss, the Capo Locale, through his own chain of command.

The titles of his subordinates are not just there to sound fancy. Each is linked to a specific function.

A Capo-Crimine is something like a minister of war, while a Contabile acts as a treasurer.

“Thanks to this level of organization, there is very little money spent in Calabria that doesn’t fall under ‘Ndrangheta control,” Claudio Cordova, director of the regional online newspaper Il Dispaccio, told OCCRP.

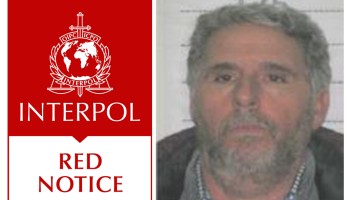

“The state is me,” boasts Rocco Morabito in a wiretapped conversation released by police.

A still shot from a police surveillance video shows 'Ndragheta members walking together. The superimposed wiretrap transcript quotes Rocco Morabito: "The state is me, Pe! Check it! The Mafia! The original Mafia, though, not the shoddy one." (Video credit: Arma dei Carabinieri)

A still shot from a police surveillance video shows 'Ndragheta members walking together. The superimposed wiretrap transcript quotes Rocco Morabito: "The state is me, Pe! Check it! The Mafia! The original Mafia, though, not the shoddy one." (Video credit: Arma dei Carabinieri)

Rocco, the son of one of the most important ‘Ndrangheta bosses, the already jailed Giuseppe “u tiradrittu” (“shootstraight”) Morabito, was among the 116 arrested in the beginning of July.

The family rules over the small Calabrian town of Africo, but also manages more distant Locali in Rome, Turin and Milan. It even has an extensive presence in Germany.

The Morabitos were the keystone of the ‘Ndrangheta’s early alliances with the Sicilian mafia, and their construction companies have obtained all public contracts in the Africo area since the 80s.

In the early 90s, the Morabito family was found to be one of the most powerful clans involved in international drugs and weapons trafficking. Giuseppe Morabito was considered the most iconic and feared man of the ‘Ndrangheta.

But as powerful as it was -- or still is -- the Morabito is only one of the 24 clans that were targeted by the overnight police operation.

Not only has the latest investigation led to a record number of arrested bosses, but it revealed structures and titles police had never heard of.

While some have been decrypted -- such as the “Corona” (Crown), which seems to be an alliance of five or more small Locali that join together to gain more weight in the Provincia -- investigators still have not figured out what the “Cavaliere di Cristo" (knight of Christ), “Crociata” (Crusade), or “Stella” (Star) are.

Whatever they may be, it all seems to be working so well that almost nothing gets done in Calabria without the ‘Ndrangheta.

Previous investigations, as well as arrest and confiscation orders, show the syndicate’s clans have been involved in many major regional development projects – from highways and ports to tourist resorts.

The port in Gioia Tauro was built in the mid-90s and has since grown into one of the largest in the Mediterranean. And in a February 2008 report, the parliamentary Antimafia Commission concluded that it belonged to the mob. The ‘Ndrangheta “controls or influences a large part of the economic activity around the port and uses the facility as a base for illegal trafficking,” the report read.

When the ‘Ndrangheta gets involved, it means business. All of a project’s sub-contractors, its relationship with local institutions, and even the hiring of workers is influenced by the syndicate.

“It effectively eliminated legitimate competition from companies not influenced or controlled by the mafia in providing goods and services, performing construction work and hiring personnel,” the Antimafia Commission concluded.

Needless to say, the group’s influence has a pernicious effect on the struggling Calabrian economy. “The ‘Ndrangheta is a parasite,” Roberto di Palma, a judge who presided over two corruption trials related to a regional highway, told the New York Times.

Some of the organization’s money is invested in tourism. In October 2006, police confiscated a 450-million-euro residence complex called ”Gioiello del Mare” (Jewel of the Sea), built in the town of Brancaleone and presumed to be a huge money laundering operation.

The ‘Ndrangheta’s level of control over all activities in the region is "hard to believe,” Chief prosecutor of Reggio Calabria, Federico Cafiero de Raho, said.

Even when a “clean” company wins a bid, the syndicate uses intimidation and even violence to extort a 10 percent cut of the profits.

‘Ndrangheta-owned companies infiltrate the sub-contractors and force them to rent their machines, Cafiero de Raho said. Entrepreneurs who resist are kidnapped and brought to the “boss.”

Apart from the syndicate’s structure and its business methods, investigators also managed for the first time to understand the ‘Ndrangheta’s judicial system – and it’s not exactly as Hollywood likes to portray it.

The process is a little more complex than just “Don Corleone” issuing a death penalty.

When the organization needs to rule on a member’s loyalty or to judge somebody’s behavior, a court - known as the “Tribunali di umilta” or “Tribunal of Humility” - is assembled.

The Capo Locale acts as “judge,” the Capo Crimine becomes the "prosecutor,” and a friend of the suspect takes on the role of the defense lawyer, known as the "carita" ("charity").

Such tribunals settle quarrels among the clans and try members suspected of having violated the ‘Ndrangheta’s code of conduct.

The punishments can be harsh, particularly if the guilty party has violated the code of silence - the infamous “omerta” - designed to protect the organization from the authorities.

But members can also be tried for harassing female relatives of other mobsters, for failing to sufficiently punish another member, or for disobeying a leader’s orders.

These tribunals apparently use rituals dating back to the end of the 19th century, and have been known to police since the end of the 60s.

But it was during the “Mandamento” investigation that the details of their mechanisms came to light for the first time.

The mildest crimes are called “trascuranze,” or “neglects.” More serious transgressions against the syndicate are called “tragedie.”

Those include the so-called “macchie d’onore,” or “stain on honor.” This means the defendant has destroyed his credibility and will be kicked out of the organization.

This can be worse than it sounds.

“It is unlikely for an ex-’Ndrangheta member who has been discharged to keep living,” said Antonio Zagari, an ex-affiliate who is now collaborating with police.

The sentences for other “tragedies” show that Hollywood’s image of the mob isn’t so far from the truth.

Blaming someone else for your own crimes, inciting wars between clans or – worst of all – speaking with police (known as ”infamita” or “betrayal”) can carry an outright death penalty.

During the course of the investigation, other syndicate rules were found in a notebook in the house of an arrested member - and they provide a tantalizing glimpse into how the group indoctrinates new members.

The most basic rules are presented in the form of a highly ritualized dialogue.

“What did the society [the ‘Ndrangheta] give you?” asks the first line.

“The Society has given me seven nice things,” goes the answer.

“Humility to be humble with my companions.

Loyalty to be faithful to my companions.

Politics on how to speak with my companions.

False Politics to use with cops and unworthies to save our honor.

A knife to protect me and the whole Society.

A mirror to look behind my back, and

A razor to scourge the infamous and the unworthy.”

The “Mandamento” operation was a “blow to the heart of the 'Ndrangheta," said the president of Italy’s Anti-Mafia Commission, Rosy Bindi.

"They were hit,” she said, calling the operation a success that would end the alleged impunity of the mobsters and deny their claim to be the true authorities in Calabria.

“The state is there and does its part in the fight against lawlessness,” she said.

The operation also sends a message to the “honest Calabria that does not bow to the intimidations of 'Ndranghetists," she added.

By arresting a whole generation of mob bosses on July 4, Italian authorities appear to have won an important battle.

But have they won the war?

The ‘Ndrangheta is more than just a criminal organization, experts say. It’s a way of life.

Calabrian folk songs, known as “maravita,” promote the traditional values of Italy’s south. Among other topics, they tell stories of men threatened with death for speaking to the police, hailing as heroes those ready to go to jail rather than betray their clan.

“The cultural aspects of the consent around mafias is born of a long history, not from a predisposition of the populations involved,” writes Enzo Ciconte, a historian, teacher, and politician, in his book, “Atlas of the Mafia.” “And mafias are able to renew and regenerate the initial consensus."

In a conversation secretly recorded by investigators, a young girl reads her mother a letter she had gotten from a classmate.

The 15 year-old boy addressed it to the girl’s father - a mobster currently in jail. He hoped the daughter would find a way to deliver it to him.

“Good morning, how is it going? I hope everything is alright,” the boy wrote.

“I want to put myself at the disposal of you and your family."